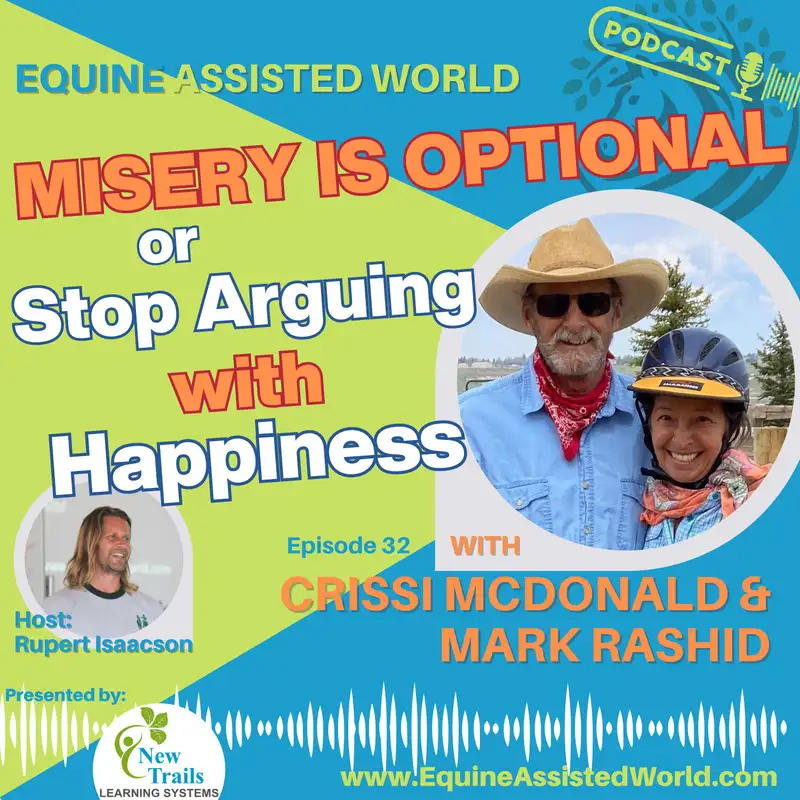

Misery Is Optional – Redefining Softness, Structure & Anxiety with Mark Rashid & Crissi McDonald | Ep 32 Equine Assisted World

Rupert Isaacson: Welcome

to Equine Assisted World.

I'm your host, Rupert Isaacson,

New York Times best selling

author of The Horse Boy, The Long

Ride Home, and The Healing Land.

Before I jump in with today's

guest, I just want to say a huge

thank you to you, our audience,

for helping to make this happen.

I have a request.

If you like what we do, please

like, subscribe, tell a friend.

It really helps us get this work done.

As you might know from my

books, I'm an autism dad.

And over the last 20 years,

we've developed several

equine assisted, neuroscience

backed certification programs.

If you'd like to find out more

about them, go to newtrailslearning.

com.

So without further ado,

let's meet today's guest.

Welcome back.

I'm here with the amazing

Chrissy McDonald and Mark Rashid.

Those of you who listened to our

previous podcast know that we ended

with talking about really how to

achieve softness and softness being

something that isn't just physical.

Of course that comes from within.

Mark was talking at some length

about his relationship with

Aikido, for example, and music this

way, not just with horsemanship.

Chrissy echoing many of these intimate

at the same time.

I became anxious and I thought, well,

if I'm becoming anxious, probably

other people are anxious too.

And the anxiety was, what

if I'm not soft enough?

And now we've gotta be soft?

Oh, now we've gotta be soft.

What if I'm not soft?

Ah, you know, and it brought to mind,

I think we live in a particularly

anxious society where in some ways

things have never been better, and

in some ways there's never been so

much to cause us to feel anxious and.

We've never taken, I think this idea

of fairness and ethics to heart,

particularly in the horse community,

in the way that we have now, it's, it's

definitely, I think, unprecedented really.

And at the same time, and that's

good and at the same time, it can

cause one to feel anxious, of course,

that one's not living up to this.

And, you know, should

we do anything at all?

Should we even go near a horse?

Should we even put our fingertips

on a horse, let alone our butts?

You know?

And should we put anything in

their mouths, let alone, you know,

anything on their noses or anything.

Or anything or anything.

And that spiral of anxiety,

of course is not soft, but

we're in pursuit of softness.

So there's a paradox there.

And I'd like to explore that paradox.

'cause I think we're all, to

some degree battling with this,

or at least dancing with this.

And when we have people like Chrissy

and Mark who have good, incredible

things to say on these things, I

think it's worth bringing this up.

'cause I do think it's a, it, it's a

concern not just for horsemen, but for

people who are running programs at equine

assisted programs, that sort of thing.

We, we want to, we want not

just our horses, but the people

we're serving to have agency.

And at the same time, this can

cause anxiety where we end up

trying to control that anxiety.

And so what do we do about that?

What do we do about that guys?

Mark Rashid: Well, I'll jump in.

Basically, the idea for, for

us, when we talk to folks is

oftentimes, especially when we're working

with horses and with people, is that the

idea is to be as soft as you can be, which

may not be as soft as you want to be.

And you know, as, for instance, on

a scale from zero to 10, with zero

being no pressure, you know, as

soft as I wanna be is maybe a 0.5.

But given the circumstances of the day

and the situation that I'm in, I might

have to go to a seven, but that's as

soft as I can be on that day, in that

situation, the key to that is that we

don't bring emotion into the situation.

We're just dealing with

what's in front of us.

Without making up stories around what

we're, what we're dealing with or what's

going on, just deal with the situation.

And then with, if you can, I

mean, working on internal softness

is, is really important I think,

and we can talk about that too.

But, but a big part of it for me is being

able to control self, having self-control.

And I think that's where, where we get

into trouble sometimes is that we we're

trying to be soft, but maybe things are

escalating and, and now I am, I'm at a

seven and I'm outta control emotionally.

I'm angry or I'm scared, or, or whatever.

And, and it's difficult for situations

like that to come back into control.

So for me, it's not so much about being,

you know, we talk about being soft.

The goal might be to be at a 0.5

in everything that I do.

And I also have to understand that

there may be times where I may have

to, because of the situation, I

may have to bring that level up.

And so that's, you know, that's kind of

the way that I would, I would, that's a,

I mean, for, to start the conversation.

That's, that's what I would,

that's what I would offer.

Rupert Isaacson: That's it is

quite intriguing to have a scale

that one could put a number to.

Is that an Aikido thing or is

that something that you've just

come up with instinctively?

I.

Mark Rashid: I've pretty much

come up with that just in our

teaching with horses and riders.

Mm.

Just so that we have some language and an

idea to, you know, if we're using a scale

of pressure, for instance, on the reins

with a rider, I can maybe get on one end

of the reins and the hor and the rider be

on the other while they're on the horse.

And I could say, well, could you show

me what a, what a one feels like to you?

And, and then on, you know,

feeling what they do in the range.

I can say, well, that actually

feels like about a three to me.

Let me show you what a, what a one feels

like to me so that we can, we have a

jumping off point and so we, we can be

speaking the same language instead of,

instead of some arbitrary, you know, speak

that, you know, we, I may understand as

one thing and the rider might understand

as something completely different.

So it's just a, just a way for us

to kind of get on the same page

and have a jumping off point.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah,

that's helpful, Chrissy.

Softness and the anxieties around it.

Yes,

Crissi McDonald: yes.

