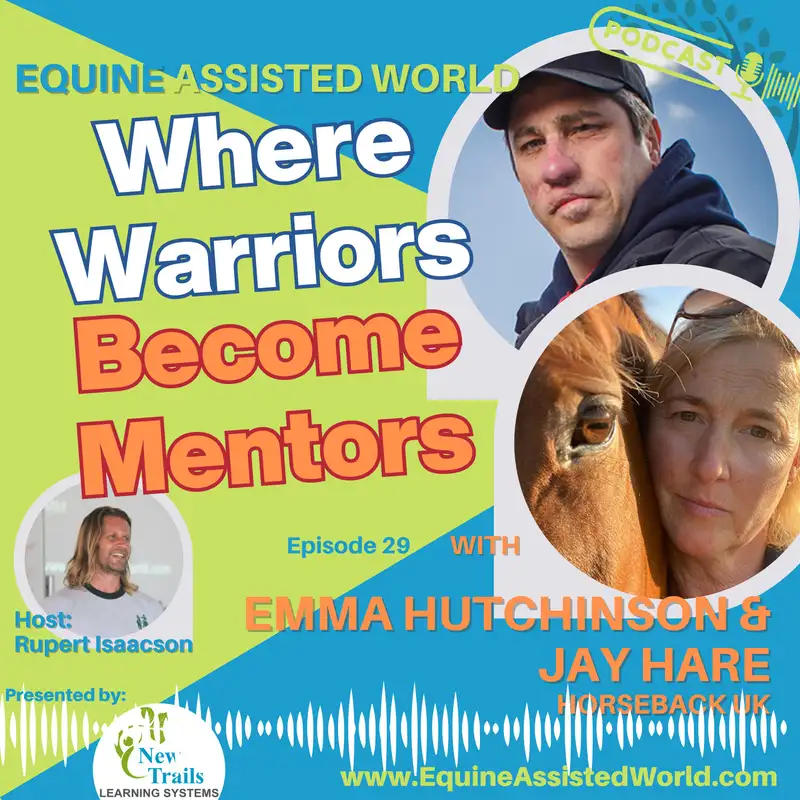

Healing in the Herd – Military Recovery, Youth Empowerment, and Equine Wisdom with HorseBack UK | Ep 29 Equine Assisted World

Rupert Isaacson: Welcome

to Equine Assisted World.

I'm your host, Rupert Isaacson,

New York Times best selling

author of The Horse Boy, The Long

Ride Home, and The Healing Land.

Before I jump in with today's

guest, I just want to say a huge

thank you to you, our audience,

for helping to make this happen.

I have a request.

If you like what we do, please

like, subscribe, tell a friend.

It really helps us get this work done.

As you might know from my

books, I'm an autism dad.

And over the last 20 years,

we've developed several

equine assisted, neuroscience

backed certification programs.

If you'd like to find out more

about them, go to newtrailslearning.

com.

So without further ado,

let's meet today's guest.

Welcome back to Equine Assisted World.

I've got Emma Hutchinson and

Jay Hare from Horseback UK based

up in the wilds of Aberdeen.

They kind of do everything started with

the military, still working with the

military, but then transitioned also

into kids at risk youth all sorts of

programs and populations over the years.

And I would say that in terms of

mentorship for people that are looking,

particularly within the UK to get

involved in the equine assisted field,

horseback UK are really people to look

to because unlike many programs who

target very much one population set

or one type of therapeutic outcome,

horseback UK are unusually eclectic.

And yet they integrate the whole

thing in a really interesting way.

And of course they do this from a

rather wonderful fairytale location up

there in Fairytale Land, which is Aber.

Extremely beautiful.

So, can you guys introduce yourselves?

Tell us a little bit about

who you are and what you do.

Do you wanna kick off Jay?

Jay Hare: My name's Jay Ha.

Jason calls me Jay.

I'm the course director for Horseback uk.

Next month I'll have been at the charity

for 15 years after being seconded here

by the Marine Commandos, back when I went

through my rehabilitation and was healing

after injuries sustained in combat.

Rupert Isaacson: And what do you do now?

You say you are the, you are, you are

directing, but what does that mean?

Jay Hare: So, yeah, it's kind of a pop

title, really is it course director.

But I think what it entails is actually

helping and to design the programs and

the qualifications that we deliver here

as well as in part delivering them and

also working with our mentors so that

we give a good product, a good program,

a good outcome to whether it be our

youngsters, our military, our community

courses, or whoever it might be.

Some just kind of tweaking that constantly

and making sure it's all running well.

Like any good business, charity

organization, it should look

like a swan skimming across

the top of that lock or lake.

But underneath there's always legs

kicking, so we're making sure that each

one's working the way it should be.

Cool.

All right, Emma, tell us about you.

Emma Hutchison: So I'm Emma Hut.

The charity.

Charity.

So I I run the equine side of it, but

I also do the strategic and the, the

sort of the fundraising and the, the

desk is just piled high with paperwork,

with all sorts of stuff that you have

to have done to, to run a charity.

But fundamentally, as I say, my

passion has always been the horses.

And I am still fascinated.

We just started running the,

the programs again this year.

We have a couple of months where

we kind of try to get on top of

all the paperwork and everything.

And the last few weeks we've

gone back to running the courses.

The horses have had a few months off,

and they just amazed me about how it took

them a couple of days to get back into

it, but how they just slot back into it.

They know their jobs and they're just

funny old things that, you know, some

of them, like some people and some of

them don't like other people, and they

know what they want and they know how

to do their jobs, and it's just, just

me that they're, they're just amazing.

Rupert Isaacson: All right.

So Jay I want to start with you.

I remember when I was visiting you guys

and we were doing various exercises

together in the arena, it took me a while

to realize that you had a prosthetic

leg, you were moving on it so naturally.

So, athletically.

And then at a certain point

I say, oh, hold on a second.

He's, he's on a prosthetic leg in a sand

arena, kind of jumping over poles and.

Blocks and things.

Emma Hutchison: Is that

when he took it off?

Rupert Isaacson: I think

he did take it off that.

So no, I think he took it off so he

could beat me over the head with it.

But the injuries that you sustained

you, you were a marine commando.

Tell us about the, your life prior to

that, your life during the process of

being injured, if you like, your recovery.

How did horses come into this?

Why and why did it make you feel

that you wanted to do this as a

calling, as a, as a vocation really.

Jay Hare: So yeah.

Okay.

Very quickly, I suppose.

I was born in, born in Greece.

We came over to Wales and

I was brought up there.

I spent a lot of time in North

Wales and there has always been a

horsemanship connection in my family.

Normally with my grandfathers.

So I agree with some people.

They say sometimes it

can skip a generation.

So maybe it hit me.

I had an interest, whether I was

trying to, you know, pat one in a

field or something, or, or asking

can I ride one, can I ride one?

So I did at an early age, go for very

basic riding lessons and going on to, you

know, trek centers and things like that.

And then I forgot about it, completely

went to college, studied engineering.

Always wanted to join the

senior service, the Royal Navy.

And one day I went to a careers

fair and met this six foot four

big bloke with a Green Beret.

And I said, who are you guys?

And I said, well, we're part of the

Royal Navy, but with a, with the

elite soldiers of the Royal Navy,

with the Royal Marines commandos.

