One Acre Wonders – Outdoor Schooling, Autism Support, and Equine Wisdom with Catherine Ward & Nicole Jones | Ep 30 Equine Assisted World

Rupert Isaacson: Welcome

to Equine Assisted World.

I'm your host, Rupert Isaacson,

New York Times best selling

author of The Horse Boy, The Long

Ride Home, and The Healing Land.

Before I jump in with today's

guest, I just want to say a huge

thank you to you, our audience,

for helping to make this happen.

I have a request.

If you like what we do, please

like, subscribe, tell a friend.

It really helps us get this work done.

As you might know from my

books, I'm an autism dad.

And over the last 20 years,

we've developed several

equine assisted, neuroscience

backed certification programs.

If you'd like to find out more

about them, go to newtrailslearning.

com.

So without further ado,

let's meet today's guest.

Welcome back to Equine Assisted World.

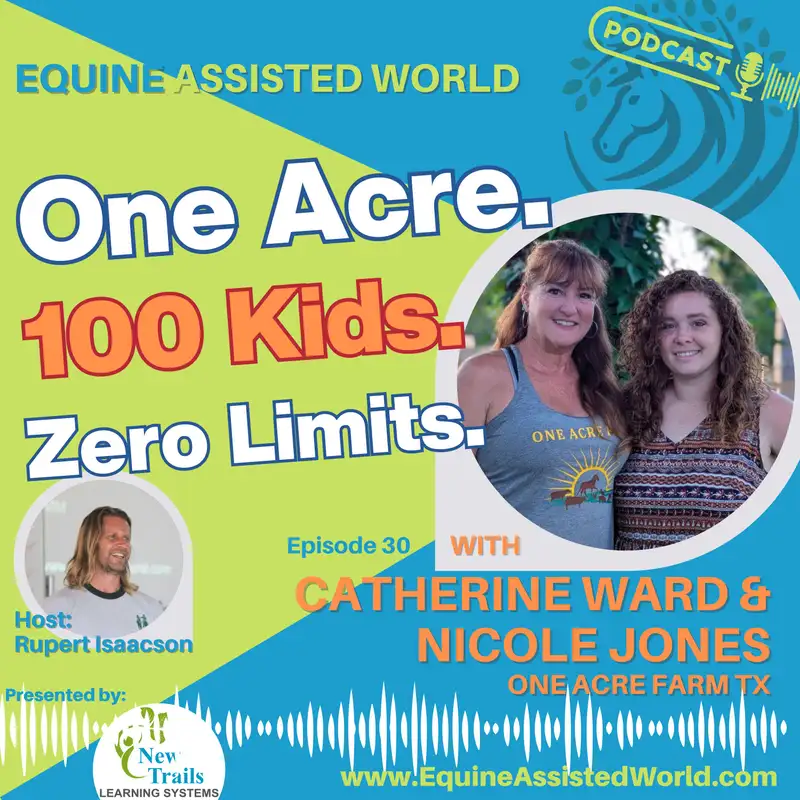

With me today, . I've got Catherine

Ward and her daughter, Nicole Jones,

who together run a pioneering place

in Houston, Texas called One Acre Farm

where they do all kinds of miracles.

So the reason why I want them on the

show is a lot of us think of equine

assisted stuff happening in large rural

areas where we have a lot of space.

One acre farm is just that, and it's

within the city limits of Houston,

and it's a bit of a groundbreaking

concept and it shows what really

can be done with very little.

So any of you think, well,

I haven't got enough space.

You kind of need to hear a little bit

how Catherine and Nicole maximize what

they've got and achieve results that are

frankly, quite breathtaking with kids.

So welcome to the show.

Catherine and Nicole, please tell

us who you are and what you do.

Catherine Ward: Hey, Robert,

thank you for having us.

We're, we're quite honored

and excited to be with you.

I'm Catherine Ward.

We live about 35 miles

north of Houston in Porter.

I own and run one acre farm.

And it started probably in 1999.

Our very first class was how to

Raise Chickens in Your Backyard.

Because of our location where we are

while we're kind of rural, we're set in a

very urban or very suburbanite type area.

And so there are a lot of, a lot of women

that live in neighborhoods that wanna have

four or five chickens in their backyard.

And so that was our, our goal to

kind of kind of get started there.

Then we started classes for Homeschoolers

and Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts.

And then fast forward to from 1999

to 2016 when we met you and then

got our certification in Horse

Boy Method and Movement Method and

added that to all of our programs.

And then fast forward to 2021 and

we opened an outdoor farm school.

And so now with all of the programs

that we have from kids aren't in

play, our Sensory Saturday, our

private autism sessions and our

elementary farm school and our early

childhood farm school, we service

about a hundred to 150 kids a month.

Rupert Isaacson: Impressive.

Thanks.

Okay.

Nicole, who are you?

Yeah.

In this

Nicole Jones: so I'm obviously

a daughter of Catherine.

I'm a mom of two and my two kids come

with me to the farm school that we run.

I was a horsey kid.

I was homeschooled all the way through.

So, I was homeschooled on a farm.

Very similar to how a lot of the

kids that we work with today are

being schooled and had a lot of

interaction with animals growing up.

A lot of autonomy to my day.

A lot of movement involved in my

homeschooling and education growing up.

And so currently I am the early

childhood teacher at this school.

And then also Catherine.

I co-create curriculum together

for things that we're doing on

the farm and for other people who

are interested in, in curriculum.

But a lot of what got us, or at least

got me to where we are with the school

now was the homeschooling background.

A lot of the horsey stuff growing up.

And then I was also an a, b, a

therapist early on in my, teaching

days I wanted to become a teacher.

I got into a BA therapy but very quickly

realized it didn't sit right with me.

I was there for about two years and just

felt like there was something missing.

I, I loved getting to have the

relationship with children and

being able to be one-on-one with

kids and grow that relationship.

But being a 19, 20, 20 1-year-old

teacher, I was just still not knowing

much and not being in the field very long.

It just wasn't sitting right with my

spirit, the things that I was being

told to do, and feeling like the,

the happiness of the children and the

joy of early childhood education was

just taken out of what we were doing.

And it all was very clinical.

It, it didn't have this while we were

building a relationship with kids.

It just didn't have that, that.

Fun aspect you would expect.

And you know, we, I was working with

children who were nonverbal who were poop

smears, eating their poop all the way,

you know, that might be a morning student.

And then an after Stu afternoon

student was someone who could read

and write and talking verbally.

And so putting those two kids in

the same class together, it was

just, there was a lot of disconnect.

And didn't, although I was working

for a very highly regarded a BA

clinic, I just felt like it just,

it wasn't sitting right with me.

And so not too long in the field

and just feeling like this isn't

right, I need to find something else.

I found Montessori education

very happenstance, and so I was

completing my college observation

time in different, you have to go to

different schools and observe classes.

And so I picked a Montessori school to

go see 'cause I just never heard of,

heard of it and wanted to see what it

was about and walked in and was just, in

10 minutes I was like, this, this is it.

This was the thing.

It was so similar to how I was

homeschooled as far as the kids

could walk around the class and

pick things they wanted to do.

There was interest led learning.

