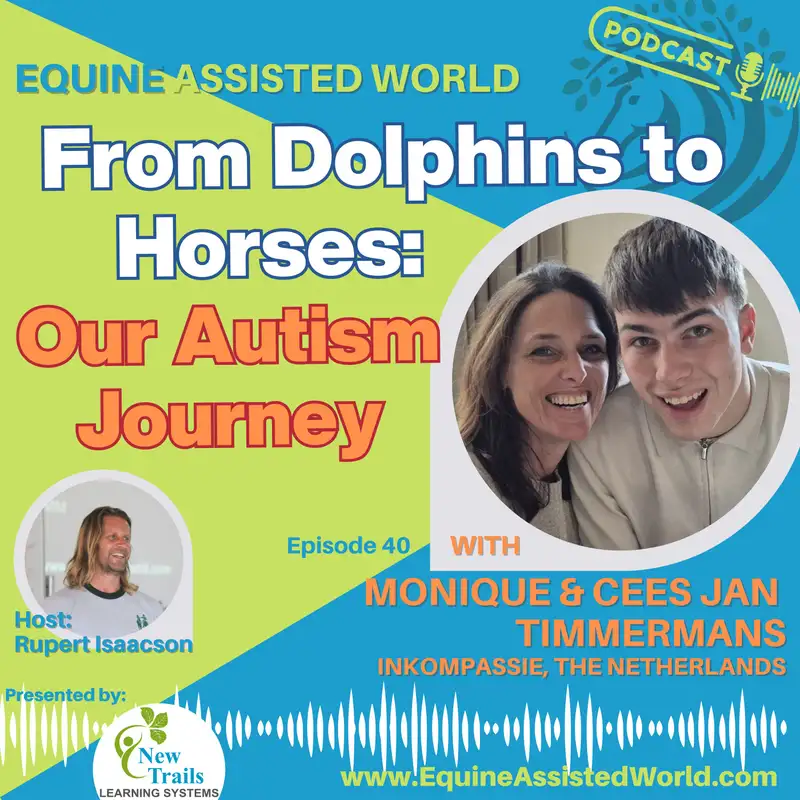

Autism, Dolphins & Horses: A Family’s Journey of Healing and Compassion | EP 40 with Monique Timmermans

Rupert Isaacson: Welcome

to Equine Assisted World.

I'm your host, Rupert Isaacson,

New York Times best selling

author of The Horse Boy, The Long

Ride Home, and The Healing Land.

Before I jump in with today's

guest, I just want to say a huge

thank you to you, our audience,

for helping to make this happen.

I have a request.

If you like what we do, please

like, subscribe, tell a friend.

It really helps us get this work done.

As you might know from my

books, I'm an autism dad.

And over the last 20 years,

we've developed several

equine assisted, neuroscience

backed certification programs.

If you'd like to find out more

about them, go to newtrailslearning.

com.

So without further ado,

let's meet today's guest.

Welcome back to Equine Assisted World.

Those of us who have family skin

in the game you know, everyone

knows my story with my son.

Some of you maybe have listened to

podcasts with the Berko family in Germany

and with Helena Helma and in New York.

And so all of us who are autism parents

or parents of kids with, you know, fairly

extreme special needs have a unique

perspective on this equine assisted thing.

Because we live it, we have no choice.

We're in it beyond the grave.

We have to turn our lives over to it

completely in a way that is perhaps a

little different to someone who wants to

get into it from a purely professional.

Or vocational point of view.

And so for that reason I'm always

very excited when I have parents

and families coming on the show who

have this experience and also have

created a practice, an equine assisted

practice from that experience because

I think we can all absolutely agree

that these people are the mentors.

So I've got a couple of these mentors

with us today from the Netherlands.

And their story with their son Stan,

has informed a whole practice in

a way of life which is now helping

people in the Netherlands and

through this podcast, perhaps beyond.

So without further ado I'm gonna

ask them to introduce themselves

and we'll take it from there.

So, who are you guys?

Monique: I am Monique Teman.

I am the mother of Stan.

And we also have another

son and another daughter.

So, that's me.

Husband: Okay.

I'm Ian.

I'm the father of Stan and our

other son, GU and our daughter.

And no, Stan is already now 20 years old.

Almost,

Rupert Isaacson: almost,

Husband: almost,

Rupert Isaacson: sorry.

Yes.

Almost 20.

Okay.