So I dug a little further, you

know, asked some questions and I

thought, yeah, that's, that's me.

I'm out playing rugby.

I'm getting dragged

down by the gamekeeper.

I'm probably in a bit too much

trouble at that early tentative age.

And I thought, yeah, as soon as

I finish and I'm, I'm gonna go

off and join the Royal Marines.

And I did, at 19 years of age, I joined

at the 11th of September, 2000, passed

out an original, there's a high attrition

rate in what's called the highest and

hardest basically basic infant in the.

So about 40 of us started 11 of

us, seven to 11 of us trying to

remember the numbers passed out.

Original.

That's without injury, that's without

being back to or sent back at class.

And I headed up to Scotland to

four five Commander conducting

some, you know, guard duties.

And basically went back from

guard, gee, one evening to see

planes flying into buildings.

I said to the guys in the room, I

said, what, what film we watching?

They said, no, Jay, this

happening real time.

This is a terrorist attack.

And from there, that changed the

whole landscape of, of combat for us.

We were the original troops asked

to go out to head into the hills.

That's our specialization in

four, five Commander to go into

the mountains and arctic regions.

So we requested and off we headed.

Subsequently I did three tours.

I was injured twice.

Once by a suicide bomber

on my second tour.

And I got fit, healed, recovered,

led a team again on my third tour,

and unfortunately stepped on an

improvised explosive device that

blew my last leg off below knee.

So it was an amputee in the armed

forces that's called a scratch.

'Cause it's not through

knee or above knee.

So that's maybe why I can maneuver

a little better than the average

person's, you know, higher amputation.

I lost digits to my right,

lost right arm, right leg.

But I.

Onto the radio to call some things in.

And I, I lost my facial identity.

My face was blown off and a degloved.

So over the next few years, that was

the 5th of November of all dates to

play around with fireworks and bombs.

It had absolute to be the 5th of November.

It took me about six years to

get my you know, the surgery.

I had about 11, at least 11 surgeries

to rebuild my face from using bits

of my forehead, rib cartilage from

my ears and all sorts of stuff.

So, yeah that took some time.

And in that time I needed

something to occupy myself.

I was a young guy, you know,

you're 27, 28 years of age, you've

got a family, young family, but

you've still got that adrenaline.

You've still got those ghosts

from being on previous tours and

you're worried about your future.

But mostly you're trying to sort your

head out whilst you're trying to sort

your body out and necess, you can't

necessarily do that at the same time.

So there is a time for each of those.

I found out about Horseback uk.

I found there was a, a former Royal

Marines officer and his wife, who was

a police officer working with horses

up in the Highlands of Scotland.

They approached the commando

unit and said, well, maybe the

guys wanna try some horsemanship.

At end of the, the horses got

four legs and I've got one.

I thought, well, that, that makes sense.

There's a bit of, you know, mobility

with dignity and it's Western, so

it's that kind of iconic cowboy

imagery that it conjures up.

And I thought, yeah, let's

go, let's go take a look.

And as soon as I got here,

it was under my skin.

I loved being around the horses.

I loved especially riding the

horses, but I found that there

was more of a relationship working

with the horses on the ground, that

they were kind of flight animals.

They wanted to run away

very much like I did.

I needed to find my herd,

horses needed to be in a herd.

So eventually I came back

to mine and that's me.

Yeah.

15 years now.

So I've never left.

They can't get rid of me.

Rupert Isaacson: It, well, one of

the things which I was really struck

by when I was up with you all was

it really did feel like a family.

And obviously, you know,

Emma, it is a family.

I mean, it's you, your husband,

your daughters are involved.

They're great horse women as well.

So like anything that's led from a

family from the inside this sort of

brings a lot of love and functionality

and multi role, you know, cross

fertilization into the thing, but.

Sometimes things that are very family

run like that, it can feel that

one's a little bit on the outside,

you know, from that core group.

And it was very, very noticeable.

I think Jay, from what

you're saying now, yeah.

It makes a lot of sense that there's

this, it was, it was like sort of yeah.

Clan headquarters and you're sort of

part of the clan and part of the family.

And I, I could see how your horses

as well responded in this way.

That the whole, the, the, the,

the horse herd and the human herd

were unusually well integrated.

And I was thinking, you know, why

is this, is this partly because

they're not less like a riding

school where they all go off, you

know, back to their suburban lives.

Oh, this is sort of up in Scotland.

Everyone's living there, sort of to some

degree in this slightly wilder place.

Is it, is it that, is it,

you know, whatever it is,

there's a special magic here.

So Jay, talk to us about this

healing process of trying to find

your identity to lose your face.

That's huge.

And I think that's something which

very, we, we can try to imagine

it, but we can't imagine it.

Talk to us about that process of

that loss of identity and how that's

informed the work that you do.

Jay Hare: So the, yeah.

There.

So you, you kind of,

you're a marine commando.

One minute.

You think you're the steely eye dealer

of death that, you know, heads out and

does the nitty gritty stuff that used to

seeing war films and reading comic books.

You look like your father.

You think yourself rather

handsome in your uniform.

And the next thing you have

gotta stick on those a false eye.

And you can't quite smile

properly because you know the

scarring and things like that.

You don't wanna look at yourself in the

mirror 'cause it reminds you every day.

You kind of look into your partner

and your wife and stuff and going,

oh my God, this is not the person

that you walk down the aisle with.

You are walking down the street and you're

worried that your nose is gonna fall off

at any moment, different times of year.

I was born in Greece, so I can really

easily, so I'd have to change from

my winter nose to my summer nose,

and then from my summer nose to

my winter nose, you had to super

glue it on when it was hot weather.

I used to make a joke that I'd go for

lunch with some pals and you know, if I

sneezed my eye would go into your salad.

My nose would go into your pint.

My leg had fall off.

So the lad and the lads nicknamed me Mr.

Potato at one point, which so

with that, you know, working with

horses, they don't judge you.

They judge how you are

with them in that moment.

They don't care about looks, they

don't care about degrees, they

don't care about the car that you

drove up in, on the motorbike.

You just hopped off, whatever it might be.

They want to be with you in the moment.

And that gave me that time to, to assess

what I was gonna do and think about my

own behaviors and who I was becoming and

who I wanted to become and who I had been.

So yeah, it could be a little bit

forward, a little bit ambitious,

a little bit strong, a little bit

too full on that doesn't work with

the horse, but I can't be passive.

I can't let them walk all over me

because then they'll try and take charge.

So again, it's trying to find that

balance and that for me is what I found.

Yeah.

Riding, looking like a cowboy, heading

out to the states and all the stuff that

I did after all spec, archery, fantastic.

But it was actually finding

out who I was and where I kind

of fit in into this third.

And I.

That fascinated me.

So the more I read, the more books I

looked at, and Emma was constantly feeding

me, read this, read that Jo, same word.

Have you seen this YouTube documentary?

Have you seen this?

Have you seen that?

And I started to think, yeah, there is.

I believe in what Winston Church said.

There is something about the outside

of a horse that's good, the inside

of a man or a woman, obviously.

But you know, Winston Churchill, right

or wrong or whatever politics, I felt of

him as a very strong leader, a powerful

man that suffered with the black dog.