So the first thing I thought about was

because we're talking about softness

as an internal state, and we're talking

about the paradox of also being anxious

and having that be an in internal state.

I completely agree with you that I

think these times and our cultures

have a lot of anxiety right now, so

it's really easy just to be anxious and

it takes practice to not live there.

One of the things I like to talk about

is anytime we have something going on

inside of us, it's like a speed bump.

So I get up in the morning and I

look at my email and there's someone

who's mad that's a bump, right?

And then I come out and

I check on the dogs.

Maybe one of my dogs isn't doing good.

That's a bump.

And then I looked at my texts and then I

look at social media and then, you know,

you can see how this starts to snowball.

Yeah.

And

Crissi McDonald: so by the time I get to

my horse, I've maybe driven in traffic.

I have dealt with other drivers.

Maybe I listen to the news,

which isn't that great right now.

Maybe I've seen an animal on the side

of the road that got hit by a car.

I mean, it, it's just

that this is life, right?

It's messy.

And so by the time we get to our horse.

We're not traveling along

a smooth road anymore.

We are constantly going over

these speed bumps internally.

So I think the practices is when you,

when tho when that information, when life

hands you these things, is to be able to

be aware of it, recognize it, and then

try to get yourself back into homeostasis.

So meaning you're not too, you're

not in a panic attack, but you're

also not almost falling asleep.

Right?

Your nervous system, from what I

understand, I'm not a therapist, but what

we're learning from a friend of ours is

your nervous system is meant to do this.

Right?

We don't, I was under the misconception

that I always had to be parasympathetic.

I always had to be calm.

And anytime I felt a blip of

anxiety that was bad and I had

to do something to take it away.

And that's really not a complete picture.

So I'm learning more about the nervous

system states, but before I started

learning about this, every, I would

think about the inside of me as as

how many speed bumps have I gone

over before I got to my horse, and

how can I smooth that road back out?

Because every time we have a

speed bump, that's a, the horse

is trying to communicate right?

And it can't get over that.

So it hits this, this

is my feeling, this is.

Is a feeling I have.

We're working with our horses.

We're maybe in a certain state, but

we're so tight internally, maybe

we're trying to be soft and we

just can't be soft and oh my God.

Now I'm not soft in my, I'm

torturing my horse, right?

Rupert Isaacson: I'm torturing myself

with this or torturing die for softness.

Yeah.

Crissi McDonald: Yeah.

But if we could take a breath

and just let all of that go.

Just, just, we don't have to let it go

in the sense of, I'm never gonna think

about it again, but can I just set that

aside for 20 minutes and be with my horse?

You know, I'm not ignoring

it, I'm not bearing it.

But can we kind of let that pass

through us instead of sticking inside?

Can I let that information pass

through me instead of getting stuck?

Rupert Isaacson: Now, let's say you

have a mechanism, and let's

say it's breathing for that.

And you arrive at the place where you

keep your horse because not everyone is

lucky enough to keep their horses at home.

And then you come in and perhaps

you see a face that causes you some

anxiety or someone enters the arena

that causes you some anxiety, perhaps.

Your horse is living in a box.

And has been stood there for a long

time and is full of energy to be

expressed and can't be soft because

just can't be soft at that moment.

So one's own desire for softness,

of course, is unable to be met

by the horse in that moment.

And now I'm anxious about that and I'm

anxious about these other people and

I'm anxious about, and I'm anxious about

breathing will certainly help

me, but I suspect it probably

won't get me fully there.

When we are dealing with all these

imperfect situations, we are assuming

that not everyone is living on their

own private ranch in the Rockies

backing onto a national forest.

What are some really practical things?

Breathing for sure is one, but what

are some really practical things we can

do to try and access that softness and

particularly when the horse is not meeting

us with softness and can't in that moment?

Crissi McDonald: Well, I'll throw in

my 2 cents, then we'll go to Mark.

I, I find a really helpful thing to do,

especially if a horse is coming out of

a stall, is instead of having an agenda,

I am gonna do these five things today.

As we bring the horse out of the

stall and see what the horse needs

that may be to go for a walk.

Mm-hmm.

It may need if there's turnout.

Mm-hmm.

Crissi McDonald: It, part of

softness is also awareness.

So we look at our horse and we say, okay,

this, you know, whatever the situation

is, this is where my horse is right now.

Mm-hmm.

How about we, I'm a big fan of doing what

you can do, not doing what you can't.

Mm-hmm.

That's good.

And I got

Crissi McDonald: that from a certain guy.

So what can we do on a day when a horse

is much bigger than we would, you know,

we look at 'em and we think, I'm not

ready to ride that, but what can we do?

We can go for a walk, we can lunge, we can

find a round pen and explore some things.

We can turn out and let our horse great.

I mean, there's, so we get so

focused on what we can't do.

I think, I think that's a survival

bias or something Steve would know,

but we get so focused on what we can't

do that we lose sight of what we can.

Mm-hmm.

And there's always something we can do.

Or I mean, even, even if we just spend an

hour walking our horse around the property

and the horse ends up feeling softer,

less worried, that's, that's a good day.

That's quality over quantity.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Crissi McDonald: Right.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah, I agree.

Crissi McDonald: That's,

that's my thought,

Rupert Isaacson: mark.

Mark Rashid: Well that's, I, I think

the, the question really needs to be

how do I get into a state where that

those things don't bother me so much?

And you know, for me, I, I, I try to

live my life in a certain way to where,

to where I don't get anxious very often.

That doesn't say that I don't, but

I, it doesn't happen very often and

most of the time it's just one of my

practices is to look at things for

what they are and not worry so much

about building stories around things.

And, and, you know, that's, for me,

that's been a really important step

in not just horsemanship, but life in

general, so that not everything has

the same level of importance, you know?

So, forgetting the milk

at the grocery store.

For a lot of folks has the same importance

as getting into a fender bender in

the parking lot of the grocery store.

You know, or, you know,

it's, it's unbalanced.

It's an, for me it's an

unbalanced way of being.

Hmm.

And going through the day.

So, you know, being able to see things

for what they are instead of, you

know, taking everything so seriously.

There are some things that need

to be taken seriously, but you can

still do that in, in a calm state

of mind from, from an internal.

So for me, the, the, it starts

with how are we living our life?

Because, you know, you made a really

good point in that we basically

live in a low level state of panic.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Mark Rashid: You know, I'd say that's true

Rupert Isaacson: for most people and

Mark Rashid: be, and that's, we

allow that, that's a choice we make.

So, yeah.

I mean, the world is what the world

is and our, you know, it's like,

like Chrissy mentioned, you know, the

news, watching the news, well, there's

nothing I can do about any of that.

You know, I, I can't, there, I

have no influence on any of that.

Yeah.

At all.

And so, you know, I can't

let it bother me too much.

I.

You know, I have, I have influence

in the, in the three foot

space around me more or less.

And so I feel like that's

a good place to start.

Rupert Isaacson: That's

stoic philosophy basically.

Mark Rashid: Hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: Which interestingly

they say was started by a man called

Han who happened to be a horseman.

Hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: And a student of

Socrates and the best mate of Plato.

And also a mercenary.

Just,

Mark Rashid: you know, it's funny,

it's funny because, you know, in

the dojo we spend a lot of time, in

fact I'm, I'm doing a an upper belt

class that, that meets once a month.

And in that class, what we are working

on is being able to stay in a calm state

of mind, regardless of the situation,

regardless of the type of attack that's

coming, regardless of the weapon that

the person is holding, regardless of, of

how many people are, are surrounding you.