And you guys run an equine assisted

practice, Monique, I know you

are the main driver of this.

Yes.

Can you tell us a little bit

about what you do, and then we're

gonna go to your story with Stan

and how it's led to what you do.

So tell us about your practice.

Monique: Yes.

I have a practice where I do session

with people all kind of things.

And that's where I have the,

the, the beautiful colleague

of ever, and that's my horses.

Horses tell you everything you can lie to

them and they will put a mirror on you,

but they also can put your system on.

And then, I mean, a system who

can relaxing you, who makes you

zen, who puts on the nervous far.

We call about it.

And that's, that's when

it's going to happen.

And especially people with autism who

always are standing on, we, we call it

they're always beware of what is going

to happen, what was see, so all the,

the how do you call it in, in English?

The, the, the centering.

They, they will, they will put it in

and they, they don't know a way to put

it out and to, to getting regulated.

So, when I have someone with

autism and he's standing by

the horse, it's already there.

The horse takes the,

the, the extension away.

It's, it's, it's beautiful to see.

And the moment it's, it's happened

that's, the kids are, are the

people who is, who are standing

there, there, they, they, they have

right away another way of standing.

They are going to relax.

They feel their body, they are going

out of the brain into the body.

And that's, that's a beautiful thing.

So that's what I do.

And also take the old family

and holistic look at the family.

What is, what is happening with you?

What's happening with the parents

when you have a kid with autism?

What is happening with the other kids?

How do, how do they go with that?

They have a lot to, to, to, to learn about

yeah, their brother or sister and things

they don't want to learn because they

also have their, their their own space.

They need their own space.

So there's a lot to learn.

Rupert Isaacson: Do you have the other

family members come for the sessions with

you as well as just the autistic client?

Monique: Yes.

Yes I have.

And then when you have the old

system, so the old family, you can

see what is happening and where the

extensions begins and, and what is

happening, what is happening with

dad, and what is happening with mom.

Mm-hmm.

And what is happening with the little

sister, and why is she afraid, and

why are we going to scream at each

other or what we don't understand?

And the important thing, I think, is

to look at your child with autism.

What is he telling you without words?

Look at him, look at his

eyes, look at his skin.

That are kind of things.

Look at his, his, his fingers.

How is he putting his fingers on?

That, that tells you a lot of information.

You can deal with it.

Rupert Isaacson: I'm intrigued

when you say look at his skin.

Yes.

What do you mean by that?

Monique: When the extension is going too

high, they, they are how do you call it?

Spear ness tension.

The, the muscle extension,

the muscle tension.

You can see it.

There are

Husband: he's making fist.

He is

Monique: making fist.

He is he he is

Husband: looking for pressure.

He's look,

Monique: yeah.

Yeah.

Things like that.

He is, he is.

Sometimes they put also their

hands behind their back to, to, to

look for the how do you call it?

The, the, the, the vegetarian

line, I call it, right?

Rupert Isaacson: The, like the pressure

on the kidneys and the adrenal glands.

Monique: I think, yes, yes.

And to feel where, where am I standing?

Where, where are my feet?

Where are my feet?

Because they need to regular.

And when they are standing to try to

ground on the feets, they are getting

more space in the brain so that can bring

them back into where they really are.

Rupert Isaacson: This is interesting.

You know, I absolutely agree with you.

I, obviously with Horse Boy, we try

to involve as many family members

as we can, partly because for the

reasons that you just outlined, but

also frankly, for selfish reasons.

I will learn more about your child if

the brother and the sister are there,

because I don't know your kid, you know?

No.

And your kid doesn't trust me.

He doesn't know me and the brother and

the sister, they know each other better

even than the parents know the child.

So often, the brother or the sister will

say to me, oh, when he makes that noise,

it means this, or, yes, when, you know,

don't do this, but make sure you do this.

This is really good information

and I, I won't get it unless

I have some expert there.

So I also realize that I need

to make my place attractive

to the brother and the sister.

Maybe they don't like horses,

maybe they like football.

Mm-hmm.

Maybe they like martial arts.

Maybe they do like courses.

So I have to think about

how do I design the session?

We call them play dates, you know?

Yeah.

How do I design the play

date for those children?

And then of course the mother

and the father can relax a little

bit because suddenly they see,

oh, all of my children's needs

are being met in this place.

Yeah.

And then perhaps the brother who

likes football, and I call my friend

who's a professional soccer coach

and say, Hey, I need you on this one.