When that darkness comes, when you

suffer some of the kind of traumas

that have been through your life

and you try and comprehend what's

happening, working with a horse enabled

me to do that and not clock watch.

It wasn't being with a counselor that

say, right, you've got an hour with us

off you go, tell me how you're feeling.

Can you watch a war film?

Can you listen to music,

watch your love life?

Like, no, I don't.

I wasn't interested

in

Jay Hare: that, any of that.

I just wanted to work with

the horse on the ground and

find out what made them tick.

How you could train with them, how

you could communicate with them.

And people used to say, you know,

do you go and see a a, do you go and

see a, a therapist or a counselor?

And I said, yeah, I do.

And I'll tell you how meant to pay them.

And they, oh, it

thousands.

And that me started that, that

beautiful journey, that on

which is helping.

Rupert Isaacson: When you are, when you're

dealing with that loss of identity it's

obviously gonna give you a lot of empathy.

And I presume that a lot of the people

that come to you as clients must

be wrestling with similar dilemmas.

Are you working with populations that have

also been physically maimed in that way?

And then also when you're dealing with

say, youth at risk youth or troubled

youth who are going through identity

crises in a different way, but of

course have not yet seen the face of

suffering in the way that you have.

How do you walk that line between

thinking, you know, you, you don't

know what suffering is, you don't

know what loss of identity is?

I do.

And also, yeah, but at the same time,

everyone experiences it in their way and

just because they haven't experienced it

in the way that you have, which is so raw

and so extreme, doesn't mean of course,

that the way in which they're experiencing

is not driving them towards maybe

some negative outcomes in their life.

Talk to me about how you walk

that dance and with helping others

there, because what you've gone

through, you, you, you, you could.

Be forgiven for almost going down a bit

of a bitter path and saying, well, you

guys, no one can understand, you know,

the extent of what I've gone through.

And, and you'd be absolutely right.

People couldn't, and at the same time,

you can use this as an empathetic tool.

Talk to me about that and talk to me about

how the horses have helped you to make

it a tool rather than a, a hindrance.

Jay Hare: I think working with our

military veterans, if we go into those

first and I'll talk about the youngsters,

is it's a lot easier for me because if

I wear shorts or you take a look at me,

you sort of go, right, he's either been

in a bad accident and then you find out

it's military and you go, oh, right.

That must been time and service.

So it's like, okay, that's fine.

Yeah.

We get it.

Right.

There's a respect that comes with it.

Respect that comes to that,

because you can see Yeah.

This guy as a battle, et cetera.

Yes.

I totally empathize with guys

and girls that don't have the

scars because they're internal.

Mm-hmm.

So as much as you have to deal with

your physical trauma, along comes the

mental trauma to try and adjust to life.

Try not to be bitter.

The outward looking,

I the.

Think is such thing as can't,

don't tell me I can't jump over

those horse hurdles with you.

I will do it.

I might have to take a break, take

leg off, readjust to run back again,

but I'm still gonna do it with you.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Jay Hare: That's maybe the way

I was brought up with a military

kind of family and grounding.

Definitely for the training I received,

but also the way I like to lead my life.

I like to remind our military community

of who they are through the horses

because they're resilient creatures.

They don't

Jay Hare: sit and feel

sorry for themselves.

And then with the youngsters is,

is adding those layers and saying,

yeah, this might have happened to me.

I'll tell you why.

It's okay to ask a question

point and gossip in the corner.

If you wanna know, I will be open and

honest with you as I possibly can.

Don't ask me about the question of how

many times I've I pulled the trigger

and how many, all that sort of stuff.

Those are questions you don't ask a

serviceman, but if you wanna know what

pain I went through, how I dealt with it,

what I felt about myself, I'll explain

it because we can talk about this.

I hope it never happens to you

in your life, but life is life.

So things might have happened to

you in the past, the way you've been

brought up, the way you've been.

Let's try and build more layers to

that onion to build a little bit of

arm, a little bit of strength to you,

some inner strength whilst keeping

that empathy and being able to still

love life and love other people.

And through the horses you can

do that with the youngster.

They can start to show empathy towards

another creature, another being.

Then you are winning and that assists

the school and that assists the

counselors and that assists their growth.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah, I should imagine

too that because you do carry the scars

of battle, it is got to help people who

are much younger than that looking out at

their lives with some perspective to say,

okay, wow, I see that this can happen.

Okay, this has happened to

this guy and yet he seems he's

here in a position to help me.

This must give quite a gift, I

would think, to some of those

kids who are already facing a

certain amount of hopelessness.

Even if it's only perceived

hopelessness to them, it feels real.

Do they ever say that to you?

Do they say Yeah.

You know, being with you, looking at

you sit hearing about your experiences?

This puts my world into perspective.

What sort of feedback do you get?

Jay Hare: I start off with, with

getting a lot more girls through

than we do boys at the moment, but

it's always, I've got this problem.

I've been pigeonholed with this,

but they wouldn't say that.

So they'll say things like, I've

got a adhd, medicated, and I'm told

I'm useless and I can't do anything

and I'll never become anything.

And I go, really?

You've got a super power.

You have got this ability to think

a hundred miles an hour of a hundred

different problems and solutions and

come up with them whilst people are still

just getting out the seats to put the

jacket on and go deal with one of them.

Now we can sit here all day and talk

about the issues and the problems,

or we can go and find that light

bulb moment for you because I've got

a DHD, so is this team member, so

that team member, in fact they've

got a bit of this and a bit of that.

So let's go and be those adventures.

Let's go and find what it is

that really makes us tick.

And we can do that through the, through

working with the horses on the ground and

then up to the level of where they'll be

able to sit on them, if that's depending

on the course and what we're doing.

Does my experiences make a difference?

Yeah, possibly because it's visual.

Mm-hmm.

Jay Hare: It's that ability to say

to a youngster, yeah, this happens,

but it, it doesn't define you.

It can just make you stronger.

And I.

Probably isn't, might be

midweek, it might be into the

second phase of the second week.

It might be into the 12th of development

program takes go, you know what

I've wanted ask you this question.

Or it could be 3, 4, 5 years later,

whether had this where I youngster, he

served coffee at all places, take up range

with my, and this tall came up to me.

He wasn't tall when I first him, he of

the group and he said said, how you doing?

See you?

And it was on the tip of my tongue.

I was yeah, I knew I'd worked with him.

I remembered which group, but

I couldn't remember his name.

And I was, yeah mate, I'm doing well.

I'm doing well.

Whatcha up to, oh well I'm working here.

And he got called away after

dropping off the coffees and

you know,

Jay Hare: cakes and stuff.

And I went back and I

said, Liam, how you doing?

Good to see you.

How you doing buddy?

And he says, I'm doing well.

I've got this job.

I've got another job and I'm

working jobs at the weekend.

I'm gonna study psychology in Edinburgh,

but I'm gonna take a year out and I'm

gonna go and travel around South America.

I went, oh my goodness.

You were what was described to me as

a youngster who was disengaged from.

I was called something, it was a lot rude.

When I was in school, I was

called, but I shook it down.

I gave a, I said, I'm so proud of you.

Absolutely brilliant.

That's, that's, that's a success story.

That's amazing.

And he said, I want to study psychology.

'cause I wanna be able

to help people like uj.

I'm not a psychologist,

I'm not a counselor.