They could move around,

they could go outdoors.

They had this open space to their

day of, all right, I can pick

and choose what I want to do.

And the teachers would pop in and out as

they were needed and help direct the kids.

But it was, they had so much autonomy

to what they were able to do.

So, that night I went home, decided I

was gonna get training in Montessori.

I got certified the very next year.

I went through my one year

internship and 500 training hours

or whatever, and got that done.

And then went into Montessori education.

A couple years into that is when Catherine

and I went to temple Grandin's speech

and found you and then added this whole,

whole other aspect added to, oh my gosh.

Here's where, you know, while Montessori

education was originally based in

helping kids with special needs, there's

this whole other aspect of the science

I didn't understand, and that Dr.

Montessori was also trying to

understand and, you know, the neuro

neuro pathways that are formed

and all of that with movement.

Anyway, so we had all that added to

it, and then COVID happened, you know,

we were doing some, we were doing

some sessions with families, but then

COVID happened and a lot changed with

everybody, and Catherine and I decided

you know, this might be the time we want

to start something at one acre farm.

And we did that.

So I left my Montessori teaching job.

We went into this together and

it's been really great since then.

We just, we just keep on trucking.

Right.

So you,

Rupert Isaacson: you started Nicole

with special ed and as in America, as we

know, a lot of people are funneled into

applied behavioral analysis, A, b, A, and.

You know, like many of us,

you found it restrictive.

Catherine Ward: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Coercive not joyful.

Then you found Montessori which

is much closer in line with the

autonomy you've used that word.

I want to return to that word.

And why is autonomy important that you'd

experience, you know, homeschooling

or being homeschooled in nature?

It's interesting that you were

homeschooled because you know,

Catherine, you have been a teacher

in the regular school system, right?

Yes.

So can you talk us a little bit

through your background and career?

How did you as a regular

teacher then decide, well,

actually I want to homeschool.

And then how have you brought those

two things together into one acre farm

where you do have a school structure,

but of course you're now using I.

Montessori movement method and other

modalities, you know, altogether.

Can you just talk us through

that trajectory, please?

Catherine Ward: Sure.

I could, let me go back a little bit.

So I was born in Texas,

but raised in Louisiana.

My mom remarried when I was very young,

and it was a very unique upbringing

because my, my father, my stepfather

was one of the richest men in town.

So we lived in a huge mansion, but in

our back acreage was all this livestock.

So I was kind of raised in

a farm, like farm lifestyle.

I was also given that word

a lot of autonomy with being

able to take care of animals.

And my mom was very down to earth

and even though we lived such a

lavish life or we had access to that

kind of wealth she raised me in a

very down to earth type mentality.

So I'm very grateful for that.

So that I think came to play

later in life also, which, we'll,

we'll see the interconnection.

So then I came back to Texas in

1987 and then started college.

Well, I take that back.

When I was in New Orleans, I had.

I started college and my

first major was psychology.

No, my first major was marine biology,

and then I changed to psychology

and then I changed to pre-med, so

I wanted to go into medical school.

And then we moved to Texas.

I finished all of my pre-med and

got accepted into UTMB of Galveston

under their physical therapy program.

And they had only had out of, you

know how many hundreds of applicants.

Only 30 were accepted.

And so I was accepted and right

then before deciding to go to

medical school, I changed my major

again and went into education.

And so I had to start my college

pretty much all over again.

Went into education and graduated in

early childhood or with elementary

pre-K to eighth, early childhood

and reading specialization and

and my love of farm animals and

teaching just kind of combined.

So when I was married, we had a little

bit of acreage and then Nicole was

born to me and then her sister Kristen.

And it was even with my

public school teaching.

So after graduation, I did teach in the

public school system for a few years.

I taught kindergarten,

first grade and third grade.

And then once I had children, I thought,

oh my gosh, I don't wanna be away from

them and I know what the system is like,

and I know that they are gonna be in this

white room for eight hours that I was in.

And so it became a philosophical and

somewhat of a faith decision because I

also felt like, eight hours away from us.

That I, I wanted that influence

on them spiritually and in their

faith and in their philosophy.

So the decision to homeschool was made.

I left teaching and then I, we

homeschooled the girls their

whole career for homeschooling.

And, and as Nicole referred to,

it was a very relaxed atmosphere.

We spent hours and hours outside and

it was kind of naturally within me

to wanna follow their interest and

follow what they were interested in.

And, oh, I'm so, I have

so many squirrel moments.

It's like, oh, look, there's a bug.

Let's go look at that bug.

So we, their, their

homeschooling was very casual.

Of course, we had some regimented

things like, you have to learn math.

But for the most part because both of the

girls were interested in horses, I made

sure that they could get horse lessons.

And so while we couldn't afford

those types of things being on

one income we traded our work.

So we would go and muck stalls.

I think one of the places we went had

like 23 stalls, and we would go every

day and muck in the morning, 23 stalls

so that my girls could have lessons.

And then we borrowed horses from

other people so that they could

then learn how to ride barrels.

And we were very fortunate

that other people were willing

to work with us like that.

So both of the girls were, were able to

follow their, their interest with horses.

Rupert Isaacson: So you are, you

are there homeschooling, you are

trading your work for writing lessons.

You are doing it somewhat faith-based,

but also because you just don't

want to be away from them.

I've got a question, which is that

you, you, you mentioned having grown

up very wealthy, but then you are now

a one income family where you need to

trade mucking out for horse lessons.

If you're a listener, you

go, Ooh, what happened there?

What happened in that story?

Where'd the money go?

And how come you didn't sort of end up

with that entitled attitude that you might

have ended up with, you know, growing

up with, with, with money when the time

came that you didn't have money anymore?

Talk.

Talk us through those.

What's the missing bit of that story?

Catherine Ward: So, I mean, the

first loss of money was when my mom

subsequently divorced my stepfather.

And so then there, that family unit was

no, no longer connected in that split.

They did split the business.

They had several businesses.

We had car dealerships.

They built homes.

They had a boat shop.

He was into real estate, so there were

all kinds of things within the, the many

different cookie jars that were in there.

And so, my mom had to start off as a

single mom with myself and my sister.

And so she, in the divorce, she

took over one of the boat shops.

And over the next few years, she

became one of the most renowned

boat dealers in the United States

because she was a woman and she grew

that one business into three more.

So she took it from one location to two

more locations and and kind of became

a millionaire in her own right Then.

During that time, very sadly

my sister was killed in, in an

airplane crash, a private airplane.

And that, that completely changed

our family completely overnight.

To watch my mother grieve.

So deeply.

And then to watch my, my grandparents

in their own grief, but then having

to help support her and support me.

And you know, when you look at

your life as a timeline, my whole

life until the birth of my two

daughters, my life always had that.in

my timeline is that was the

anchor of my life before my sister

died and after my sister died.

And, and again, until Nicole and Kristen

were born, that's how I measured my life.

And, and it did forever change us.

And it forever changed our outlook

as a family and our connection.

During that time with my mom having

a boat shop or a boat dealership?

There were a few there were a

couple of of injuries that happened.

You know, like when you go to a

boat show that's in a huge arena

someone tripped and fell and cut

themself and of course sued her.