And suddenly he's getting

amazing soccer coaching.

Yeah.

Because of his brother's autism.

Yeah.

And this changes the dynamic a little

bit, or maybe the sister she's getting

riding lessons on really good horses.

You know, our horses are trained through

the Grand Prix, some of them in dressage.

So we can give her these

incredible experiences because

of her brother's autism.

And it changes the dynamic, you know?

I so agree.

And I, I'm always trying to encourage.

Practitioners to do this, but of course it

can make life more difficult and sometimes

you get parents who are not so helpful.

I know, and I'm sure you know this and

then you have to work with that, but

I, but I find that whether they are

helpful or not, it's still optimal.

Yeah.

If they're all there in terms of the

change that we can affect, it's, you know,

I'm very encouraged to hear you say this.

I'm also interested in what you

said about skin because we noticed

very early with Rowan, with my son.

Mm-hmm.

And then with other children, we

saw there was a pattern that right

before the meltdown, before the

tantrum, before the negative thing,

they would often go very pale.

Yeah.

The color would go pale and you

would see two little dark spots.

Under the eyes.

And eventually we realized

this was lack of protein.

This was a blood sugar crash.

Monique: Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: And that if we could

get a little bit of protein into

them, it was a little bit like putting

gasoline back in the brain drink.

Yeah.

And now we got to the point where we

will always tell the parent or the

caregiver who's bringing the child, make

sure that they, and you have had protein

30 minutes before you come, because

cognitively it will make a difference.

And it was the skin color change.

That first alerted us to this,

and now I see it in everybody.

Yeah.

Including myself.

Like there are sometimes when I'm

like, yeah, and I look at myself

in the mirror, like, oh shit, I

Monique: something, where is it?

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Okay.

So you have a practice, it's called ini.

Yes.

So that's incomp compassion.

Monique: Yes.

Rupert Isaacson: Why this word?

Why compassion?

Monique: Why compassion?

I'll tell you when I started

to on my, on my practice, I,

I didn't have know name yet.

And I have searched and searched

and in Latin and in English and,

and French and, and all kind of

languages came through my mind.

But no, no, no.

It wasn't, it wasn't until,

until, I have to go myself to

the hospital with emergency.

And after three days I became home and I

was lying on the couch and suddenly the

name came up in compassion because it

was time to look at myself in compassion.

It was time.

We have given a lot as, as

parents, and it doesn't mind.

I do it right away, but I don't have

to tell you what it's meant to have

a child with autism, what it costs on

the energy and so, and that was the

moment I thought, yeah, in compassion.

So that's how I became to this name.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

So let's dial back now.

Yeah.

Monique: Speaking

Rupert Isaacson: of the

experience as a parent,

Monique: yes.

Rupert Isaacson: I want both

of you to speak on this now.

Tell me about your journey with Stan.

Let's start at the beginning.

Husband: Okay.

Well, when when Stan was born,

it was how do you say it?

A quick delivery.

When you say quick conflict,

the labor went very fast.

In, in one hour.

Every the sun was there.

Okay.

I mean, and well, we were very happy of

course, because it was our second son

and right away Monique said directly,

there's something special about Sam.

As a parent your child always

is special, but now she said

it in a, in a different way.

There's something special about Stan.

The first two years we didn't notice

anything different, but after a few

years we noticed that he didn't develop

as as the other children, especially

with with spoken words, et cetera.

And there were several times when

there were loud noises or, or other

things or images, something like that.

He put his, he covered his

ears because yeah, he, he, he

couldn't yeah, reflect him.

He didn't know what to do with it.

Then we went to the doctor and the

doctor said we, perhaps he is deaf.

There's something wrong with his ears.

So, we went over there, they didn't

see anything special and but, but he

still covered his ears and yeah, he did,

still didn't develop as the other kids.

So after that we went to another doctor.

He did a lot of tests after that because

they suspect that there was something

wrong in, in they suspect the autism.

They suspected autism.

Yes, yes.

Yeah.

Yeah.

And from there on okay, yeah, of course.

Okay.

First we were very.

Monique: Upset.

Husband: Upset.

Yeah.

Monique: Otherwise, we

already knew something.

It, it wasn't not that strange.

She told us no, because

deep inside we knew

Husband: there's something about someone.

It could be autism.

Yeah.

Yes, it could be autism.

Then we yeah, very quick.

We accepted the, the knowledge

that that son had autism.