I'm just someone trying to do

something good and have found horses

is the great way of doing that.

But I inspired a youngster to go

into that world and yeah, I'll

tell you what, I'll be honest.

Yeah.

Someone peeling onions there

and it got a bit as I left.

And I,

and I hear a lot of success stories.

You're not gonna hit on point every time.

Some you just can't help.

And some go along a different track.

They take a different route.

But when I hear stories like that,

I know I'm doing something right.

I know that we are doing something

right and I know that horses are

working because it just gives people

that ability to think outside the box.

When you're doing equine

assisted services,

Rupert Isaacson: when you say to

them let's go on an adventure.

Talk us through what some of

those adventures look like.

And you also said that some of the work

can be mounted, which I love because as

you know, with Horse Boy Method, we do a

lot of mounted work, but within the equine

assisted world, it's often not mounted.

So I'm intrigued by that.

Talk us through what these

adventures might be and what

Yeah, just talk us through it.

Jay Hare: So some of the basic ones are

actually being out in the fresh air.

Realizing your outdoors, looking at

nature, starting to look at the world

around you and being aware of it, being

able to touch it, feel it, get amongst it.

Be within it alongside the horse.

And noticing subtle little things like

behaviors, like, eye contact, that

pressure that can come from eye contact.

That that ability to

communicate without speaking.

You know, how do we do that?

How do we pick up on the

energy of each other?

I had a we're running

a course at the moment.

As a young girl, she gets

quite angry about things that

she gets confused with stuff.

And today I said to her, look, I

can feel the anger coming off you.

I can feel your frustration.

What's going on?

And she told me, and I said, do you feel

that with a horse when you get frustrated

because a horse can pick that up from you?

I didn't realize I gave that off.

And I said to some people,

you do, you give that off.

It's not forging her arms and sulking.

It's just this energy you give

off and the horse pick up on that.

So that starts with that kind of a little

adventure, but talking about ourselves,

which, which one of the horses are we,

Ann is really good at pairing you up with.

Personality to, I don't

know, what would you call it?

Your ality?

Mm.

It needs to be opposite

or are they the same?

Sometimes they can be

opposite in their characters.

And on the spectrum of, of who they are.

But then also we've seen horses that

just join with someone who's maybe

on the autistic spectrum and it,

the horse just goes to them and all

of a sudden they're partnered up.

And we've seen that twice this week

of horses we didn't think would wanna

work anywhere near some of these kids.

And they were like, no, we love them.

This is who we want.

We love them.

So that's an adventure.

Yes.

They can take them out with the horses.

We can go and do bushcraft.

We can ride out, we can

do camp outs and things.

Just something, it's almost like you

said to us, Rupert, that you follow

the kid and go with them and take the

horse because that's the kind of conduit

that's the bridge a lot of times.

So we have lesson plans, we have

learning outcomes, objectives,

qualifications, all that sort of stuff.

But sometimes, and we've had it this week

and we had it today, do you know what

change to what we were gonna do Today

is gonna happen tomorrow or it's gonna

happen Friday today we are doing this.

We're changing it.

We tell them, we explain that to them, you

see a sigh of relief and they go, yeah,

that's exactly what we wanna do today.

Again, you're picking up on that energy

from the youngster and you're picking

up that energy from the horse and

you're mixing it together and going,

right, let's get the best outcome.

So whatever adventure it

is, use your imagination.

Go out there, have fun,

try different things.

And that's exactly the conversation

we had when you came up to visitors

and I went, yeah, I get this guy.

I totally understand it.

That's the way I'm,

Rupert Isaacson: you know, when people

think of Bitcoin assisted world, I

think they often think about people

working in arenas in a very, kind

of fairly controlled sort of a way.

You're out there, you've also,

you've got a lovely indoor arena.

You've got lovely round pen and outside

arenas too, but you also have the forest

and the open hill and you know, not

every, not every equine assisted place

of course, has that kind of access.

But there are some I've seen

that do that don't quite use it.

And I'm always like, oh man.

But that's kind of where the magic is.

It's, it's out there in nature.

You, you mentioned going out and

even camping out with horses.

Paint a picture for us

about how that can look.

What, how, how might you organize that?

What kind of people might you take on

that and, and how might that play out?

Jay Hare: So we've changed

various different programs and.

We have one that is a personal

development three phase program.

So each phase being a week

long, it's residential.

And that culminates in a final exercise

where we take the horses out into,

you know, the Highlands of Scotland.

We used to ride them out

and then we camp out.

We had the horses out.

Depending on the time of year, you

can have problems with kind of,

you know,

You know,

Jay Hare: Mid high and,

and all sorts of stuff.

So we've gotta be careful with that.

Or we can bring the horses back in Yeah.

From that and leave our

guys out on the ground.

So now I think looking at the kind

of wellbeing courses that we're doing

is actually walking out to get the

horse, spending time out in the field

looking at herd behavior, which talk

to you about, she takes that part.

Yeah.

And understanding who we are, where

we sit in the herd, what type of horse

do we, what type of personality have

we got at all times being outdoors.

And the more outdoors

we can be, the better.

So sometimes it might be as simple

as just standing outside and just,

you know, doing some breath work,

maybe alongside the horses, trying

to mirror the horses, inhale and

exhale with ourselves, trying to work

out our heartbeat the same as them.

Those are the kind of.

Out a little bit more on other

programs, we can make them more complex.

And we, as I say, we are lucky here.

We we're in the Highlands of Scotland.

We suffer some heavy winters.

We're just coming out kind of one now.

I'd say that was too heavy.

But the springs here, we're

starting to get that energy.

The horses are getting lively again.

Yes.

Let's, let's start having

some adventures again.

What that looks like depends on the group,

Rupert Isaacson: right?

You mentioned Bush bushcraft.

Of course.

That's dear to my heart.

You know, having lived with hunters and

gatherers, and I, I know very much the

healing power of touching, sleeping,

being, working with nature in that

intimate way that our DNA wants, because

that's who we are, we're organisms.

Again, this isn't something that's

often integrated into equine assisted

stuff, so I'm intrigued about talk,

talk to me about the bushcraft that

you do and, and some of the changes

that you see with people with that.

Jay Hare: The bushcraft is,

again, getting us outdoors.

It's something that we brought

into the course you know, many,

many moons ago, various experts,

professionals coming into help with,

with training and things like that.

It, it keeps you, if you,

if you've got a deficit.

For instance, it is a fantastic way of

doing so many different lessons and moving

around in that, that classroom because

it is a classroom and if it's underneath

an old drops parachute with a fire going

and you dunno, you're talking about

how to build shelters or you're talking

about plan N in your survival situation.

Or if you're simply ma making string

the bows and arrows out of nettles to

you know, different forms of making

a fight, you can switch and you can

pick up on the energy of that group.

Go, okay, we're losing a bit here,

let's put that to the side and

let's move on to something else.

Or maybe that particular group

is into that particular lesson.

Okay, I can take the group and I can split

the group and mix it up a little bit.

So there's so many dynamics to do

in bushcraft, but it's, it's earthy,

it's salty, it's getting your

hands dirty, it's being in nature.

It's noticing things.

It's learning things.

It's not a classroom environment yet.

It's the best classroom to be in.

Rupert Isaacson: What, what

sort of changes have you seen?