And then there were some other injuries.

And so those lawsuits just totally

demolished the business, right.

It, it just destroyed the business.

So we lost money.

Then she got out of the business and

decided to go into real estate and then

she made herself a millionaire again.

And and during that time, a lot of

people and friends wanted her to co-sign

for their own businesses and she did.

She was very generous.

And and then those would flop

and so she lost all of it again.

And then that was when we

decided in 1987, you know what,

I'm gonna go back to my roots.

My mom was, would say this,

I'm gonna go back to my roots.

Let's go back to Texas and

I'll go back to teaching.

'cause she had been a

school teacher before.

So we came back to Texas and

she went back to teaching.

And then that's when I was entering

college shortly after that.

Rupert Isaacson: Got

Catherine Ward: it.

And then, and then the lifestyle was just

a very middle s middle class lifestyle.

And then when I got married, the

same thing, just middle class.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

You, you mentioned I mean, it, it's very

interesting 'cause it gives you multiple

perspectives on life, you know, to go

from growing up wealthy to losing it all.

To intense grief to having, to

making it again, to seeing a business

how business can be destroyed.

You know, and this is something which

I think, you know, a lot of business

owners in America live justifiably in

fear of that day that somebody sues

you know, business friendly country,

but also business friendly for lawyers.

Sadly, you know, it, it, it can

wipe people out, but it certainly,

I think, gives you an interesting

place of empathy where you can say,

well, no matter who you're dealing

with, I've, I've lived that lifestyle.

And at the end of the day,

I know what's important.

You talk about faith-based, obviously

for my non-American listeners, you know,

when you're listening from a European

perspective and you hear about, you

know, Christian homeschooling, one

thinks of, you know, armed compounds

in the woods and you know, ex extremism

basically, and people being you know,

homeschooled so that they won't learn

about Darwin and that sort of thing.

But your way of teaching at one

acre farm is in no way like that.

So when you talk about faith

I'd just like you to, to talk

about how, how you guys consider

yourselves Christians and how that.

Works in an interplay, not just

with science teaching, but also

with, you know, what values are.

You know?

Because again, many of us in, in

Europe, we have a, a fear of religious

extremism because all our history

is learning about religious wars and

witch burnings and things like that.

I'm like, well, we don't wanna

go back there and we don't

want that kind of extremism.

We sometimes see that coming

out of the USAA little bit.

But knowing you as ideal, I

know that's not you guys at all.

So talk to me a little bit about how you

weave your, your faith into what you do.

'cause I think it's, it's, it's,

it's, it's useful for us on the

European perspective to consider this.

Catherine Ward: I, I think for me, I've

gone through some transformations through

the years and I would say that there was

a time that I was very tunnel visioned in

that my philosophy was the only philosophy

and, and or, or that the tenets of it are

a hundred percent the only way to think.

But then ironically, as I got exposed

to the world, it was actually an

aha moment when I was at your ranch

in Elgin at a training for Movement

Method and Horse Boy, where I met all

these people from all over the world.

Here at the ranch and we were all

learning Movement Method and Horse Boy

and, and I had gone there with such.

A thought process that, that I was,

I had already prejudged all these

people before I had ever even met them.

And I was now surrounded by people

that were so highly intelligent and all

had their own philosophies or faith.

But the, the common thing

that I saw was kindness.

Kindness and unconditional love,

which are the tenets of Christianity.

But I saw them, I saw it in people

that I would've never pinpointed as

being the evangelical Christian type

of western Christian that we have.

And that opened my mind to wow, there

is, to me, it became a universal

truth in my heart, that kindness

is of the utmost importance.

And so I came away from that

and I started to do studies on

ancient religions and stuff.

And, and I found that through some of

the, the, the basic first religions and

even Native American, that the common

tenant through all of that one is that

they all believe there is a creator of

whatever, whoever that creator is, at

least they acknowledge there's a creator.

And then second to that was just

kindness and unconditional love.

And that I feel like every day when I

wake up, that is what drives me every

day is to just to be kind to people.

And and I believe that as I see my

daughters, both of them as adults,

that they have such huge, kind

and compassionate and empathic.

Empathetic hearts.

I'm, I'm just very proud of

them for, for being that way.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

It's, you know, I think what often gets

lost in, in religion is spirituality,

you know, because of course, as soon as

you, you have a, a church or a temple or

whatever one wants to call it, usually

have a bloke, you know, standing there

with a jar that you can put your money

in and it sort of goes from there.

Whereas of course, yes, one's

relationship with the divine is one's

relationship with the divine and.

If there's a Christ message

out there, I think as you say,

it's, it's love by neighbor.

Catherine Ward: Well, you had asked how

we deal with that today at, at the school.

Yeah.

Yeah.

And so, we're not, we're

not a faith-based school.

We don't advertise ourselves as such.

And, and I think that was a decision that

Nicole and I made from the very beginning.

Mm-hmm.

That we did not want that, that,

not that we were turning our back

on anything, but that that is not

what we wanted as defining us.

And that we wanted to have an eclectic

group of people and kids because we wanted

the, like-mindedness to be what is the

goal of those parents for their children.

And we wanted, and those people

can come from all walks of life

if the goal for their child is to

be outdoors and to be free from

institutionalized type classroom.

And so we made that very conscious

decision to not advertise

ourselves as faith-based because

believe me, in this area I.

Where we are.

It, it, it could have

flourished even that way.

But how I speak with, with our

kids, 'cause I'm the teacher of

the elementary ages seven to 10.

And, and so we really delve

deep in our subject matter

is all of a animal husbandry.

So like, let's say we're talking about

chickens, we're gonna do the parts

of the body, the digestive system,

reproductive system where did they

originate, how did they migrate?

And so we interconnect geography

and history and all of the

subjects but studying chickens.

And we'll talk about DNA and we talk and

especially in the reproductive system.

And, and then a lot of times I'll, I'll.

Tell the kids, there are two

basic ways to look at the world.

You have one, one belief system

that believes that everything

was created by a creator.

And then you have another that

believes that everything was

happenstance through evolution.

But, and I tell 'em this is not

where we discuss or debate that what

I want y'all is I want y'all to see

how they can both be interconnected.

There are, there is science that

supports both, and we are going to stay

open-minded and look at the development

of chickens or goats or whatever from

that perspective and see that there's

probably bits of truth in both of it.

And, and I want them to kind of just

become their own independent thinkers.

And the parents have always

been very supportive and very

appreciative that we approach science

in, in that way with the kids.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

I mean, you talk about the need to,

this word autonomy has come up and

of course autonomy is an intellectual

process as well as deciding what I

want to do from moment to moment.

Nicole, why do you feel autonomy

is so important in the development

of, of a human talk, talk,

talk, talk to us about this.

Nicole Jones: I think this goes back to

as I was writing some things down as my

mom was speaking, because her and I, I,

it's been a while since we've talked about

this subject, so I think this is good.

I agree with a, a main goal of mine is to

let kids be able to think for themselves

because the, the systems that we put

them through, tell them how to think,

tell them what to do, tell them when

to do it, and then they come out of the

system and they don't know what to do.