And again, it's a practice and we

just don't practice those things

and we get good at what we practice.

And so if we practice being in a,

in a worried state of mind all the

time, this low level state of panic,

then we're gonna get good at that.

And if we choose not to do that and we

choose to practice something else, then

you know, then we'll get good at that.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

I mean, I think many of us grow

up being trained to be anxious.

Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: Because, yeah,

that makes us controllable.

If you're anxious about your grades, if

you're anxious about not getting punished,

if you're anxious about going to hell,

then you could be manipulated quite well.

And of course, I think many of us

did grow up to some degree that way.

So the unlearning of that is tricky,

particularly when you are being bombarded

with anxiety in, you know, amygdala

triggering media that deliberately is

there to trigger you because it makes

you keep watching and keep clicking.

And of course, what could be a better

partner to help us with that than a horse.

But we found, I, I, here's

an interesting thing.

When I moved to Germany back in

2018 it was the first time that

I had not kept my horses at home.

And because I arrived with six horses

and I didn't want to kind of, and I

couldn't just like arrive and buy a farm.

And I had to wind things

up in Texas and so on.

That takes, took a while.

And anyway, it was would've

been, you know, a massive schlep.

So I thought, well, let's just keep,

let's just downsize, let's just keep

the horses, you know, at a boarding

barn for a while while we find

our feet and look around and Yeah.

You know, be less stressful.

And so you got there,

you gotta look around.

And so, okay, well where do I go?

Where I can arrive with six now?

I don't wanna spread 'em out

all over the countryside.

That's, yeah.

So that narrowed the choices.

And then we ended up at a place and not

too far away and dah, dah, dah, dah, dah.

So that narrowed the choices again.

And then we ended up at a place where,

well, they're gonna live in boxes.

And when I was a kid growing

up, our horses at home, we did

have 'em in boxes overnight.

In the winter you'd bring them in, 'cause

the weather's pretty rough in that part

of England and I, but you'd let 'em

out again in the morning right away.

And these were horses that were

in either high competition work

or hunting horses or whatever.

So it's not like they were not clipped

and not doing, but they were clipped.

But you put rugs on them, you

kicked 'em out for the whole day.

You brought 'em back and

it's just what you did.

And then I was like, oh, well

no, we can't do that here.

Even though there's all these

fields, because the German

farmers don't like muddy fields.

They don't like to see the mud.

Like, oh, oh, that's old coming

from the uk because we like assume

everything's gonna be a mud bath.

Alright.

Okay.

And then I rose, wow.

My horses are not gonna

get out in the winter.

Like, yeah, they have like a

place they put 'em where they can

stand around for a couple hours.

It's not the same, right?

And these horses have to now give

wellbeing to these autistic kids

who are coming and so on and so on.

And they're just gonna be

standing there going stir crazy.

What can I do?

And so I thought, well,

crazy, that's the word.

If the horses are going crazy, then

they need to express that craziness.

So we came up with this thing called

crazy time, where I would take them up

to four of them into the covered arena at

one time and just set up obstacle courses

for them of any kind I could think of.

They liked to jump, so that included

jumps, but it wasn't just about jumps.

And I'd let 'em go and they'd go bananas

in a, in a group and for a while and do

it all and kind of then turn and look at

me like, and now, and I go, oh, I see.

They want that interaction.

So then I would change it

and then I'd say, off you go.

And they go banana for a bit and

then they'd turn around, look at me.

And then that all you got.

And then I, we, so we evolved this

pattern and then I was thinking,

yeah, but how do I, they science

me quite a lot at this crazy time.

And then after that they

got so many endorphins.

They're actually quite happy

to stand and chill for a bit.

But then of course the

regular work starts.

But this is time consuming.

And I thought anxious

again, right Time conflict.

And that's said, well,

hold on, hold on, hold on.

Why don't I get my kids

to do the crazy time?

Why don't the clients come and do the

crazy time with the horses and, oh, this

is good horsemanship and you know, team

building, gotta build the thing and so on.

And then, oh, but now I'm under

pressure because I'm also supposed

to be teaching these kids stuff

like maths and things like anxiety.

I'm like, well, hold on, hold on, hold on.

How long is the wall of the arena?

Let's walk it out.

Oh, it's 60 meters long.

Okay.

And how long does it take that

horse or that kid or that dog to

make it from one side to the other?

And can we do distance over time?

And that gets you speed.

And suddenly I realized I'd stumbled

into this massive teaching tool

that everyone's needs got met.

And it happened because I had

ended up in this really imperfect

situation, got very anxious about it,

the horses kind of showing

me what they needed.

What was interesting was

after I then left there and went

back to keeping my horses in a more

naturalistic way, which I do now

again, I realized that I should have

been doing crazy time the whole time.

That they really, really dug it like I had

been of the, of the opinion that, well,

if they turned out, that's kind of enough.

But, but actually horses are

so playful and they love this

interaction with their monkeys.

That had I not been in that position

of anxiety, I wouldn't have, you know,

stumbled into this thing that, so I,

I do feel that anxiety can sometimes

be an aid if it's a temporary state.

And it's also interesting,

there's a slight contrast

between what you guys said.

You know, Chrissy, you were saying, well,

we're often taught that we gotta be calm

all the time, but actually we gotta let

our nervous systems fluctuate because

sometimes we're actually supposed to

react, you know, appropriately to things.

Jane Pike's work, I think is really

good at showing us that sort of,

for listeners who haven't gone and

checked out Jane Pike, go check out

Jane Pike and her nervous system work.

It's top notch.

But then Mark, there you are

talking about, yes, but I

need to be cool under fire.

I need to be able to think, I need

to be, not lose my ability to assess,

control myself, et cetera, et cetera.

Discern even under anxiety,

producing pressure.

Mark Rashid: Well, but those

are two different things.

Rupert Isaacson: Let's starts

with that paradox a little.

Mark Rashid: Those are

two different things.

Anxiety and pressure.

Okay.

Mark Rashid: So pressure will cause us to.

Caused our seek system to kick in.

So while you were, while you were talking,

I was thinking, was that anxiety or was

that pressure that he was feeling Anxiety

a lot of times doesn't allow us to think.

It, it true.

It puts us in a different state of mind.

Rupert Isaacson: That's the

amygdala and cortisol, right?

Right.

Yeah.

Mark Rashid: And so, but

pressure's a different thing.

Pressure causes the seek system to

kick in so that we search for answers.

So we look for a release.

So we, that's a different, it's

kind of a different ball game.

Anxiety.

I'm not, but pressure can

produce anxiety enough.

Enough, yeah.

Enough of it.

Yeah.

And without us being able to

deal with it in some kind of

positive and productive way.

So, for instance, you know, Dr.

Peters talks about, you know, in

the fifties they had a an experiment

where they put a dog on a, on

a metal floor in a little cage.

And the cage was split in two

by a, by a little wall that the,

that the dog could jump over.

And so they electrified the floor.

I guess a little light went on and

then they electrified the floor and

then the dog jumped over to the other

side where it wasn't electrified,

so it was able to get away from it.

And then they electrified turned the light

on, and that side electrified the floor.

The, the dog jumped over to

the other side and was safe.

And then eventually what they did was

they electrified both sides of the floor.

Okay.

And it, it, it was basically ended

up being learned helplessness.

So the dog just sat in the corner

and peed on itself and shook.

And, you know, which is one

of the reasons they don't do

experiments like that anymore.