Everyone's got, you know, their stories.

What stories spring to mind

for you of transformations

you've seen using bushcraft?

Jay Hare: I think kind

of attention to detail.

When they start to notice things

and they start to learn a little

bit how they then, how they then

become the teacher to the others.

And that is fascinating because, you

know, they're learning when they're

starting to teach what they've

learned to other people, right.

Which ingrained in that, in that

that kind of psyche with them.

So, yeah.

I, I love it when a teacher or

staff member comes up and they've

been trying for ages to talk about

biology and photosynthesis and, you

know, whatever it might be, how a

tree grows and things and how roots

work and how fungi works, et cetera.

And the biology teacher comes up

that they've not maybe jelled with

and they've had a bit of abrasion,

they've rubbed up against each other.

All of a sudden the youngsters sitting

there going, and this is how this works.

This is how that is.

And this is called a so and

so, and this is a tree and

this oak tree and this is this.

And the teacher's just kind of, okay,

that's amazing because few weeks

ago I was trying to get this to you.

Now I've got somewhere to go.

Now I can pass on that little bit of

knowledge because we've got a commonality,

we've got an interest together.

And that has repaired so many

relationships with working with

these schools and organizations.

I think that's, that's just golden.

That's ace.

Rupert Isaacson: Brilliant.

I mean, it's, it's, I know this

is what you do every day, but it's

cutting edge work and it's so much

more rich and layered than simply

going into an arena with a horse.

Not that that's not a wonderful

thing to do, but you guys take it to

a level that I am unused to seeing.

And it's, it's, it's extremely impressive.

Jay.

Alright, I want to ask Emma

some questions now, Emma.

How, why did you start this

whole thing in the first place?

Like, you must be mad.

Why, why would you, why, why would

anybody start an equine thing, let

alone in Northern Scotland where the

weather is brutal and, sorry mate.

Are you alright, ed?

Yeah.

So Jay has to leave right now, listeners,

so if you've got any other questions for

him, just email us and we'll we'll pass

them on and we'll get answers from you.

Jay, thank you so much.

It was an honor.

All right.

Cheers, ma'am.

Okay,

Emma Hutchison: so the

whole thing started.

We moved to the property that

we're at now 16 years ago.

And the idea was, is that we would be

here and we were going to breed port

horses and we were gonna take people out

in Western to the beautiful side hills.

And that was the idea.

And then we'd been here for, so.

And moved here in the November, in

the December we had some friends come

around and quite a few of them had

come back from Afghanistan at the time,

and they were, they were not in a good

place either physically or mentally.

And we sat around a big bonfire.

And then during the days, we, at the time

we had I had a horse, jock had a horse,

and the, the girls had a couple of ponies.

And these guys, we just

interacted with the horses.

We were just outside and one of the

guys said, this is what we need to do.

This is how guys need to decompress

after they've been to war.

This has been a real kind of breath

of fresh air for me, and this is

what I, fresh, I absolutely needed.

So that was really the start of it.

And of course we thought, you know,

I'm quite enthusiastic about things,

stocks extremely enthusiastic about

most things, and we just said, right,

well, we're gonna do something.

And it was 2008 it was the height of

Afghanistan and it was when we were, we

were all watching the news and seeing

the coffins come back and it, you know,

it was, it was a pretty horrific time.

So Jock approached four five Commando,

which is in our growth, just over the

hill, about an hour and a half away, and

went to the CO there and said, look, you

know, we've got this property, we've got

some horses, we've got a bit of a rundown.

The who have been injured.

The co sent their injured troop.

So there was a

Rupert Isaacson: co being

commanding officer for those

who are not British, right?

Yeah.

Or,

Emma Hutchison: Sent their injured

troop, which was called Harden Troop.

And there must have been probably

about 20 guys came up for the day

of, which Jay was one of them.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Emma Hutchison: And these guys

all had, they were all young.

They all had life-changing injuries.

So you're talking, so Jay had

one leg, we had a triple amputee.

We had, you know, an 18-year-old.

It, it was, it was life-changing

for us to see it, to actually

to to be there and hands-on with

these guys and hear the stories.

It was we both felt that

we had to do something.

We didn't know what it was that we

wanted to do or what we could do.

But we, we knew that we

wanted to do something.

So we are in Aberdeenship.

We have Aberdeen City about 30 miles away.

Obviously Aberdeen is the

oil place of the, the uk.

And so we went and approached some

of the oil companies and said,

look, you know, would you like

to be involved in this project?

And they, of course, they

said, well, what project?

You don't have a project.

So, we had to then go through the

process of saying, well, what is it?

And it just evolved from that really.

And as I say, then Jay came

up with several of the other

guys and it has just evolved.

And we got more horses and we got more

people, and then more people got involved.

And once you get onto that rollercoaster,

there was no getting off really.

And the, the, I mean, my

children at the time were three,

five and seven or something.

So they were involved

right from the start.

We had no facilities outside.

So the kitchen was our kitchen.

The toilet was our toilet.

The fridge was our fridge.

The, the kids' lunch and dinner

frequently went missing because it

was eaten by the course attendees.

And so it was, it was quite challenging

to start with, but we eventually

managed to get some traction.

Some people heard about

what we were doing.

The British military at the time crawled

all over us because we were looking

after their injured, still serving guys.

So we had to every risk

assessment, everything was just,

you know, how are you doing this?

How are you looking after them?

You better make sure that you

are not damaging them further.

And there had been some incidents

in other places where people had

been on horses and fallen off

and, you know, been more damaged.

So, yeah, everything was.

Massively sort of overkill to, to make

sure that we protected these guys.

And so we were one of the only

places where serving guys, serving

injured guys were being sent

Rupert Isaacson: forward.

Well, that, that was gonna be my question

when you said that Jay and the others who

came up, you know, had these life-changing

injuries, and I assumed clearly wrongly

that when you had injuries like that,

you would be automatically discharged.

Yet you said they were still serving.

So what capacities were they serving in

and was the idea that they would then stay

in the military or transition out of it?

What, talk us through, because

I'm, I'm not familiar with that.

With that sort of infrastructure at

all, I, I, I've worked, we work with

a lot of veterans, obviously, in our

organization, but by the time we meet

them, they're veterans or we meet

with people who are still serving,

like we work with the German army

but they're not necessarily injured.

And so they're sort of

in between deployments.

So that seems to me a really

interesting gray area.

If someone has a life-changing

industry in injury, but is still

serving, how, how does that look?

Where, where would you guys fit

in with that, with your service?

If you're in the equine assisted

field, or if you're considering

a career in the equine assisted

field, you might want to consider

taking one of our three neuroscience

backed equine assisted programs.

Horseboy method, now established

for 20 years, is the original

Equine assisted program specifically

designed for autism, mentored by and

developed in conjunction with Dr.

Temple Grandin and many

other neuroscientists.

We work in the saddle

with younger children.

Helping them create oxytocin in their

bodies and neuroplasticity in the brain.

It works incredibly well.

It's now in about 40 countries.

Check it out.

If you're working without horses,

you might want to look at movement

method, which gets a very, very

similar effect, but can also be

applied in schools, in homes.

If you're working with families, you can

give them really tangible exercises to do

at home that will create neuroplasticity.

when they're not with you.

Finally, we have taquine

equine integration.