They don't know how to start a business.

They don't know how to balance

their, their bank accounts.

They don't know how to take care of

animals that like these basic human.

Just everyday requirements that we

have as, as adults that my friends at

30 still don't know how to do because

they went through the public school.

Like just those things that if you

don't know how to do something, that

you can go and figure out how to do it.

So having that self-directed autonomy

that homeschooling gives you, that farm

schooling, gives you that movement method.

Those types of based

educational methods give you it.

It doesn't matter what walk in life

you're going to do, if you want

to change careers or if you, you.

Decide to take a left turn somewhere.

If you have those skills in, okay, I can

do this and figure it out because I've

had the autonomy and the practice of I

want to start lemonade stand, or I want

to figure out how I can afford to keep

a horse for the year, you know, those

kinds of things then you're gonna be able

to succeed in, in just about anything.

And I think it's important to

start that very, very young.

I teach the kids ages four to seven

and these little four year olds, and

sometimes we have three year olds

they're feeding the animals themselves.

They come and tell us like, that

animal's poop looks different

today than it did yesterday.

Or do we need to check

and make sure it's sick?

Like, just those observational things

that we have lost being out of nature.

And so being, basically being able to,

to allow kids to think for themselves

and be those independent thinkers and

autonomy with your day gives you that.

And it doesn't mean that we just

let kids go and run around and

do whatever they want to do.

You know, there's a boundary to, okay,

you wanna throw mud, that's fine.

You can't throw it at other kids, but

you can go throw mud at the fence and

you can figure out how far you can

get it and who can get it farther?

Who can, does this mud stick to the tree?

Does it not stick to this tree?

And so we kind of approach

everything with that.

And that's based in, in our movement

method training and horse boy

training that we did years ago, it,

it really kind of pieced together

things that we were already doing and

experienced and found very important.

And just was that final piece to, to

make it all connect and make sense.

So,

Rupert Isaacson: well you used

the word connect, so Yeah.

I mean, it, it's a

well-known thing within.

Psychology, as you guys both know,

autonomy and connectedness, right?

That's always those, those seem

to be the two fundamental human,

psychological, social needs.

We need enough autonomy that we feel

self-actualized and we need enough

connectedness that we feel supported.

Connected.

And why would that be?

Well, we're herd animals.

At the end of the day.

We're pack animals, we're

middle tier predators.

And our only way of being top predator is

by talking to each other and strategizing.

And the moment one of us ends up two

autonomous, actually out on a limb,

well, that's when the hyenas get you.

But of course not enough autonomy.

Well then there's no innovation.

And it seems that because in a hunting

and gathering society, there are

more opportunities for connectedness

than there are for autonomy.

In, in our evolution, our social

evolution autonomy has been a bit of

a, sort of a luxury, a novel thing.

So we tend to seek it out in the same

way that we seek out sweet foods or

fatty foods, because in the wild, those

are in somewhat short supply and they're

nutrition packed and energy packed.

So we're gonna gravitate towards those.

Now we've, you know, got a society

where that's kind of all that's on

offer and it's killing us, but we're

still, we have a genetic drive for it.

Like we have a genetic drive for autonomy.

But one of the things which

we can often see is that.

Too much autonomy, oddly enough, can also

stand in the way of happiness and success.

And you, you know, the, when the

kids are working out what they

wanna do, how they wanna spend their

time, and making these decisions.

You also, of course, are having

to teach 'em about connectedness.

How do you work with a group?

And specifically how do

you seek out mentorship?

How do you know what you don't know?

And go and find out about

that, you know, as you need it.

Talk to how, how do you, how

do you foster that in kids?

I, I'll go back to you, Catherine,

and then I want to come back to

you as, as well, Nicole, on this.

So the autonomy part?

Yes.

Let's talk about the connectedness part.

Catherine Ward: Well, I think

far autonomy there, you can gain

greater autonomy by the more.

You learn, the more skills

you have then give you more

independence for other things.

And so as the kids come in we of course

train them on the, the routines of what

we have to do for caring for the animals.

So in our outdoor school, it's a five

hour school and the first two to two

and a half hours is spent outside.

When they arrive.

We both, the early childhood, Nicole,

what Nicole's over and the elementary,

they're given, you know, an hour or

so of time to just roam the farm,

go play, connect with their friends.

This is at the start

Rupert Isaacson: of the school day.

Catherine Ward: This is at

the start of the school day.

Right.

The

Rupert Isaacson: sort of

zero hour, if you like.

Catherine Ward: Yeah.

Yeah.

So it's a rival and it's time

for them to transition from

being home to now being here.

Mm-hmm.

And, and they're excited.

I mean, they're social creatures, so of

course they want to see their friends.

And so we allow that.

And I.

We know from experience and from also

our, our, our both of our backgrounds

and our trainings both formally with,

with college and through movement

method and so forth, that kids, kids'

brains just need time to, to adjust.

So we give them that time,

their freedom in the morning,

and then we kind of regroup.

And at the beginning of the school

year, and then as the the months go

on, we're teaching them the skills

of how to care for the animals.

They're given farm jobs.

Each child is given a farm job.

When they reach up to elementary

age, they're put together as teams.

And so now as a team, they

have to do a farm job.

And it might be actually scooping

poop, scooping the horse poop,

putting it in the compost pile.

And then we have another compost

pile where they have to dig it and

fill up manure bags because we sell

manure to the community to make

money back to help pay for the food.

With the, I'll let Nicole speak

about her early childhood kids.

I didn't, I I don't wanna

step on your toes, Nicole.

The, there is a lot of poop talk

because we have so many animals

and there's a lot of poop.

Yeah.

And, and, but with that, they

learn how to observe animals.

Poop lets them know immediately

if an animal is sick.

And, and so then we're able

to tend to the animals.

The the skills of, of how to administer

medications, how to, how to muck stalls,

how to just all the things that go

surrounding taking care of the animals.

But then we also give them

skills on orienteering.

With compasses.

We let 'em we let 'em use tools, we let

them dig holes, we let them be dirty.

And then within our, oh, and we Nature

Journal, we encourage them to do nature

journaling, and then whatever subject

matter we're learning, we try to

encourage them to go find more things out.

Like if we're talking about the

chickens, well then they'll do some

observations with chickens or go

and just hang out in the chicken

pen and have some interactions.

So there's all of that gets connected.

And then as their skills grow,

well then they, they actually

gain more independence.

So by the time we get to later

in the school year, well,

they have more independence to

go do projects on their own.

And Nicole, you'll have to remind me,

there's someone that has said that

I may mess up the quote, but where

you allow children to do dangerous

things carefully, is that it?

Nicole Jones: Danger, allow

children to do dangerous things.

I don't, no.

Catherine Ward: Carefully ca

Nicole Jones: basically, it's,

it's if they're doing it safely.

Yeah.

Like if they're doing it

with enough caution, let them

try, let them take the risk.

Yeah.

Is the.

Catherine Ward: That's one of

the things that, that we got.

I think also as, I think it's Richard

Lu, it's either Richard Lu or Peter Gray.

My personality and Nicole's

personality is very hands off.