But, but that's to, that's pressure to the

point where we can't deal with it anymore.

And the vast majority of situations

that we are in day to day don't

have that level of pressure.

We, we allow ourselves to

feel that much pressure.

But they, and that's kind of what I was

talking about before, is, does this situa,

is this, a friend of ours talks about it

in terms of, is it, is this a situation

or is this an, is this an emergency?

Crissi McDonald: Yeah.

Is it an event or an emergency?

An event or an emergency event.

Yeah.

Mark Rashid: And the problem is, is that

we see too many things as, as emergencies

when they're actually just events.

Hmm.

So that's very true.

So that's why while you were talking

I was, I was thinking, I wonder if

that was actually anxiety or if it

was, or if it was pressure because you

were able to come up with solutions

pretty quickly it sounds like.

Rupert Isaacson: Well, it is

interesting that what you were

talking about with which I said, well,

that's stoicism stoic philosophy.

One of the things that actually helped

me come up with that and it's, it's,

it's stoic saying, and I, I, I dunno

whether it's Epictetus or whether

it's Marcus Aurelius or both or

what or what, but it's one of them.

I think and I've often found this one

is really helpful when I'm freaking out,

is this doesn't have to be something.

It's only something if I make it something

mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: Which I

think could be qualified with.

This could appear to be something.

Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: But it may not be

something if I take a second look,

it's fair to say I think that many.

Horse owners and people in general have

been trained into over amygdala, you

know, anxiety, good work, where, as you

say, events are seen as emergencies.

Reading the stoics is helpful, and of

course meditation is helpful and so on.

But in people's day-to-day lives and their

day-to-day interactions with their horses,

what are some of the things that you

found have really helped you guys?

Because there must have been times

in your lives when you were a bit

more amygdala than you are now.

And what were the exercises that you set

yourself to go through that you found

cumulatively over the years have helped

you unlearn that way of looking at things?

Do you want, do you wanna

kick off with that, Chrissy?

'cause I know you've, you, you, you've

had your relationship with anxiety and so

on, so do you wanna lead with that one?

Crissi McDonald: Sure.

So the practices that I have mostly

have nothing to do with horses.

It is,

you know, I read all these articles

and it, and it always basically

comes back to good diet, good sleep,

good exercise, and good connection.

Hmm.

Crissi McDonald: So shaping my

life to prepare for myself in a way

that I can receive those each day.

You know, good connection, good

sleep, good nutrition good movement.

And, you know, I really enjoy reading

your books because they talk about

things as they used to be, you

know, people as they used to be.

You introduce us to people in

societies who aren't ours, and it's

a different way of looking at life.

But I feel that it's all

fundamental to all of us, you know?

Sure.

Wherever we live, wherever we're

born, whatever language we speak, we

need connection, movement, good food,

and you know, a way of looking at

the world that is more seeing it as

a whole, not just our little slice.

So I'm also interested in stoicism.

I like, I've read Marcus Aurelius

and Tic, I can never say his name

Rupert Isaacson: because I think there's

no one right way to pronounce it.

That's because none of us

really to pronounce that.

Yeah.

Crissi McDonald: So, so what that looks

like on a day-to-day basis is, you know,

I, I try to get as good sleep as I can.

I tailor my diet to my body's

needs, and we move a lot.

And then Mark and I are together a lot.

So that's the connection.

I keep in touch with friends.

This is a good connection

we're having today.

So this really is very nourishing.

Mm-hmm.

Crissi McDonald: And then by the time

we get to the horses, I'm already

so well resourced that if something

goes hap, you know, if something goes

sideways that I feel like I can manage

it, there are days when that is not the

case and I still have to go to work.

So on those days, the bar gets really low,

you know, can I be of service to people?

I may not be able to really work with

my horse in the way I want to, but can

I show up just for this eight hours?

Can I show up for myself and

for the people who are here?

So it, yeah.

Most of the practices have

nothing to do with horses.

It's, it's like what Mark was saying

before is how do we live our lives and

then how do we take that to our horse?

And I'm, you know, I'm saying this in

about five minutes, but act in actuality

it's been about 20 years that I have

put together this way of going or

this way of being that works for me.

And, and it's not as though

it got rid of anxiety.

I just have a less contentious

relationship with it now.

Right.

Crissi McDonald: Yeah.

And now, right now what I'm

doing is exploring creativity.

So I just ordered watercolors and

paints and paper and I've been

drawing and, i've been reading

about how creativity can actually

take, take us out of our amygdala.

So, and, and you know, all this

too, from your work with the

Rupert Isaacson: kids as Kima said,

for happiness, practice the arts.

Crissi McDonald: Yes.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Crissi McDonald: Yes.

So that's, I think that's yeah,

20 years distill down into

10 minutes before we, we, we

Rupert Isaacson: go to to, to Mark's

thoughts on this though, when you, you,

you run these intensives where people,

you know, come to you for 10 days

and so on, and these are horsemanship

things as well as life things.

So a lot of these people, of course,

are coming with anxiety because they're

coming outta the world that we live in.

So what are your, when, when you meet

them, you say, okay, for this eight

hours, here I am, I'm available.

What's your,

do you have some starting rituals?

Crissi McDonald: Well, the first

thing we do is we start in the dojo.

So there's movement and breathing.

And the major component of our time

with people is verbally and non-verbally

reassuring them that they're safe.

I mean, as safe as you can be with horses,

but it's creating an environment where

they are safe to express themselves.

It's the same thing we want for horses.

Hmm.

So there's joking and laughter and.

Reassurance and, you know, letting

people know that everything's

okay, that it's gonna be fine.

And then we have a meeting in the

afternoon and we've had several

meetings like this recently where we,

we'll go around and ask people what

we do like to do while you're here.

Mm-hmm.

And

Crissi McDonald: you can, you can feel

the anxiety, you know, my horse doesn't

do this thing and I didn't do this thing.

Or my horse, when he goes to

canner, he bucks and I've come

off six times and I broke.

You know, you go around, but genuine

Rupert Isaacson: concerns, right?

Yeah.

Crissi McDonald: Yeah.

And there's, you know, 12 people

there and, and you can just feel the

anxiety churning through the room.

Mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

Crissi McDonald: And it's really

interesting because then when it's

our turn to talk, you know, either

Mark or I'll say, you don't have to

ride today and you don't even have to

ride the whole 10 days you're here.

If you feel safe on the ground and you

and your horse are doing great, stay on

the ground it and, and the whole, you

can feel a whole room go, oh, thank God.

It's really, really interesting

how it's the pressure, right?

The pressure that then

we take into anxiety.

I have to, I'm here for 10 days.

I made the space, I paid the money,

and I need to get stuff done.

And what we come in and say is,

is it doesn't have to be that way.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

Of course you have that little

bit of anxiety in the back of your

mind going, well, gosh, I hope I

give these people value for money.

And you know, if they come here, you know,

am I going to give them what they need?

And you know, and I certainly

go through that Yes.

Clinic.

Yes.

I do

Crissi McDonald: too.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

How do, what, what do you do about that?

So every do my best.

You say to somebody look, you

don't have to ride, but you know,

they really, really want to.

And you know that if they go

away without having ridden

up, they will be disappointed.

And,

but it might be the right

thing for them not to not easy.

Not easy.

Yeah.

Crissi McDonald: But there are lots

of things we can do that lead up to

riding and it may end with them riding.

Yeah.

Right.

So we're not gonna, we're not

gonna say, oh, you have to work.

You know, you have to lead

your horse for 10 days.