If you know anything about our

programs, you know that we need a

really high standard of horsemanship

in order to create the oxytocin

in the body of the person that

we're working with, child or adult.

So, this means we need to train

a horse in collection, but this

also has a really beneficial

effect on the horse's well being.

And it also ends your time conflict,

where you're wondering, oh my gosh, how

am I going to condition my horses and

maintain them and give them what they

need, as well as Serving my clients.

Takine equine integration aimed

at a more adult client base

absolutely gives you this.

Emma Hutchison: So, at the time, so again.

These guys, it was unknown.

Nobody really knew what was happening.

All they knew that they were sending

more guys out and more guys were coming

back with these horrific injuries.

So at the time, Jay was told,

don't worry, we'll look after you.

You'll always have a job.

Don't worry about it.

Because of course they didn't

wanna pile any further stress.

They've all had these, they

all, a lot of these guys thought

they were Korea military guys.

They were going to be in the

military for their career.

And suddenly this career

has been cut short.

They didn't know what,

what they were gonna do.

How are they going to finance their,

their families and all this sort of stuff.

So, the, the military said, don't worry.

We will, we will keep you in.

The reality of that was two or

two or three leaders down the

line, that's not gonna happen.

So they were told, well, you,

you do have to transition out.

There were various sort of funds

available, transition funds to help

guys, but ultimately the ones that who

were, were no longer physically able to

do their job, had to leave the military.

So it was a big change because

I say I, I think a lot of these

guys were left very angry.

It wasn't a decision that they had made.

They didn't want to leave the military.

And they were forced to.

And as it stands now, we still

work with serving military guys.

And they have there are kind of recovery

offices within regimens and stuff.

So if somebody is either has a.

Or more often now is, is suffering

from sort of mental health issues.

Then they have recovery officers

within their, those departments

and they will work with them.

And those recovery officers are

quite good now at looking out with

and pointing serving personnel

to programs like ourselves.

Or there's, there's some sailing programs

or there's yoga retreats or, so they

have got, over the last 15 years got

so much better about using these more

holistic wellbeing programs for them.

Rupert Isaacson: But you are dealing

with people who are, as you say, in this

transition obviously you are dealing

with serving military as well, but when,

when people are in this situation where

a change is being forced upon them and

they're wondering like, Jay was what's

going to be my place in the world?

Mm-hmm.

Now Jay was lucky of course that he

knew that when he met you all, that

was gonna be a vocational step for him.

Do you get other military who then

want to come and work with you?

Have you then added them to your team

and what do you, you obviously you

can't do that with everyone, so what.

Do you guys do in terms of helping

people to look to the next stages?

Emma Hutchison: I think so.

So when the guys who are serving come

to us, they're either transitioning

out or they are trying to get

themselves well enough to stay in.

Now a lot of them will come here thinking

that they want to stay in because that's

all they know and they're terrified

of going out into the civilian world.

And then when they come here and they

meet some of the staff, hear some of the

stories meet our mentors because we have

mentors on our military programs, have

been through the whole process themselves.

And we just kind of talk about these guys.

They've all got amazing transferable

skills that they don't understand.

They don't realize what they're capable,

what they've learned to, you know, some of

these, the submariners, for example, are

crazy what they, engineering wise, they

know, and yet they think, oh, but how am

I gonna get a job in the outside world?

Well, of course you are your

highly intelligent, super talented,

got all these qualifications.

Of course you're gonna get a job.

You just have to have that confidence

to go out there and sell yourself.

And that's what these

guys are not good at.

They don't the ones coming

to us generally, it's

confidence, it's self-esteem.

It's, it's, it's those kind of issues

that they just need to be, we kind of

say that coming here is a reset button.

And if by coming to us for a week

just allows them to, to put their

life on hold and stop all, everything

that is spiraling outta control.

The fact that they are in a recovery

program that they have been flagged

up by a recovery officer, that people

do know that they've got mental health

issues and they're still serving, that

in itself is a whole kind of issue.

So come here, press that stop

button and don't think about that.

Just be with these, these other people

who are going through the same thing.

Everybody, again, you kind of sit

around the table and as Jay sort of

touched on with a physical injury,

it's very easy for people to say, oh,

I understand why you are here because

you know, you're, you're missing an arm

or you're missing a leg, or whatever.

It's, but when they sit around the table

and say, I dunno, I, I don't, I'm, I

dunno if I'm allowed to be here because

I've just got PTD or I've only got this.

And within 24 hours they stay

at a house because our military

program is a residential program.

They stay at the house and they,

they, part of the whole thing is that

they have to cook meals together.

And they have to say,

right, who's gonna cook?

Who's gonna do the dishes,

who's gonna clean up?

And these conversations are led

by our mentors and they just

start to find out, well actually.

I'm, this happened to me.

Oh, enough, same thing.

Something similar happened

to that person over there.

So they are able to then, because

it's, for some reason they can't talk

to families and friends about it.

Military, they're a funny bunch.

They, they just, you know, they keep

together, they keep closed up, but they

can talk to each other about stuff that

they can't, us civilians and outsiders.

So the, so the military programs

is residential because they

come from the whole of the uk.

So it had to be residential.

It includes the horses,

which they do in the morning.

It includes the other things.

So the bushcraft, the photography, the

breath work, the archery, the Pilates.

It includes all of those other activities

that we do in the afternoon because we

have to do something in the afternoon

because they can't work with the horses

all day and they can't go home because

they've come from Devon or whatever.

So that's why we, we started off

doing these other activities.

And then what we found is that in actual

fact, somebody does Pilates for the

first time and then says, my goodness,

I'm gonna do this when I go home.

So you've given them something that

they can then take home because

we can't give them a horse to take

home, but they can take breath work

or the archery or whatever it is,

and go, actually I'm try do that.

So.

Evening, sitting around the campfire,

talking to each other, cooking

food together, opening up, having

the conversations and laughing.

And the difference between when

these people arrive on the Monday

with their kind of shoulders

down and their no eye contact.

And,

and then by Wednesday the shoulders have

started to lift the, you start to get

the eye contact and then the whole yard

turns into this before and swearing and

banter and, you know, the, the competition

between the Army guys and the Marines

and the Navy and difference between

the tri services and things like that.

It, it's just phenomenal.

But as I say, it's a combination

of, of all of the stuff that

goes into this course that works.

Rupert Isaacson: I'm, I'm

intrigued that you use photography.

Mm.

How did that evolve and what,

what do you observe that giving?

Emma Hutchison: If I'm honest, we were

just looking for another activity.

Mm.

And we happened to have somebody

that was very good at photography

and we've all got these phones.

Yeah.

Nobody knows.

And they've all got these amazing

cameras in them and nobody knows

you take a photograph, nobody

edits them or does anything.

I was completely unaware of all the

things that I've got on my phone that

I can do to improve the photographs.

And so we literally had somebody

come and teach us our staff and run

some sessions with the courses and

it was an absolute game changer.

And some of the photographs

phenomenal.

So something.

But has actually become quite

a popular other activity.

Rupert Isaacson: Well, the reason

why that really intrigues me and as

you know, like with movement method,

we have that, you know, as well as

horse by method and ta So we're always

saying, don't just do horse stuff.

It's not enough.

You know, you've gotta, as you say,

send people home with other things.