We want kids to just

explore and make mistakes.

And what we've tried to do here at

One Acre Farm is within the, the

four walls of the privacy fence that

we've provided a safe environment

that it can be a yes environment,

which is what we learned from you.

We did, you know, I

need to kind of go back.

There was so much that we've learned from

you and with you that, that I'd like to

share with your listeners how we met.

And so my daughter Nicole had

gone into education and and

with into special education and

she wanted to go listen to Dr.

Temple Grandin.

And I said, oh my gosh, I wanna go, I know

of her because of her agricultural stuff.

So we go to this place here in

Houston to go listen to Temple.

And it's much like when you go to a

music concert, you're, you're going

to hear the headlining musician or

the headlining band, but then you have

the little opening act beforehand.

So you were the opening act and you walk

out on the stage and you're, you looked

like you had just walked off the ranch.

You had your jeans.

Rupert Isaacson: I probably

had, yeah, you probably had,

Catherine Ward: yeah,

you've got your long hair.

I mean your, your signature

look that you have.

And I turned, and I, I looked at my

daughter and I kind of rolled my eyes.

Honestly, you hadn't even

opened your mouth yet.

And I rolled my eyes.

I think you were

Rupert Isaacson: the first person

to have had that reflecting to me.

Catherine Ward: And I looked at her,

I said, oh my gosh, we have to listen

to this guy before Temple comes on.

And she's like, it'll be okay, mama.

He probably won't talk that long.

Rupert Isaacson: So, didn't

know me that well yet.

Yeah,

Catherine Ward: yeah.

So, but then your mouth opened, you

started speaking, you started sharing

your story of Rowan, you started sharing.

The things that you did to help him

and how Movement Method and Horse Boy

were all developed and the whole time,

Nicole and I are both elbowing each

other because everything that came

outta your mouth was exactly how we

homeschooled and how they were raised.

And I just kept having, it was almost

like some people when they talk about

going to church and that God is talking

to them, that there's that light shining.

So I did, I felt like, I think

Rupert Isaacson: anyone's made

that comparison to me before,

Catherine Ward: but I did and

I felt like, oh my gosh, this

guy is speaking right to me.

And now I knew that, 'cause I, I

had spent so many years feeling

alone 'cause there was nobody else

around me homeschooling like this.

And, and we were just kind of the

oddballs in the homeschooling community.

So now fast forward, she's an

adult, we're listening to you.

And now I didn't want

you to stop speaking.

I wanted to keep hearing you.

And of course we were very

grateful to, to hear Dr.

Temple also.

But afterwards we made a beeline

to go meet you, buy a book, and

then she and I signed up to come to

training at your place with them.

I think the ranch that summer, it

was like just a couple months later.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

And and it was just so, edifying to now

find that, that what we had been doing

all along had a name or it had, it had

science behind it because you obviously

have done all the science research for it.

So it was a very, it was

a very comfortable place.

It was, it was like, this is the very

next step that our life needs to take.

And at the end of, and I've heard you

do this 'cause I've seen you speak

many times, and when you encourage

people to use their life and what they

have to include people with autism

into their life, you made it very

clear that, that you may think you're

gonna be imparting something to them.

But what in fact actually happens is

that you receive so much more from that

person with autism that they give back to

you and that they are the dream givers.

And, and that's exactly what happened.

So I came back from training and

everything else and we were like, this

is the next step for one acre farm.

So from 1999 to 2016, we had been

doing all these classes and then it

was like, no, this is the next step.

We are going to become inclusive

with all of our activities and we're

gonna start private autism sessions.

And, and we have never looked

back from that decision.

Ever, ever.

So thank you Rupert for that.

Rupert Isaacson: Oh,

it's my great pleasure.

I mean you, where are we

talking about connectivity?

Connection, connectedness I think.

A a lot of us started in this place,

and I'm sure most listeners who

are equine assisted practitioners

started in this place or might still

be in this place of loneliness.

When you tread a bit of a

pioneering path, it's lonely.

And when you are a special needs

parent with a, with a nonverbal kid,

you're, it's lonely because you're,

you're not really talking and the,

there, there's a lot of loneliness.

And so for, for me, I know the

great gift, one of the many great

gifts of doing this work has been

the connectedness of community with

people like you all and like with

the people who are listening to this.

So to realize, oh my gosh, we

actually are all one tribe.

We actually are all one community.

It's just that we're a little bit

spread out geographically from

each other, but we have community.

We're out there and listening to you

between the lines, talking about the,

this sort of zero hour where the kids

come in and get to socialize before move

and socialize and explore together before

they have to sit down and listen to old

boring adult, you know, saying, okay,

now let's look at the DNA of chickens.

Interesting as that is, they are the

fact that they're allowed to have

their time to not just transition

into the school day, but also.

To explore their own

connection and community.

And then you begin to

organize them in teams.

This is actually quite groundbreaking

because you, you know, yes.

You, you hear about

project based education.

It's coming in more and more in

the mainstream, but it's, you know,

we all know that unless you have

a, a, a, a teacher that really

has that personality, it's likely

to be a little bit lip service.

You know, you guys really do it.

Can you, Nicole, talk, talk

to me about co connectedness

and how do you encourage kids?

Because you, you're encouraging to

be independent minded, but you also

need to encourage them to learn

how to seek out information, right?

Who to ask, who to research, how to

just 'cause somebody says something

doesn't mean it's necessarily true.

Dah dah, dah.

You know, how do you approach all that?

Nicole Jones: Well, I think

we have a couple of really

good things working for us.

One being we have the multi age range.

So my class is ages four to seven.

Catherine's class is ages seven to 10.

That comes back being based in the

Montessori practices of having a three

year age range and the importance in that.

And so we already, now we

do have a small class size.

The early childhood class goes up

to about 13 and then elementary

fluctuates anywhere from 13 to 16.

Mm-hmm.

Roundabout per day.

Now that we will have more students than

that during the week, because some come

partial week and some come the full week.

But in a given day it's

13 to 16 kids per class.

So in that 13 kids, we've got a third are

the oldest, or a third are the middle.

And a third are the youngest

typically is how it would go.

So whenever we start a school year,

we're not getting this influx of.

Brand new children.

A, a class of brand new children.

It's 60% of the kids are still

retained from the following

year or from the previous year.

And the new kids coming on

are learning from the kids who

are already having New Year.

Ah, so

Rupert Isaacson: there's

mental, there's age to age.

Yes.

Absolute peer mentorship within the Yeah.

Got it.

Nicole Jones: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: If you're in the

equine assisted field, or if you're

considering a career in the equine

assisted field, you might want to consider

taking one of our three neuroscience

backed equine assisted programs.

Horseboy method, now established

for 20 years, is the original

Equine assisted program specifically

designed for autism, mentored by and

developed in conjunction with Dr.

Temple Grandin and many

other neuroscientists.

We work in the saddle

with younger children.

Helping them create oxytocin in their

bodies and neuroplasticity in the brain.

It works incredibly well.

It's now in about 40 countries.

Check it out.

If you're working without horses,

you might want to look at movement

method, which gets a very, very

similar effect, but can also be

applied in schools, in homes.