Right.

Crissi McDonald: Let's lead your

horse and see how they do tacking up.

Let's see if, how you feel after you've

been breathing for a couple days.

Let's see.

I, I find in our 10 day clinics,

it takes about four to five

days for people to unwind.

Yeah.

And then the second week is when

a lot of the work that they're

wanting to do comes through.

It's, it's really interesting to

watch the dynamic of each group and

to watch that unwinding process.

Rupert Isaacson: I could see

how much of what you're doing.

I love the fact that

you started in the Dojo.

How much of what you, you guys

are doing is done out in nature?

And if so, what sort of nature?

Crissi McDonald: All, all of it.

We're outside majority of the time,

Rupert Isaacson: but there's outside.

There's outside, you know what I mean?

There's ki and you are there in Colorado,

so there's a lot of outside yeah.

For you to make, take advantage of.

Like how do you use the nature?

Mark Rashid: We that's an interesting

thing because the ranch that we work

off of, or we work out of is 115 acres.

And some of it's developed

and some of it isn't.

And so when I say developed, you

know, there's, you know, fenced

pastures and things are cross

fenced and, and but there's a ton

of trails on the, on the grounds.

And a lot of the folks that

come to us are struggling with

fear issues or some kind of.

Anxiety issues or their horses are, Hmm.

Or both?

We, I mean, we've had people whose

horses were really struggling and

the people weren't really that much.

They just kind of accepted that this

is how my horses and, and, and other

people whose horses were fine and they

were struggling and, you know, and

kind of everything in, in between.

And we just, we basically tell

folks from the get go two things.

One of the things that we say

is that misery is optional.

Okay,

Mark Rashid: that's cool.

So if you wanna be miserable, that's fine,

but you don't have to be so that we give

them permission on the very first day.

You know, if you wanna, if

you want to take the afternoon

off, take the afternoon off.

If you, if you're, if you need to

use the restroom, use the restroom.

If you're hungry, get something to eat.

Take care of yourself.

You wanna sit in the shade, sit in the

shade, whatever it does, that part of

it, you know, it's, it's your time.

It's bought and paid for.

You take care of yourself.

So we give them permission right off

the bat to, to just be okay being there.

There is, we don't have any there's

no structure to what we do in

other, well, there's a structure

if you want to call it that, but.

We, we work with each,

everybody as an individual.

We don't do anything as a

group other than ride together.

And we have a, a huge arena

and the arena's, I don't know,

maybe an acre or a half acre.

It's a huge arena.

And so one end of the arena is for people

who wanna, you know, do trot and canner.

The other end of the arena is for

folks who wanna do just walk and trot,

there's a round pen in the arena.

So ev you know, we, we can

keep our eyes on everybody.

And we tell 'em that you

can ride out if you want.

There's trails and a lot of the folks

will go out and hike the trails first.

Mm.

Mark Rashid: And then eventually they

might go out and ride the trails.

Mm-hmm.

Depending on how they feel.

There's a big loop around the, the arena.

It's on a road, but it's, you

know, it's kind of in the forest.

And a lot of the ri, a lot of the

people that show up who didn't think

that they would be able to ride out of

a, an arena, and by the way, the, the

arena doesn't have a fence around it,

so they end up going out and riding

that big loop either by themselves

or with other, with other folks.

So we, you know, kind of let

people get comfortable with the

things that they want to do.

In their own time with

our guidance, basically.

Rupert Isaacson: If you're in the

equine assisted field, or if you're

considering a career in the equine

assisted field, you might want to consider

taking one of our three neuroscience

backed equine assisted programs.

Horseboy method, now established

for 20 years, is the original

Equine assisted program specifically

designed for autism, mentored by and

developed in conjunction with Dr.

Temple Grandin and many

other neuroscientists.

We work in the saddle

with younger children.

Helping them create oxytocin in their

bodies and neuroplasticity in the brain.

It works incredibly well.

It's now in about 40 countries.

Check it out.

If you're working without horses,

you might want to look at movement

method, which gets a very, very

similar effect, but can also be

applied in schools, in homes.

If you're working with families, you can

give them really tangible exercises to do

at home that will create neuroplasticity.

when they're not with you.

Finally, we have taquine

equine integration.

If you know anything about our

programs, you know that we need a

really high standard of horsemanship

in order to create the oxytocin

in the body of the person that

we're working with, child or adult.

So, this means we need to train

a horse in collection, but this

also has a really beneficial

effect on the horse's well being.

And it also ends your time conflict,

where you're wondering, oh my gosh, how

am I going to condition my horses and

maintain them and give them what they

need, as well as Serving my clients.

Takine equine integration aimed

at a more adult client base

absolutely gives you this.

Quick thought, is being of service

to people itself a cure for anxiety?

Crissi McDonald: Oh, yes.

Mark Rashid: I would say so.

Crissi McDonald: Absolutely.

Absolutely.

Rupert Isaacson: And therefore, presumably

back to your point to one's horse as

well, showing up and okay, maybe I

can't do that thing I was planning

to do, but what does my horse need?

And if

Mark Rashid: a big, a big part of

what we do is that people will come in

with an agenda and we will help them

understand where their horse actually is.

And you know, these are, these

are maybe the limitations that

your horse has physically or

emotionally or whatever it is.

And then they learn how to deal with those

things, either with other professionals

that are on the ranch at the time.

We have a, an amazing holistic

vet that is there mm-hmm.

Most of the time when we're there.

And, is able to step in and

help people with their horses.

Rupert Isaacson: Is that is

just living there or comes in

specifically for your workshops or,

Mark Rashid: I don't know.

She's magical, so I don't,

she doesn't live there.

She

Rupert Isaacson: manifests out

of the birch trees, you know.

Yeah.

I mean, it's, it's,

Mark Rashid: she's amazing.

She is truly amazing.

She's just this little, she tries to

Crissi McDonald: schedule her.

Yeah.

She tries to schedule her

visits when, when we're there,

what's name, but she lives

what, should we be aware of her?

Crissi McDonald: Yes.

Her name is Dr.

Janet Varus.

How do you spell Far Hus?

Crissi McDonald: V-A-R-H-U-S-V-A-R-H-U-S.

Okay.

Crissi McDonald: Yeah.

I can give you her email

if you're interested.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah, I'd love to.

Sounds like someone I should be

interviewing on the on the show here.

Mark Rashid: She's pretty incredible.

Rupert Isaacson: Hmm.

Mark Rashid: But anyway, she does

have a tendency to schedule while

we're there and she rides with us.

She works on our horses and

we, and we trade out time.

So she comes to 10 day clinics, you

know, having worked on our horses.

We trade out the time.

And but yeah, she's, she's

just this little woman that

goes around and fixes things.

So, but anyway, that's part of the thing.

It's, it's, you know, it's not.

I think people come in, like

Chrissy said earlier, assuming that

these things are gonna happen and

then they're gonna feel better.

And what they actually do is they find

out that there are this whole other

set of things that don't have, don't

seem to have anything to do with the

things that they wanted to do, but

by the time they leave, they're doing

the things they wanted to by having

addressed all of these other issues.

Yeah.

So, you know, that's, that's kind

of our focus is, okay, what's

the, what's the real issue here?

You know?

And then is there some

way we can address that?

Rupert Isaacson: Is everyone

coming, coming with a quote

unquote dilemma or problem?

Or are some people just

coming for the crack?

Mark Rashid: Well, I go,

I come for the crack.

I know that.