The photography that you're

talking about intrigues me because

I can see how that's hunting.

Its stealth and capture,

it's also perspective taking.

You know, you have to look from outside

the situation into the situation.

It's also changing the situation because

you can take an image and that image

can also be emotional, internal, right?

And then you can rewrite it.

You can say, well actually no, I, I

think I'd like to edit that outcome.

And I think there's a subliminal message

that can come with that, which is to

say you can actually reedit your past.

You, you, you don't have

to say, this is my story.

If it's no longer serving you or if

it's too painful, you, you can work

with that story and you can rewrite that

story and you can affect that story.

And you, you can turn out 25

versions of that story with, you

know, through different filters, all

of which serve different purposes.

And I can, I could see how

even if you didn't make it.

Explicit in the language when you

were talking through the photography

skills, how that could come across.

So when you said photography,

my ears pricked up.

I was like, Ooh, I think I've

gotta nick that for our program.

Thanks Emma.

Because it's

Emma Hutchison: really simple because

you just go to wherever and we do, we

take them into the woods or we take them

down to the, the stream or something

and just say, well, what do you see?

And they, everybody sees different

things and you'll get, some of them

will be lying on the ground, taking

a photograph of a stone or a leaf.

Somebody else is talk, reaching up as tall

as they can to take things in the trees.

Or somebody's seen a rabbit

or a stone or whatever it is.

Everybody sees the same thing differently.

And so you come back with all these

amazing photographs from literally

just standing in a small area.

Rupert Isaacson: Have you,

have you collected some of

these photographs together?

Do you publish any of them

or exhibit any of them?

Emma Hutchison: Our to-do thing,

we keep saying we must do it.

We have got some great photos.

I

Rupert Isaacson: wanna

go to that exhibition.

Yeah,

Emma Hutchison: yeah.

No, we must do that actually.

Rupert Isaacson: You know, I was thinking

you could even make that in your arena,

like, constantly changing art exhibition.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: You know, of like every

few months you perhaps change, change it,

and then you could publish and sell those,

those those images images of transition.

I love it.

Note to self, have this conversation

further with Emma and let's

see what we can come up with.

It's so inventive what you're doing.

I love it.

Okay, so you don't, of course

just work with military.

You've pivoted to schools,

you've pivoted to adult mental

health and that sort of thing.

What precipitated that change?

Because I, again, I know quite a

lot of programs that are veterans

programs or first responders programs

that really stick very much with that

population because it is a fairly

specific set of experiences that

have brought those people there.

Again, I was really intrigued when I ran

across your program saying, but hold on,

they're doing all these other things too.

How did that evolve?

Emma Hutchison: So we started

with the military for the

reasons that I've spoken about.

We are a charity, we

have to bring in funds.

And around about those times when

we started, there was funding

for military programs because

everybody felt this affinity with

what the guys were going through.

About five years into it, we were

talking to one of the guys from the,

the lead military charities and he

said, you have to get all of your eggs

outta this basket because this, this

pot of funding that there is at the

moment is not gonna be there forever.

And it is, it disappear quickly.

So you need to.

And coincidentally at the same time as

this happened, we were approached by

the headmaster of one of the secondary

schools up here who said, I have

got a group of 15-year-old boys and

we don't know what to do with them.

They are just absolutely outta control.

We dunno what to do with them.

Can we send them up to you?

So I kind of did that and

whatever, and of course the boys

said, absolutely send them here.

So we had this group of, of boys and they

were fundamentally lacking some sort of

alpha male input into their lives, really.

And one thing we do have here is

quite a lot of alpha male energy.

Yes, you

Rupert Isaacson: do.

I've been up that.

Emma Hutchison: Yeah.

So, which is

Rupert Isaacson: unusual in a therapeutic

riding at equine assisted, you know, unit.

'cause normally it's,

you know, 90, 95% female.

Emma Hutchison: Yeah.

So they sent these guys up here, and

again, it was absolutely transformational.

The, the boys were given some

boundaries, given some rules.

They were given some consequences

if they reacted or didn't do what

they were asked to do in a very,

you know, polite way or whatever.

They were told to run around

the arena three times.

And they soon, it sounds like

terrible bootcamp, doesn't it?

But it, it was just, they hadn't

experienced anything like that before.

And, after a few hours.

They loved it.

They loved that kind of release of energy.

When we work with the schools groups,

the first hour that we do with the

schools groups is not in a classroom.

It's not with the horses.

It's basically dependent on the weather.

If it's raining, it's in the indoor arena.

If it's not, it's in the outdoor

arena and we build obstacle

courses and we play around it.

So for the first hour that

they're hear the phones go into

a box that they're taken away.

And these kids literally, they

have to move because again,

children are not active enough

these days.

Yeah, I agree.

Emma Hutchison: They'll moan and

groan and whatever, but again, by day

two, they're absolutely loving it.

And you find out all sorts of things

about somebody who's actually really

accurate with a round of bat and

somebody else can catch really well

and somebody else can run really fast.

And yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: When you say that they,

the lads, your ex-military team, and I'd

like to talk, I'd like you to talk to

us a bit more about who you team are.

Obviously we've met Jay, but I've

met some of your other team too.

And I, I think it would be helpful for

listeners if you could introduce them

when they said, okay, go run around the

arena three times, you know, of course

some teenage boys might say, what f you?

And then of course it is not the

military, so you can't actually follow

up with any physical consequences.

So what did you just find that

simply taking that approach.

Was accepted by those boys because there

was actually this sort of need for it.

And the boys themselves, somewhere

from within knew that they needed

that or because, because that's

a risk to take, isn't it, to say,

okay, here's the consequence, run

around the arena three times, or

give me 20 press up or something.

And then the person says, well,

no, I'm not gonna do that.

And then you haven't really

got much to follow it up with.

So it's a, it's an

interesting risk to take.

Yeah.

So just talk to us a

little bit about that.

Emma Hutchison: This is

where Jay is an expert.

I have fallen to this a couple

of times where I have sort of

said there was one incident when

we had, again, a particularly

difficult group of teenagers here.

And we were all sat around the

you've got a kind of fire pit kind of

thing with a parachute over the top.

We sat there having a chat in the morning

and this kid was just constantly talking

and on his phone and I said, I'd really

like you to move because I'd like you to

move over there so that you're not next

to, and he looked at me and he looked

at me and he looked at me and I thought,

oh no, this is gonna go horribly wrong.

It's not gonna move.

And about 20 sort of 30 seconds,

we had this sort of eye contact.

And then my heart was going, and then

he suddenly stood up and he moved

and he went and sat down and my heart

kind of went down and I relaxed and

thought, I've got away with that.

But I came back to Jay and said, oh.

Said Emma never do that

without a playing plan B.

And I said, well, what

would plan B have been?

He said, you'd have left him sitting

there and you move everybody else.

So Jay has these plans when he's

working with the kids because he's

generally the one that works with them

in that environment where if somebody

doesn't want to do something, well

everybody else will move somewhere else.

And then that person is where they

are, but now they're not with their,

all their friends in their little

gang because their friends in their

little gang have moved somewhere else.

So then they want to be where

you want to be, so they're gonna

do what you ask them to do.

So it's not by force

or anything like that.

It's by not mind games even.