If you're working with families, you can

give them really tangible exercises to do

at home that will create neuroplasticity.

when they're not with you.

Finally, we have taquine

equine integration.

If you know anything about our

programs, you know that we need a

really high standard of horsemanship

in order to create the oxytocin

in the body of the person that

we're working with, child or adult.

So, this means we need to train

a horse in collection, but this

also has a really beneficial

effect on the horse's well being.

And it also ends your time conflict,

where you're wondering, oh my gosh, how

am I going to condition my horses and

maintain them and give them what they

need, as well as Serving my clients.

Takine equine integration aimed

at a more adult client base

absolutely gives you this.

Nicole Jones: So, you know.

Five and six year olds are teaching three

and four year olds how to how to observe

body animals operate heavy equipment.

No, I'm kidding.

Yeah.

No, no, not yet.

No, not yet.

You know how to feed the animals?

Well, you can't pull that in the garden.

That's an herb.

We, we don't pull that one,

but you can pull this weed

and go give it to the goats.

So all of those things that.

While us as teachers could interject more,

not, we don't want to, we would have to

be doing that if we didn't have that kind

of peer modeling and mentorship going on.

And it's not only good for the, the

younger kids who get that peer-to-peer

learning, but it's so beneficial.

For the oldest kids in the classroom that

then are building those leadership skills.

And we start to see, especially

that third year and this is true

of Montessori classrooms as well.

We see those kids in that third year start

to really emerge as leaders because, you

know, they've been through learning from

other kids, they've learned from us.

That second year is a lot

more experimental in what they

do and the boundaries they

push and that sort of thing.

And that third year we get like

these really great leaders that know

how everything works on the farm.

They're, they're like the cool kids

because they know where all the cool

spots are and well, I know where to find

this plant and I know where to get this.

And so all these younger kids come

to them and they, and they get to

pass that on to the other kids.

So we all already, with just the multi

ages, get that sense of community

building from kids just asking each other

questions and kids wanting to, to help.

And we do have a very good retention rate.

We don't lose very many students.

Most of them tend to stay with us.

Typically we will where we lose

students the most is that kindergartner,

first grade year, the families that

come to us that they're like, I

just want something for a couple

years before we send them to public.

We do get that and we understand that.

But the majority of our kids tend

to retain and stay with us and, and

then move up to the elementary class.

So we're now in this.

This year was really cool because

this was the first year that we had

kids go all the way through the three

years in the early childhood class

and then graduate up to elementary.

And we've seen this cool change happen

from our pilot year to now where

we've just got these kids that have I

don't wanna say more common sense, but

more farm common sense because they,

they've been with us for these three

years and they know how everything

works and they're, they're able

to go deeper into their questions.

While they may have studied chickens and

horses and pollination and composting in

the early childhood class, well now they

get to dive even deeper in elementary

and go way more into how this all works

at a, at a science based level and not

just, oh, this is, this is a cool lesson.

And so, we already get that

building of community just through

the information sharing and the

way they structure their day.

Our class tends to get really

connected really quickly.

It's, it's a different class in

August at the start of the school

year than it is in December.

Usually around November, December,

we've seen the friendships deepen a lot.

They've.

They ha the kids have learned how

the schedule of the day works, what,

you know, how much freedom they have.

Because a lot of times the, those

new kids that come in, they have

not spent a lot of time outdoors.

Most half of our kids have

never even had pets of any kind.

I mean, not even a fish that, so

a, a big chunk of our kids come

and this is the first time they've

ever been around animals at all.

So we do a lot of working with read,

observing and reading body language

of animals, the sounds they make.

And a lot of the older kids will help

the younger ones learn that as well.

And so anyway, by the time we get

to November, December, our class

has really normalized and, and

we're not having to step in as much.

We are really able to take a step

back a lot and just watch the

children spend their time on the

farm and get into their projects and

observe an anthill for 20 minutes.

Go birdwatching.

I mean, we have birds that build

nests right next to the classroom,

and then we get to hear the

owls in the woods behind us.

So they all go off and do their things

and they play tag and do their games.

But there's also so much immersive nature

involved in it that the children that

are interested in similar things tend

to pair up and, and do things together.

And so the, the friendships

go grow really quick.

And by November, December, we've got a

really, really solid and connected class.

Catherine Ward: To bounce off of

something that she said about some of

the kids that we lose that go to public

school at kindergarten or first grade.

They will come because our school

are we actually go year round.

So we do a regular 10 month from August

to May, but then we have a summer session.

And so those kids have all come

back every summer to do their

two months of summer farm school.

In between one of the, the students

I don't remember if it was our pilot

year or our second year, Nicole, but

we had a, a mom come to us in tears.

So this was during our interview process

of her wanting to enroll her child and

she was crying because her child had

already been kicked out of three other

preschools kicked out of preschool, and I.

And

Rupert Isaacson: for what?

Catherine Ward: For moving,

moving around and not napping, not

sitting down, that sort of thing.

And so being a kid basically.

Yeah.

Being, yeah.

Yeah.

Just being a kid.

And so it didn't, now, while Nicole

and I, we didn't show this to her, but

we're we're shocked at the fact that

a preschool would even kick a kid out.

That was our shock.

Our shock wasn't about,

about the behavior.

And, and so she's like, you're,

so, you're gonna take him?

And we're like, yeah, sure.

You're not afraid.

No, we're not afraid.

No.

And do you know that, that we never,

not once had any problems with him.

He needed that movement

and all of that stuff.

And so I think there are

some kids that can conform.

I don't think they perform at their top

level, but there are also gonna be those

kids that just cannot conform to an

institution, institutionalized classroom.

And and so he then they did send him on to

public school after he finished with us.

And but he comes back every, every

summer and, and, and you don't

Nicole Jones: have to tell him how to

feed the goats and the, he remembers Yeah.

From the year before.

And so it has stuck with him.

So it's, it's been nice to be able

to see those kids come back and see

how, how, how much that this place has

meant to them and how it stuck with

them even three, four years later.

Yep.

So that's a unique thing that I don't

know of any other school that does

that take, because even Montessori

schools won't take kids during the

summer that have been previous students.

So it's kind of a unique

thing we get to experience.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

You guys have gluttons for punishment

'cause you get, you get no holiday no

Catherine Ward: breaks tough.

No.

No.

None.

And I think too for like, say for

that child, 'cause we have other kids

that have gone on to public school.

Actually we had one that went on to public

school and then they took 'em out and

brought them back to farm school because

they were not performing well at all.

And the kid just really wanted

to be back at farm school.

But like with the ones that do, on

the ones that do go on, I think the

amount of time that they've been

given to become independent and

autonomous and the confidence that

they get from learning the skills,

and I think they also learn patience.

They, there are a lot of things that,

that just stroke their, their personality,

that they're, they are, they now

have the skills to conform to those

demands of an institutional classroom.

Rupert Isaacson: What, what's

interesting, what it sounds like

what you're describing is, is emo the

teaching of emotional intelligence.

Catherine Ward: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: And you

know, we all know Yeah.

Academics are one thing.

And we'll get into the academics you, you

deliver and how you deliver them next.