No, I would say I would say there's

probably a majority of, I would say

if we have 10 riders, I would say

maybe eight of the 10 might have

some kind of an issue that they're

have, that they're struggling with.

Rupert Isaacson: That has brought

them to you, that they've made the

decision to come to you because of this.

Right.

So interesting.

A lot of anxiety to some

degree has brought them to you.

Mark Rashid: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Yeah.

And,

Mark Rashid: and, and a lot of folks

come from overseas or they come

from the other end of the country

mm-hmm.

Mark Rashid: And they don't bring their

horses, so they ride ranch horses.

And so they're trying to figure

out maybe regaining confidence or

figuring out how to do transitions

cleaner or just improving their

horsemanship, that kind of thing.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

It's, it's, it's interesting I just

wrote down as you were saying that, that

we get into horses in the first place

because we feel they'll,

they'll make us feel better.

Right.

As, as children we have this,

this, this will answer a dream,

a need will make me feel better.

Mark Rashid: Or you don't

even, like in my case, I didn't

even know why I liked horses.

Exactly.

I just did.

Rupert Isaacson: Exactly.

But you do, but you think

this makes me feel better, the

presence of this Absolutely.

Visually there in the landscape.

Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: Then of course we

get into riding and training and

this and that and, and then we,

my God, that's sort of anxious.

It's good enough, it's not good enough.

And then, and suddenly this thing

that we got into in order to feel

better is making us feel worse.

And then you are there in service

to help 'em to feel better again.

In, in, in my position.

I do have that to some degree as

well with horse training, so on.

But with the, the work we do with autism

and anxiety and trauma, it's definitely

people coming in not feeling good.

And us saying, this horse and this

nature will help you feel good.

And then in the background,

having to work out yes.

But what aspects of it will,

and it's really interesting.

The, the reason I asked about trails

in nature was in another, another

thing that I was slightly forced into.

When I began doing the whole

horse boy thing, the property I

did it on had no infrastructure.

So there was no arena,

there was no nothing.

It was, it was just me with my

kid in front of me riding around.

And then later as the program

grew and we had to train quite a

few horses to do it, it's okay.

Arenas are useful there,

convenient when you have to do a lot

of things with a lot of horses because

that footing will be good even when

the footing outside is not good.

Okay.

So we can agree that an arena

can be a good thing, but an arena

also, I feel carries a certain

innate spirit of pressure with it.

And because you think about what

goes on in arenas, it's, it's

focused attention, isn't it?

And you also think the arena, like the

Roman Arena, gladiatorial combat people

being put to death, eaten by lions,

you know, highly stressful events.

And although I suppose if

you're the public eating popcorn

watching it, perhaps not.

And they butchered to make a

Roman holiday, you know, that

Lord Byron Bower, the dying Gore.

But I think inevitably, as soon as

you enter an arena, you feel this.

So we deliberately built our

arena, our covered arena in Texas.

'cause we needed shade, man.

'cause it was, you know

what Texas is like?

Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: So we built a cover,

but it was only a cover and it was open

at the side, so you could see into the

woods and the kids could like hop off

the horse and go off into the woods.

And then we realized we needed to build

trails that were circular loops because

we had kids that were runners and they

wouldn't run into a wall of ve vegetation.

They'd sort of would,

but they'd look back.

And so you could like position someone

there and, oh hey, how's it going?

And the kid would just run back to you.

Then when we came here, the amazing

thing about Germany was access.

If you see it, you can

ride it and walk it.

No one's gonna come with

a gun and run you off.

It's absolutely amazing.

I've never experienced trail

riding like this before.

Sometimes the weather can

be quite bad in the winter.

So, there I'm in the arena, but now

I'm sharing the arena with sometimes

rather grumpy German people who, and

then I'm thinking, oh gosh, now how am

I gonna keep this kid emotionally safe?

Well, I gotta get back out on the trail.

And then coming to the realization,

oh my gosh, well if autism is,

you know, the difficulty with the

relationship with the exterior world

auto, the Greek word for the self

autom selfism locked within the self.

What am I doing in this arena?

You know, I need to be out there where

planet earth is, where all the things

that this exterior world to the point

that now even with the dressage,

our entire thing is done in nature.

It's just like, we call

it dressage in nature.

It's like, I'm not saying we'll

never go into an arena, but it will

be this much of the time, everything

else that we'll do, even if it's

like the Pifi P pii, Tempe Changey

stuff, we're gonna do it out there.

And why are we gonna do it out there?

'cause it's gonna chill us out.

And the horses have a tendency

to go forward out there anyway.

But they're happy, we're

happy, we're engaged.

But without even as naturey as I am, you

know, without the kids kind of almost

forcing me into that position, I wouldn't

have come to the obvious conclusion.

I.

That, well, maybe it

feels better out there.

And then things like dressage, which

can sometimes make people feel worse

because of some anxieties that can come

along with them, you can allay that by

just going where you feel better and

and that, that's even allowed, you know?

So the fact that you're working like that

and you, you mentioned, I was intrigued,

mark as you were talking because you gave

this mental picture of the geography of

the place really well, of how the arena's

laid out, and then this loop around

it, and then these trails off from it.

And then how people might walk the

trails first and again, lay anxiety

so there's no nasty surprises.

You know, where you're gonna go, blah,

blah, blah, blah, blah, blah bum.

But we know that many horse programs

are not done like this in, in, in

fact I'd say that because of the

convenience of arenas a lot of

ings, I would say leaves one feeling

more anxious than one went went in.

And I've certainly had that experience.

Do you teach people, you guys,

how to clinic, do you teach people

how to use nature in these ways?

Do you send them home with like a

prescription saying, okay, lads, when you

get home, get outta that fucking arena.

You know, do this, do

this, do this, do this.

Like.

Have you put weirdly a sort

of a structure on that yet?

Because I, I, I think from

what you just described,

some of those people coming to your

clinics may not have that experience

at home, and they may not take that

back necessarily unless someone kind of

grants them permission to in a weird way.

Do you know what I mean?

So, yeah.

Do you make that explicit to them for the

homework when they, when they go back?

Perhaps?

Crissi McDonald: We don't have

anything specific like that.

I think that's a fabulous idea what we,

because of the nature of the property,

you know, it's, it's set within, we have

fields and we have forests, and we have,

there's a creek that runs through it.

Mm-hmm.

Crissi McDonald: And it's very long so

people can walk from one end to the other.

I, from my point of view, what my hope

is, is that by experiencing that and

making that a practice for 10 days, that

they will seek that out where they are.

And sometimes we have discussions

that, that elaborate on that, you

know, just, they'll say, oh, I have

to go back to the real world now.

Right.

Crissi McDonald: Well, this.

Isn't any less real

than the one you're in.

It's just there's been a space created

for you to explore different things,

and it was your choice to explore

different things that doesn't leave

just because you leave the property.

Hmm.

Crissi McDonald: So, we'll, sometimes our

discussions get into that realm, but I

really, I really appreciate what you're

saying about nature and I, I agree.

We don't spend enough time in it.

I, I, I feel very fortunate because Mark

and I get to spend a lot of time outside.

If you're with horses, it's what you do so

Rupert Isaacson: Well, if you

are getting out of the arena.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Crissi McDonald: Yes.

Yes.

I'll let Mark chime in now.

Mark Rashid: Well, like Chris, you

said we don't, we don't really do,

we don't really give people homework.

Generally speaking, it's a pretty

transformative experience for people.

Hmm.