So from there on we, we just, yeah.

Put our minds, okay, how can we

help son to, to get along with

his life on a, on a pleasant way.

So, we, we had a, a special case manager,

autism, and she learned us by videos

we made of stem, how stem reacted.

In all kinds of, of circumstances and

especially how we could well predict

when STEM was started to screen.

So we can how do you say that?

Monique: Regulate him.

Husband: Yeah.

Monique: Yeah.

Bye by going

Husband: get him back in

his, his comfort zone.

Yes.

In instead of yeah, sensory processing.

S

Rupert Isaacson: So when you

got him to his comfort zone?

Yeah.

Like bed or so?

Husband: No,

Rupert Isaacson: no, no, no.

What's the comfort zone?

Husband: No, no, no, no.

By getting like an, an

example out the situation.

Yeah.

Out of the situation.

Okay.

Change the situation.

Yeah,

Monique: yeah, yeah.

SPR

Husband: or jump on a

trampoline or, or squeeZ.

Him squeezing him something.

Something to get into the pressure.

Yeah.

Into his body.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Okay.

So change the environment.

Deep pressure active movement.

Yes.

Yes.

Okay.

Outside preferably.

Okay.

Yeah.

This was a good, this was a

good therapist that you found?

Yes.

Unusual.

She

Monique: is very good in her job.

Really?

Yeah.

She, she's very good.

She learns.

She, she has learned us a

Rupert Isaacson: lot.

Do, do you still work with this person?

Monique: No.

No.

She after I think about, she

became here three years, I think.

Three years, yeah.

After three years.

And then she really told us.

You are so good as parents,

you don't need me anymore.

Yeah, you can, you can do it your own.

And when she was walking through that

door, you have something No, don't go.

I need you.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

But then

Monique: you are going to do it

on your own and you are, and,

and it's became very well because

Rupert Isaacson: How old was he

during this process this time?

Monique: It was about four years.

He was about four years.

Yeah.

He was, he was a little, a little one.

Really?

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

So, so she shows you, the therapist,

shows you some good techniques for Yes.

Yeah.

Sensory processing for changing

the environment, for Yes.

Giving deep pressure, et cetera, movement.

Yes.

What happens next?

What,

Monique: What happens next?

Well,

Husband: when he was

eight, eight years old.

We heard about yeah, very good results of

children who had dolphin therapy in Uraba.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Husband: Yeah.

And we knew the man who was well, the

arranged everything, yeah, arranged

Rupert Isaacson: that, that

kind of journeys to kids.

How did you know this man out of interest?

Monique: He his how do you call it?

His, his

Husband: He went to kindergarten

and there was a teacher.

Okay.

Oh, yes.

You told us about that.

That Ah, yeah.

Yeah.

And so we made contact and then you,

there was they put you on a list.

You had.

It's, it's a, it's a foundation where

you have to do all, all kinds of things

to raise money so you can get with yeah.

With your family.

With your family to dolphin therapy.

And

Rupert Isaacson: they, okay.

Husband: They pay you the,

the, the ticket, eh, to, to fly

over there and and the therapy.

They, they, is

Rupert Isaacson: this, I'm

just looking online now.

Is this the URA Dolphin

Therapy and Research Center?

Yeah.

Husband: Yes, that's it.

Say it c say

Rupert Isaacson: it.

CDTC.

CDTC.

Yeah.

I've pulled it up on my Google.

It looks really interesting.

Okay.

You raise the money, you go.

Monique: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

And what happens?

Monique: What happens?

Well, the first time we went over there,

Stan was screaming in front of the plane.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Monique: Well, my my teeth are rolling.

And but we went over there and it was,

it was amazing what happens over there

because Stan couldn't still talk.

We don't have any, the logic with him,

he, we, we couldn't, we, we didn't know

how it, how it, how, how he was feeling

when, when he was sad or happy or nothing.

Right.

So, over there you have to go

two weeks you are over there.

Yeah.

And you are swimming with the

dolphins five times a week.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

And,

Monique: Also the other kids, they

get a special program to put them

also in the lights because Yeah,

they have to do a lot things.

They don't want to because they

have a brother with autism.

So then it is also

especially for them yeah.

And for us it was also an eyeopener

because you see a lot things happen.

You, you don't have the time

before that because you are always

busy to, to have your family

good and, and get it well done.

Everything.

And, and so over there Stan goes to

the ducks and they are squeeze them.