But we, listening to you talk makes

me think of a, a, a, a really a.

Great movement method teacher that we

know in Colorado, Cade, who teaches at

Evans Elementary in Colorado Springs.

And he says that after about is,

and this is very much within the,

you know, the regular system, but of

course he's taking the same approach.

He says that by the time the kids are

about 10 weeks in, their brains have

developed to such a degree through the

movement and the project based thing and

the mutual support that they go from the

standard sort of them and us teacher, you

know, children versus the teacher thing.

'cause that's obviously what they've,

you know, come in with to being able to

go off and learn independently in small

groups in other parts of the school.

And he says, you know, I send out my

little spies, you know, to see what are

they actually doing, you know, and yes,

they are that, it's like he says the,

the, the, the brain development that you

have a different child after 10 weeks,

the, the, the, the, the neuroplasticity

has really kicked in and we, we see

this time and again, but he's not

able to work, you know, as as you are.

Because you know, your campus

is your own and you have the

animals and, and so forth.

Talk to me about.

The academics that you deliver.

So if I was a, if I was a, a parent, say,

well, this all sounds great guys, but you

know, I want my kid to go on and get their

SATs, or if it was in English England, it

would be their GCSEs or whatever, and I

want 'em to get onto college and so on.

Can you really tell me that this

way you're going to deliver the

national curriculum this way?

I imagine that you're gonna say, well,

yeah, sure, but tell me the nuts and

bolts of, of how so, so, Nicole, I,

I'll throw that one to you first.

I'm the skeptical parent.

Well, this all sounds great,

but it sounds also a bit hippie.

Okay.

Hippies actually rule the world, but hey

how can you reassure me that you are going

to equip my child academically in the same

way as if they were in the public school?

Nicole Jones: Yeah.

Well usually when I start out, parents

typically will meet me at a torque.

And so we walk them through the

whole the farm, the classroom, go

over the educational philosophy

and go over the curriculum.

And so at some point in there, I

will throw in, I was homeschooled

right here in this community,

right next door to the farm.

Like, so, and I turned out

to be a normal human being.

Normal human being.

I went to college, I graduated

high school with college credits,

you know, so like, it, it, first

of all, you're talking to somebody

who's proof in the pudding, right?

So Right.

You're the proof of concept.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Right.

Nicole Jones: Exactly.

And so here we are just creating this.

For while, while I did

it at a a family level.

Here we are creating this for a

classroom, small class size level.

And so, starting off with that, when

people find out, oh, you were actually

homeschooled and you went okay, it

eases the conversation a little bit.

But then when, when we walk through

the indoor portion of class because

the kids do spend two and a half

hours outside before we even go

in for any kind of academics.

And then even when we go inside, they're

eating first, washing their hands, getting

some movement out a little bit more before

we even sit into any kind of a lesson.

And so our classroom, the early childhood

classroom is set up as you would

see a typical Montessori classroom.

So we have fine motor work,

practical life, all the things to

help develop the hand for writing.

We've got sensorial work, which

is working with a lot of pieces,

discrimination objects and things

like that, math language and science.

And our science and geography changes

monthly depending on what we're

studying and what the seasons bring us.

So while we advertise, we are

supplemental curriculum to what you're

doing at home, we really do teach

a full curriculum in that two and

a half hours that they're indoors.

And I've had classes as with as many

as 40 kids, and in that two and a half

hours, I get more done with those 13

kids than I ever got done in eight

hours, even in a Montessori setting.

And so, and our parents do get.

A pretty comprehensive progress report

twice a year of things that they're doing.

And so they can look at those things

and match it to, in Texas we have the

teaks, that's the, our Texas educational

code of what they're learning as far

as math and reading and things goes.

But we can teach anything from early

numeracy and learning letter sounds

to, you know, writing sentences and

writing stories to long division.

And so, because we also have the

flexibility to be able to make curriculum

as we need it you know, I've had some

years, I've had a 6-year-old that

was at like a fourth grade reading

level, and so I just made things that

she needed and got and for, you know,

what she was on level for and we're

able to adapt what the kids need.

And so because it's a Montessori classroom

that's already set up for your age range

of about three years of an age range while

it may look like how can you fit three

years of curriculum in here, the materials

that we're using and the curriculum that

we create is so flexible in what we can

do with them, that we can be using this

for, you know, a 4-year-old and then

also be using this for a 7-year-old

in long division and multiplication.

So, it's, it's very, the materials are

very comprehensive in what they're,

we're able to, to offer to them.

So usually once we go through the

curriculum areas and, and that

sort of thing that we don't have

too many skeptics after that.

But, but typically and, and it, you know,

we do have those people where it just

doesn't fit with them and that's fine.

We don't want them to come if, if,

if that's not what they're about.

It's, but typically the people that

seek us out are wanting the small

class size, the movement, the outdoors,

the animals that typically is what,

what the families that come to us.

That's one of the things

that they're wanting.

And the, the families that get the

most out of this are the ones that have

academics lower on their, on their list.

Because as we all know, everything

that they do outdoors as far as the

autonomy, going back to that, that

creates so much executive functioning

skills that, okay, if you've had two

hours outside to be autonomous in what

you wanna do with your day, well then

when you get this big huge math problem,

you now have the executive functioning

skills to go through this math problem

that might take you 20, 30 minutes.

Whereas if I was leading you through

your day and you don't know, I

don't know how to get this math

problem done, I need a teacher to

sit here and tell me step by step.

So we try and it's a lot of educating

parents because a lot of them already

have a feeling of, okay, I, I feel like

this is right, but I don't know why.

Like I, you know, I don't

know how to justify it.

And so once we're able to.

To go through the science of it

and, and show proof of concept.

We really get a lot of people

that just, they take a breath,

okay, this, this is gonna be fine.

And, and then the ones that, that

don't, aren't attracted to those

kinds of things, we, we send 'em off.

We, we don't want, we don't

want them in our program.

Rupert Isaacson: Give,

gimme a concrete example.

Let's say I'm a kid and I, I'm

having trouble with long division.

How would you set up my day?

Like I'm sure you're,

you're strategizing right?

Saying, okay, Rupert's got trouble

with long division, so we're going to

start his day like this, and then we're

gonna look at this thing with animals.

We're gonna look at this thing.

We the horse, we're gonna look

at this thing with the plants.

And then once I am inside and I've gone

through that and now I'm faced with the

long division exercise, how do you present

it to me and how do you help me through?

So can you talk me through

the day from start to finish?

You've got you, you've got your eye on me.

Okay.

Root need to help with the long division.

Off we go.

Yeah.

Nicole Jones: So I wanna make sure if I

know that a kid's been struggling with

something in particular I wanna make

sure that they've gotten the opportunity

to get the movement out in the morning.

We have four different

types of swings on the farm.

So I, you, we try to have, make sure

kids have opportunity for swinging.

I tend to find a lot of the

kids that struggle with.

Reading will tend to be on the swing more.

I don't know if that's a

specific connection, it's just

an observation that I've had.

And so I don't know if it has to do

with those oral skills and things

like that, but I tend to see that.

So we wanna make sure they've

done what they want outside.

They've gotten their movement out.