Mark Rashid: That is not our goal.

Our goal basically is to help where we

can and, and hopefully then things are

better when they, when they go away.

So, so for me, the.

That is always my, that's always

the thing that's in, in the, in the

front of my mind is how can we help

here and what can we do to help you?

And we have assistant instructors

and every day we get together with

them at the end of the day and we

talk about, okay, who did we get to?

Who did, who did we get to today?

So, you know, we wanna make sure

that everybody gets, gets some

time with at least one of us.

But we, we basically just go from

one student to the next student.

We just rotate all of us through.

And so folks are getting maybe the

same information in a different way.

And so something that I might say might

not resonate, but somebody, something

that Chrissy says basically going in the

same direction might resonate instead.

And so, you know, and we, we

basically, we, we very seldom will

spend more than about 10 or 15 minutes

at a time with any one student.

Sometimes it'll be more than

that if they really need it.

But before we can then we'll move off

of them and go to another student.

And so they make it 15

minutes of instruction.

Then maybe another 20 minutes to work

on it by themselves where there's no

pressure from any, nobody's watching 'em.

They can just work on it on their own.

And then just maybe just as they start

feeling a little overwhelmed, somebody

shows up, one of the instructors will

show up, give 'em another 10 minutes,

and then they get to do, and so

that's kind of how it works with us.

It's very low pressure of any

kind really, other than the

pressure that folks are feeling.

But even that starts to dissipate within

the first few days usually, you know, plus

we spend the first three mornings in the

dojo and that just getting people back

in their bodies makes a big difference.

Rupert Isaacson: You said we don't really

have a structure, and then you said,

well actually we do have a structure.

And then you've, what you've described

actually does sound quite structured,

but what I think perhaps I'm getting

from that is what you're saying

is the structure is not presented

in a pressure full way.

Can you talk to me about

structure, how you got, because

without structure one is lost.

You know, everything does have structures.

Nature has structures.

How do you, what structures do

you have and how do you, have you

evolved them and how have you evolved

them not to feel pressure full

Mark Rashid: well, it's interesting

'cause one of the things we tell

folks is that softness without

structure is not softness.

Hmm.

I'm not sure what it is,

but it's not softness.

Mm-hmm.

Mark Rashid: So there has to be, even

with softness, there has to be structure.

So, you know, we can just say, you

know, how many, how many muscles

are you using to do to pick your,

your coffee cup off the table?

You know, if you're using more muscle

than it, than you need to use to

pick that cup up, you're not soft.

Right.

But you're, but there's, even if you're,

if you're only using the muscles you

need, there's still structure there so

that you can pick the coffee cup up.

Mm-hmm.

So that's the first thing is

that I, I couldn't agree more

that ev their structure and

everything, including softness.

Rupert Isaacson: Ooh.

And so, okay.

The structure of softness.

Mark Rashid: Yes.

Rupert Isaacson: Talk Yeah,

please.

More.

Mark Rashid: Well,

when we very first started this

conversation, one of the things that

you mentioned was, am I soft enough?

Mm-hmm.

Mark Rashid: And so people will

have a tendency to take that to

the extreme where they're not, for

instance, even picking their reins up.

Yeah.

Mark Rashid: Because they feel that's

being, that they're having, that's, you

know, so they put a big loop in their

reins, and that's them having soft hands.

But it's not, it's just they're

having a big loop in their reins.

Soft hands is, is the ability to pick

up the reins and feel all the way

through the horse, through the reins.

To me, the problem I think that

a lot of folks have is that

they either use too much tension

pressure, or they don't use enough.

And so instead of, instead of saying

to somebody, just turn your reins

loose, and then that's soft, that's.

Well, you might be soft, but there's no

structure there, there's no connection.

And then of

Rupert Isaacson: course, if you do move

your hand, it's like an amplifying wave.

Yeah.

By the time it does actually

hit the horse's mouth, it's

Mark Rashid: a big Oh yeah.

I mean, you've got so

much momentum picked up.

Yeah.

You know, you've got

three feet of rain there.

Yeah.

Mark Rashid: You gotta take

up three feet of slack.

You, it's gonna, you're just

gonna magnify the issue.

Yeah.

Mark Rashid: So, you know,

there are times where we'll say,

let's, let's shorten your reins.

Mm-hmm.

Mark Rashid: I'm not saying get in your

horse's mouth, I'm just saying get closer.

And then, like we talked about

earlier, we'll spend time with them

feeling each other through the

reigns with my, myself, maybe

on one side, them on the other.

And I can't tell you how many

times I've heard somebody say

that was, that was so subtle.

I I never knew that It could be that

subtle, you know, when, when we're

talking about a release mm-hmm.

For instance, and a release, a

lot of folks have been taught

to just throw the reins away.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

And in fact, that's effectively

what the word in English means.

Almost a complete letting go.

It's a deceptive word release, really.

Mark Rashid: Right.

But the release can be something

as small as feeling Mm.

The tension in a muscle.

Mm-hmm.

Mark Rashid: Relaxing a little bit.

Hmm.

Mark Rashid: And, but you can't do that.

You can't feel that if you aren't there.

Yeah.

Mark Rashid: You can't feel that ever

so slightly, that horse trying to relax

that muscle, just that little bit.

You can't feel it.

So that's when we're talking about

softness with structure, it's about

actually stepping in and, and becoming

part of the, part of the situation.

And that's why I think one of the,

the problems that, I wouldn't say

it's a problem, but it's one of the

things I think that folks struggle

with is that they, I think that, you

know, you're in a situation and what

you wanna do is you wanna keep the

situation at arms length and you're

outside of the situation, you're putting

yourself outside of the situation.

But by stepping into the situation

now you can become part of it.

And now you have some, you know, you

can offer some direction, you can, you

can help when you're in, it's really

difficult to do when you're outside.

Not sure if that answered

your question or not, but

Rupert Isaacson: it does.

It just raises some more

questions, which I'm gonna, yeah.

Chrisy.

Crissi McDonald: So I'll, I'll

go to the, I'll start with the.

Mundane, if you will, structure.

So breakfast is at eight,

dojo is nine to 12.

I was gonna ask

Rupert Isaacson: because I'm, you

know, I need to know what, yeah,

Crissi McDonald: here's, here's, this

is like the structure, right, of the

10 day clinic, and then we have lunch

from 12 to one, and then we're with

our horses from about one to three 30.

And then we have a meeting at

the end of the day and we talk to

everybody about what they learned

and what they like to work on the

next day, and we answer questions.

So that's the structure.

And Mark and I are pretty

good at keeping that.

The structure of the structure,

we don't often run over.

We keep things flowing through

the day so people can have the

experience they need to have.

But within that, there are a billion

permutations of what can happen.

You know, people could be in the dojo

for an hour, but then they need a break.

They could be in the dojo all

morning, but then they don't wanna

start riding right at one o'clock.

They wanna let their lunch settle.

So within the structure, you know, like

Mark was saying, desire is optional.

What that means is, is yes, we have

this schedule, but you are in no

way or shape or form required to

do every second of every minute

of every day of that schedule.

You know, the, we have 10 to 12 different

people, 10 to 12 different horses.

And so to me it's a lot like art.

You know, you.

Paint a picture and you have the

structure of the, the frame, right?

Or photography.

But you can put anything

you want on that canvas.

You can throw paint at it, you

can paint something like Monet.

So I think structure in some sense

allows us to be unstructured.

It's, I think Picasso said learn

the rules like an, like a pro.