They, they had a lot of send your

Husband: regulation.

Regulation.

Yeah.

Monique: And then they are

going to, practice with him with

letters from the alphabet and they

recognize he was very good while

Rupert Isaacson: he's with the dolphin.

Yes.

Or after he's been with the dolphin?

No, he was

Monique: with the dolphin.

It was on and off.

He was a little time on the dock.

Then they are doing a

practice with him On the

Rupert Isaacson: dock.

Monique: On the dock, yes.

And then it, it was about

a minute or 10, I think.

And then he gave to

swim with the dolphins.

Yeah.

And then he swim for 10 minutes and

then they are doing a practice again.

And that was for an hour.

Rupert Isaacson: So they'd, he'd

swim with the dolphin, then they'd

go onto the dock, work on letters,

work on How would they work on

letters when they were on the dock?

Monique: Ah,

Husband: What they, what they did

was they showed some a letter.

Mm.

They, they pronounced it,

how, how do you call that?

Letter?

And every time when Stu said it

right, the, the dolphin did a trick.

Oh.

So they, they stimulated Stu

to, to say the right word they,

and to pronounce it right.

And he get he got a reward

by a trick from the dolphin.

From Dolphin, dolphin.

The

Rupert Isaacson: reward was

the dolphin did something cool.

Yes, yes.

This is really interesting.

Always.

Husband: It almost looked

like like, like, like Pavlov.

If, if you a lot, eh,

Rupert Isaacson: yeah.

But that's my kind of Pavlov.

If you're going to, if you're

gonna do that with me, then yeah.

Have a dolphin do something.

Cool.

I will probably be motivated.

Yeah.

I mean, yeah.

I've got, can I ask a couple

of practical questions?

I'm, I'm.

I'm really intrigued.

So something which I've seen can

be tricky when you are working with

children in the ocean or in water.

Mm-hmm.

Is the sensory issue of putting

on a wetsuit or putting on a

flirtation device or something.

Mm-hmm.

We used to do autism

surf camps in California.

Mm-hmm.

We probably would do it again.

We just got busy with other things and

some kids there was no problem at all.

Other kids, you really, of course,

had to work for some time on

just the wetsuit or something.

So were there any issues like this with

Stan or with other kids that you saw?

And then of course after that

there's the water and then

there's the big animal itself.

So can you just talk to me?

Yeah.

The sensory issues of.

Whatever equipment he had to have

on his body, the sensory issues

of the water, and then the sensory

slash fear of this big dolphin.

Like what was, what was,

how did it progress for him?

Monique: Well, the wetsuit there was a

little thing because it is, yeah, from,

from his, his angle till his shoulder.

It was and but he, he, yeah.

When he knew I'm going into the

water, it seems like it was okay

because I think that's our lock

stand is very good in the water.

Okay.

He's a very good swimmer.

Yeah.

And he's not afraid of dos.

He likes it.

He get a special yeah.

Vest arm I don't know how

you call it, pressure vest.

The pressure vest that keeps him

above the water because otherwise

he had Oh, a flotation Yeah.

Device.

Yeah,

Rupert Isaacson: yeah,

Monique: yeah, yeah.

But our son, he would, every time

he would like to die with the

dolphins, when the dolphins, yeah.

Going to die, he thought

okay, I'm going with you.

But it couldn't because

he had that crazy, so,

Rupert Isaacson: and this,

how did he react to that?

Monique: It, it it goes very well, but he

was the lucky man because after a day or

10 by getting therapy, his therapist told

us he may go diving with the dolphins.

Rupert Isaacson: Wow.

Okay.

Yeah.

So the,

Monique: the thing we said it is

okay, but please dive with him because

he doesn't know anything about.

How deep the dolphin is going or, yeah.

So please, and go with him.

And they have done that,

and it was beautiful.

He was, yeah, he was, he was, yeah.

Ecstatic.

It was, it was beautiful.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: How long did the

sessions with the dolphin last?

About an hour.

Husband: Yeah.

The, the, the whole session was two hours.

Was two hours, yeah.

The first hour they were on the docks

and doing therapy like, like squeezing

and, and he had to make puzzles

at et cetera that kind of stuff.

He didn't like that at the

first at the first three or four

times he was screaming a lot.

But after that he, he well, he

recognized that if he did the, the.

The, the playing and the therapy.

Right.

Is reward again, was swimming with the

dolphins and that he, he, he liked a lot.