They've spent lots of

time with the animals.

Usually that will really help if, if

they can go spend more time with the

goats or the chickens or the rabbits.

It tends to calm the, the nervous

system down before we go indoors.

So I want to hopefully see them get

some animal time as well, and not just

the running and, and energetic stuff.

So that tends to help.

And then by the time we go indoors, we

don't structure a kid's day and that okay,

you have to start and we're immediately

gonna do this math problem that you hate.

Once kids in the early childhood

class reach about six years old, they

actually get a work plan for the week.

And so it's, here's your things that

you have to accomplish this week.

You can pick Monday, Tuesday,

Wednesday, Thursday, and you get to

structure your week as you see fit.

Now that doesn't mean that because

you have handwriting and reading this

book with me and long division and

multiplication, that you have to do that

all first we allow for some art time or

something else before we get to that.

So it's more on the teachers to go,

okay, let me observe and, and kind of

help push them and guide them to get

it done when we know it's about time.

But we're still making sure that

they have time for that autonomy

and get those things done.

So when it comes to that long division

problem, maybe they didn't wanna do it on

Monday, maybe it's coming up on Wednesday.

So I know on Wednesday I need to make

sure that around 1130 we're gonna get

started with that long division problem.

We, one of the things that's

unique about Montessori materials,

especially in the math curriculum,

is everything is concrete.

Nothing is done on paper first.

Everything is done with very

physical materials first before

you ever get to anything on paper.

And that's also something we

have to explain is that you're

not to parents, you're not going

to see a lot of work come home.

And while that made to you look like,

oh my gosh, my kid didn't do anything

academic because it didn't come home

on paper, it's because we're using the

physical materials in school and they

might not be at the point where they're

writing it down on paper yet, because

that's a little bit too abstract.

Now, eventually we get to that,

but we're working with place value.

So the unit bead, the 10 bar, the a

hundred square, the thousand cubes.

So they're understanding quantities

and place values before we get to

those really hard problems on paper.

So they start doing addition, subtraction,

multiplication, division with the

quantities before it ever gets onto paper.

So then by the time they're really

familiar with that, well then we

can actually start doing it on.

Paper with the materials, because by

then they're already starting to get it.

And these kids will already start to,

to visualize the math in their head.

And it's when they get about to the

point where they're no longer using

the materials that they're just telling

you, oh, I know the answer is 2,192.

Well then, okay, we're

ready for paper now.

We can, we can get rid

of that and go to paper.

And so a lot of it is the, the

preparatory work for the day, just

making sure they've had their outlet

for sensory and movement needs.

And then they also have autonomy

of when they do those really hard

things that they may not like.

Now it's, it's not that I say, okay, well

you get to do whatever you want this week.

You do have to get these certain things

done because we do need to ensure you

are getting reading done, you are getting

your math done, but there's avenues in

which way you can choose to get that done.

So maybe we're not reading a book,

maybe we're matching parts of a story.

So we, you know, we have a book with

sentences and they have to match pictures

to the correct page or we're matching

pictures towards, so there's different,

different reading aspects we can do.

We've also got where they have

to read an activity and so then

it's like, go jump on a rug.

So then they go jump on a rug.

Okay, go find a cup.

And so then we've got movement

involved in the reading and they're

moving around the classroom,

but they're still doing reading.

So those are the kinds of

things that we kind of.

Add into the class to, to make it work.

I don't know if that answers

Rupert Isaacson: No,

it totally makes sense.

Okay.

And, and I, I think it's really useful to

have this broken down for people because,

you know, you know, and I know we've

gone through this period, this process

of having to learn to become educators.

I did it kicking and screaming.

I didn't want to be,

I just kind of had to.

And then how to break these things

down, as you say, you know, doing

with physical things and then moving

from physical things with moving.

'cause when you move, when you use

physical things, you are still moving.

Right.

And then to the abstract.

And then as you say, making

sure that the, the sensory and

physical needs are met first.

And as you know, with movement method,

we sort of sprinkle the concept

into the movement long before we

ask a kid to tackle an exercise.

If you, if you like, and I, I know with

Montessori it's very similar, you know,

Catherine, when you, when you are now

dealing with the elementary kids and

it's getting a little bit more academic

based again, how, and, and this kid

might well, will, is gonna have to,

at this stage, transition back into

something more mainstream by the time

they hit middle school or high school.

So you, you have that presumably in

your mind, okay, I have to prepare

these kids to be able to thrive.

I.

When they don't have the luxury

of one acre farm what are your

strategies for making sure that

that transition happens at least

academically, relatively seamlessly?

Catherine Ward: I would first say

that most, most of our elementary

kids are obviously because of their

age, they're being homeschooled.

Mm-hmm.

Most of them continue to be homeschooled

even after they're done with

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

After they out.

So you, you are like a

homeschooling backup.

You like.

Yes.

They would consider sending them to

home one acre farm even though it's

a school as part of homeschooling,

even though it is actually Yes.

Sort of isn't really homeschooling,

but Okay, I see what in those parents'

mind, it comes under that banner.

Catherine Ward: Yes.

Well, and, and Nicole said the, the

word earlier that we're supplemental,

so we don't advertise and say

we are a full curriculum school.

Right.

We are supplemental education.

Right.

So, now while the early childhood

that Nicole is over is a

full four day program mm-hmm.

Some kids only go two days.

The elementary is not

offered all four days.

For right now, we've chosen

just two days out of the week.

Mainly because our philosophy of

thinking is that, well, if you're, if

you have a child at home, age seven

to 10, you've chosen to homeschool.

So the bulk of their academics

are gonna be taught at home.

And so we're supplemental.

So they come to us for

two days out of the week.

Now that doesn't mean that

we don't focus on academics.

We certainly do interconnect them, but

we're not providing a full math curriculum

or a full language arts curriculum.

So our, our elementary is

more focused on the sciences.

Of, of all of the

animals, animal husbandry.

But within the studying of those

animals and gardening we, we bring

in reading because they then have

to read books, do book reports.

We bring in geography and history because

we study the migration of animals, whether

it was natural or through explorers.

And, but through that, my main

focus, because they think it's fun

at this point, a book report is not

something they roll their eyes at.

They're excited to write

something about chickens.

And we take it much like Nicole

describes taking things in steps.

We start off teaching

them observation skills.

When they're outside,

we want them to observe.

And then with nature journaling,

what are, what are you observing?

Write that down.

What are some?

And if they're not writers yet, then,

then we'll, we'll write for them as they

dictate what are, what are the adjectives?

What are we, we want them to become more

creative in their writing as they observe.

So then when they come inside

then they can take those skills.

And, and I really try to give them

observation skills of what are they

observing in the books and how to

express yourself in writing, how to

write complete thoughts within sentences.

And.

And so they, they come to that.

So my, while my focus is studying

about the animals, I'm not trying

to get them a vet degree, but it

is a means to an end, I guess.

So we use the animals and their

interest in all of that to

get those other subjects in.

And so hopefully when they're done, if

they leave us at age 10, then they've,

they've got those writing skills and

those research skills and those things

that they need as a foundation to

transition into middle school, whether

it's institutionalized or, or at home.