It's just clever skills that, I dunno

where he got 'em from, but yeah, he's got

these things all in his little toolbox

that he can manage to assess any situation

and, and get these kids to do this

without realizing that they're doing it

Rupert Isaacson: interest.

So interesting to me.

Okay.

Talk to us a little bit about the

other members of the team now.

I met taf for example.

When I came up, I met Jock.

Jock wasn't as around as I would've liked.

So I, I didn't get a lot of time

with him when I was with you.

But I could see, you know, extremely,

extremely charismatic man with bringing

his own ex-military experience.

Just talk us through a little

bit the team you've got.

'cause it really is unusual

to find such a male.

Presence in an equine assisted team.

Emma Hutchison: So Jock, my husband

so he basically was a Royal Marine

commando and a helicopter pilot

in the military for 10 years.

So he also has had a passion

for horses since he was a child.

He has a DHD.

He can't sit still for

more than 15 minutes.

That's on a good day.

He is absolutely passionate about this

type of work, about helping people.

He's been through his own kind of mental

health issues and so feels really empathy

for those that are going through it.

And he, his huge skill is being

able to connect with people on that.

First, they come up the drive and

you've got him in his cowboy hat

and his chaps and his horse kind of

saying, hi, come with me and I'll

just talk to you about me and my horse

and the relationship that we have.

And he's able to, within that 45

minutes to an hour, be able to get

somebody to say, wow, this is, this

is a place that I want to come to.

I understand that I, I too

could have a relationship with

a horse and with another person.

And I, I, I do it annoyingly

with, with anybody who here.

Whether it's autistic kids, whether

it's military guys, whether it's

Wi Ladies, whether the whole, he,

they come and they just think that

Jock is the best thing since Slice.

He then hands them over to us and

it is almost like his, his bit, his

kind of showmanship, which is his his

main kind of role is, is, is done.

And then we, so we kind of wheel

him in and wheel him out as and as

and when he's needed because he's

amazing for these other things.

But again, the energy with Jock can

be quite high because that's what

he's, so as I say, we have to wheel

him in and then wheel him back.

But again, he does all the PR stuff and

the marketing stuff and things like that.

And he's a very good ideas person.

So he'll come up with

these, what about this?

Why don't we speak to these people?

What about this, what about, and, and most

of the ideas you say, no, but every now

and then there's, there's one that you

go, Hmm, naturally if we put that thought

into that, we could work with that.

So that's, that's him.

We then have ta who runs our, it

was the Princess Trust program.

It's now the King's Trust.

So that's our Youth 12 week youth

development program where it's

for 16 to 25 year olds and they

come here for 12 solid weeks.

And throughout that time,

they work with the horses.

They do all the other activities

that I've already mentioned.

They have a week where they do, they

go out and do adventurous activities.

So they, we hire e-bikes for

them and we make them e-bike up

some hills and things like that.

They do river walks, they do camp out.

Which bizarrely bearing in mind that

we live in Aberdeen, she, a lot of

these kids have never stayed away

from home or let alone camped out.

So it's a huge deal for a lot of

these kids to go away on this.

And it, this is a residential week apart.

12 weeks is a residential program.

They do work experience, they do

I do that a community project.

So one of the community projects was they

went around one of the local estates and

they cleaned all of these old a hundred

year old well rest and be thankful things.

So when the old Drovers used to

bring the cattle and the sheep

along, they would, they have these

rest and be thankful water things.

So they cleaned all those

for community project.

They cleaned a load of tracks.

So it's an amazing project that they do.

Path is retired officially

from the military.

He's in his early sixties.

He was in the military for 40 odd years.

Rupert Isaacson: What did he do?

Emma Hutchison: He was in the

pioneers, so he was, he was in

as a noncommissioned officer to.

And then ended up

Rupert Isaacson: to ask you about

who the pioneers are because I,

that's quite an interesting branch

of the British military, which I

think a lot of American listeners

and some would not be familiar with,

Emma Hutchison: I think I'm

not a great expert on this, but

they basically build things.

So if you go somewhere and you need a

bridge build tool, something, whatever,

the pioneers of the people that go

in with the expertise to build the

bridge to get the tanks over, right.

So, he's a really charismatic guy.

He, the last few years that he was

in, he worked at the OTC, which is

the young officers in the university.

So working with young, young people again.

And he now runs this program and

he's absolutely amazing at it.

Yeah.

So you have taf, you have Joanne,

who's our admin lady who again

is married to an ex Navy pilot.

So again, you've got the

Navy connection there.

And then you have my daughter,

Charlotte, who you know, support

you through and through, she's

done a psychology degree, so she's

interested in, in all that side of it.

And then we've got Georgia, who

is one of our school leavers.

So she came on one of our schools

programs about four years ago.

She then came here on work experience and

she's now employed as a, as a yard person.

She's amazing.

And then we've got some guys down

south who, again, more ex-military

guys who when we are running programs

elsewhere, or they'll come up and

be involved in the, the program.

Are is,

Rupert Isaacson: are these the people

that you refer to as your mentors?

Emma Hutchison: No.

So these, that's our kind of southern team

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Are

Emma Hutchison: basically people who have

been through the program and then we have

recognized certain skills with them and

thought, Hmm, that's somebody that will

be amazing as a mentor for other people.

So we then put them on a mentors

and an additional program that Jay's

put together and they come up here

and they, they given, you know,

things about boundaries and, and

sort of additional skills to help.

And

Rupert Isaacson: these would be people

who transitioned out of the military

exactly as we were talking about earlier.

Gone through that identity crisis

and then have come out on the other

side of it and have created careers

and lives in the civilian world.

Emma Hutchison: So they have all been

through huge, huge processes themselves.

So they have got the empathy, but as

you say, they have, they still, they,

they would all quite happily admit

that they're still on their journey.

I think we're all on some sort of

journey, but they all happily say,

well, you know, some of them are

working others are, are not working.

We've got John, who is 79,

he's an ex Royal Marine.

He is the fittest,

79-year-old you will ever see.

And he's amazing.

And he said, this is what.

He up here four or five times a

year, and he's just brilliant.

So they're kind of like, you know, mom

and dad at the house dependent on age.

Rupert Isaacson: But that's such a clever

way to organize because I think a lot

of organizations like ours that, you

know, the manpower thing is, is massively

tricky because it's, you know, humans are

expensive and also entirely necessary.

Yeah.

And then you don't

always have so much work

for the whole team.

So to have these people that, you

know, are adjunct, that come in

and come out who've also graduated

through your program, I think

there's actually a lot that a lot of

listeners could learn from with that.

Because one of the, as you can

imagine, I go around doing a lot of

trainings and one of the things I

hear regularly is I haven't got the

capacity, the human capacity for the

amount of work I need to do, or that

is coming in and I can't yet fundraise

for all those full-time salaries.

And, you know, I can't necessarily

hire those full-time salaries

until I know that those people are.

Worth, you know, able to fully

integrate into this program because,

you know, and then they might be out

on a limb geographically like you are.

So that, you know, the equivalent in

the USA, they might be in the mountains

of Colorado or they might be, you know,

some of the places we have in Ireland.

And there's a difficulty because

people then have to relocate from

somewhere else to do that job.

And then you're taking a big risk,

you're taking a punt on that person.

And if it doesn't work out for whatever