So you can break them like an artist.

Mm.

I think that's the quote.

I really like that.

Mm, I do too.

We

Crissi McDonald: learn the rules

first so we can break them.

That's the, ah, that I don't know.

That's the joy in life really.

Rupert Isaacson: W when we we're

training people to do the work with

autism, say what, you know, what

we're saying often is, look, some this

kid frequent is coming in without an

understanding of top-down instruction

without, and feeling somewhat lost in

the world, including in their own body.

So if we impose structures on them

that make no sense, all that's going

to do is cause amygdala, explosions

and not gonna get us anything.

Right.

With someone who's already

amygdala's, already really active.

And then in the early years with what we

were doing, people often criticized us

saying, well, you guys have no structure.

And I was like, no, we do, we have a

lot of structure, but it's invisible.

Meaning that

my structure shouldn't

be the kid's problem.

Like you are coming to

have a therapy session.

Now, that's not a nice message

for a kid because that's saying

to the kid, you need therapy.

There's something wrong with you.

I've never yet met a kid

that said, I want therapy.

You know, I've met kids that

say they'd like to play.

So we call them play dates.

Mm-hmm.

So there's a, a structure right

there, which is to choose a different

language that sounds less shaming, I

don't know, or less shit, you know.

And then within that structure

we have these guidelines and the

first one is follow the child.

And there's kind of three

main ways of doing this, but

without that, you have nothing.

But that is a guideline that is

a structure that is a compass.

So, but of course, you know, following

the child might mean, say the kid gets

up on the horse 10 seconds and wants

down again, or takes three months to

get on a horse or never gets on a horse.

Doesn't matter.

What we're after is neuroplasticity.

We can do more than horses, but

if we use the horse, it's good

to use it in a certain way.

That seems to optimize it.

So here's the structure.

So I'm often trying to get

the message across that a

structure should be invisible.

Like for example, let's look at Mark.

Mark has a structure.

He's got a skeleton and he's also

got these muscles and he's got

these arteries and veins and nervous

system and a lymphatic system.

And things are moving around

in very kind of an ordered way.

But you're not really aware of that.

You're aware of Mark and, and you

have a sort of an emotional aesthetic

reaction to the entity of Mark.

But if you look at him again, you notice,

oh, he's got, look, he's got cheekbones.

'cause I can see a little shadow

under there and I can see that, you

know, his, he's got these two eyes

with a brow here and I become a

bit more aware of his structure but

only in sofar as it allows me to

interact with this thing called

Mark who can walk around and

show me what to do with a horse.

'cause if he didn't have this

structure, he'd be sort of weird.

Blobby Mark, who was sort of

organs displaced here and there.

Boneless chicken.

Mark Rashid: Boneless chicken mark.

Rupert Isaacson: Indeed, indeed.

Which, you know, maybe after

a long hot bath, I don't know,

bottle of whiskey, but yeah.

But the, then they also say,

well they need boundaries.

And I say, yeah, but people so often

forget that or, or seem to assume

that a boundary means a barrier.

Mm-hmm.

And

Rupert Isaacson: the problem

with barriers I've always found

is that they, they don't work.

I mean, you shut the door.

I can kick it down.

You get behind a wall, I can blow it up.

You build a fence, I can jump it

or, that's quite fun actually.

Or, and I can certainly.

Break it a window.

Mm.

Break that and probably hurt

myself at the same time.

So barriers almost invite the challenge

of, I wanna bust that because we have

this innate desire for freedom, but I

feel like a, a boundary is like, say an

epidermis, like this thing I've got, if

as I drink more beer, it expands with me.

When I go on the dry for a little bit,

it sort of contracts with me a bit.

If I cut it, it heals itself.

If I go out on a hot day, it will let

enough moisture through to cool me,

but if I go out on a cold day, it will

close off enough to keep my heating.

But it's very porous and cell membrane,

you know, and elastic to cope with things.

And

of course, in the horse world as well as

in the therapy world, we're often told no,

there are these very, very rigid rules.

And even within dressage, you know,

the, the first, they've got the training

scale, six point training scale.

The first one is rhythm.

Everyone agrees on that, blah, blah.

And then everyone forgets the second one.

The second one is relaxation.

It's like, where did that go?

You know?

Yes.

Where did that go?

Yeah, well, I can find it more easily

in the forest than I can in the arena.

So maybe,

maybe

Rupert Isaacson: it's there,

but it's certainly not there

without someone yelling at me.

So it's, it's, it's intriguing to

me that you seem to have come to a

somewhat similar conclusion where

you, you, you give a framework,

but within that framework you are

endlessly flexible and at the same

time you want to be of service.

So if somebody does come in saying, I'm

really having problems with my cancer

transition or something like that, you,

you do feel that sense of okay, well I

want to honor that need and desire and I

would like for you to leave after 10 days

feeling that you have the tool for that.

Dance me through.

I think, 'cause I think a lot of people

when they're trainers beginning in

this, what field as well as therapists,

they fe put a lot of pressure on

themselves to give that value.

And again, that comes from a good place

that comes from an honorable place.

But of course it puts on

more anxiety and more stress.

And so when you are giving people stuff

to work on and then going away, of course

as we know, sometimes they can work on it

in a way that can compound the problem.

And then you maybe come back

to them 20 minutes later.

You could find them in a state of

disorder or you could find them in a

state of, oh yes, I've achieved it.

You made it sound very easy.

It's not easy.

We know it's not easy.

So how do you, how do you do that?

How do you, how do you show somebody

something per perhaps, quite

complex, leave them alone for a bit

and come back and have faith that

Yeah, they've probably, they're

probably on a positive trajectory.

It's quite intriguing.

Please talk us through

it, how you do that.

Mark Rashid: For myself, I don't

let people get off the track.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Mark Rashid: So if I, for instance, if

I'm, I work with somebody for 10, 15

minutes during that time, I may explain

something and I will ask them if they

understand what I, what I explained.

They may say that they understand

they wanna please you, and the

their face says, I don't get it.

Yeah.

And I will oftentimes, I'll say that,

okay,

Mark Rashid: you know, in a, kind of, in

a, in a joking way, I'll say, well, I, I

heard you say yes, but your face says no.

So which one of these is, well,

I don't really get that one part.

Okay, all right, well, let's go over it.

Right.

And, and we explain to people

that it's important that if you're

not getting something, make sure

to let one of us know, because.

It doesn't help for you to be a

little bit lost, then get off track

and then, you know, and then we spend

three days trying to get you back.

But in general, what I will do is I

will usually we're either horseback

or on foot, depending on the day.

And so what we might work with

somebody, they say, they get it, looks

like they get it, they'll go off.

And while I'm working with

the next person, I will be

keeping an eye on that person.

Okay.

Mark Rashid: And if it looks like

we're getting off track, I will excuse

myself from this person and go back.

Or if there's somebody closer that

isn't doing something, I might, you

know, say their name, one of the

instructors, and then I will say the name

of the person and that's all I'll say.

And then that person will go

directly to that, that rider.

So, we have ways that we kind of work

around those things so that, so that

people never really get off track too far.

We try not to let that happen

too much if we can help it.

Yeah.

No, that's fair.

Chrissy.

Crissi McDonald: For

me it comes down to the

innate belief that we are all capable.

Hmm.

Crissi McDonald: And we can all learn.

Hmm.

I, I, I just, I have such

faith, especially people

who show up to our clinics.

They, for the most part, are so open.

They come, they wanna learn something.

Mm-hmm.