And the total session was, was two

hours, five days a week at the same time.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Now you told me when we were

speaking before I hit record you

told me that he became really verbal

during his time with the Dolphins.

Can you describe the before,

during, and after of that process?

Husband: Well, I mentioned already

he, when when things were difficult

for Sam, for Sam to understand because

it, it, it was well, it, it, yeah,

just, it was too difficult for him.

He, he didn't understand what,

what they wanted from him or

what to do or what to see.

Something like that.

He can, could only express his, his,

his feelings by screaming because

he, he didn't talk at all after.

And, and, and my Monique just

mentioned how we went to, into

the plane with a lot of screaming.

And when we went back, he didn't scream

at all because the most important

thing we've learned over there is when

we predict what's going to happen.

For some it, it, it is, it

gives him a lot of rest.

He feels comfortable, comfortable

about knowing what is going to happen.

That's one of the things we've,

we've learned over there.

We also have learned to, to look at

some and go with his with his tempo,

with his way, his rhythm of living.

Yeah.

That, that are the most important

things we, we've learned.

Yes.

Over there.

Monique: Yes.

And, and the, the thing about the, the,

the words he, he, he was learning the,

the, the letters, the words, the we are

people who like to talk and we talk a lot,

but because we think we can, everything

arrange with talking, talking, talking.

But silence is saying much more.

And that was also with Stan when

when we went over there and they saw

he was doing it very well with his

letters and, and that kind of thing.

And we came home school picked it up also.

His teacher said, okay,

that's very nice to hear.

We are going further with that.

We taken that, that kind of therapy.

Further with him so he can learn words

and we call it in Dutch word build.

And so he had word,

Rupert Isaacson: image.

Word?

Word image.

Word picture.

Yeah.

Monique: And, and because he, he

visual, he's, he's very strong.

And that was his way to learn

words and learn the meaning of

the words, because that was also

what makes him uncomfortable.

Because when we are talking,

there are a lot of words.

He doesn't say anything to him.

He, he understand, what

are you talking about?

I hear a lot of noise, but I

don't know what you are telling

me or what are you talking about?

So that, that makes extension a lot,

a lot of more and, and, and, yeah.

So he became to screaming,

et cetera, et cetera.

And when school, yeah.

Take it over from there.

Yeah.

They, they, he makes, he makes, yeah.

Husband: The screaming.

Yeah.

Went away.

Went

Monique: when, after a few, yeah.

Yeah.

It

Husband: stopped.

Totally.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: And he, when he came back

from the Dolphins, he was able to talk,

he was able to express his needs and say,

Hungry Mommy, I'm thirsty.

Or was it still in the early stages?

Monique: No, he still doesn't do that.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Monique: He still doesn't do that.

It's never when he came back at home

then he will go for his drink and

his candy, but he will never tell

us from himself what he has done.

Never.

We always have to ask

Rupert Isaacson: him.

Okay.

Monique: Yeah.

He will never.

Rupert Isaacson: When, can you

describe how he is verbal now?

Like how you, how he would talk to you?

Monique: Well, we recognize that his

meaning is, is a lot bigger of words.

So he can in that way

explain what, what you want.

That is, that is going very well.

And that's his progress he made.

Rupert Isaacson: Can

you give me an example?

Husband: Well,

Monique: yeah.

Husband: First of all in the beginning

when we asked him how was school,

it was good and nothing more.

Rupert Isaacson: That

sounds like many kids.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Husband: It was like, I know.

But when you asked what have

you, what what have you done on

school have you done at school?

He didn't say anything, but now he

he tells us in in, in a few words,

i, I have I have swing, I have

puzzled, I have been with the animals.

So yeah, that kind of of words.

He used to tell us what he

what his day was, what his

day was what his day like was.

Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: And okay.

So you, when he came back from

URA South the first time, 'cause

I know you went two times.

Yes.

What would you say, how was he

speaking after that first trip?

How was he using words?

Monique: Very functional.

Yeah.

Stan is a boy who was very functional.

So he get his, his things he needs

Husband: by drinking,

by, yes, by food, by,

Rupert Isaacson: playing.

So would he say, would he ask for

things or how was he expressing himself?

Yes.

Monique: Well, that

became so about the years.

He, he he's going to

to do that a lot more.

When he don't want anything or he don't

want to tell us anything more, then he,

he, he said to ans to us, no, not anymore.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Monique: So that's, that's

something he has learned.

When I don't want anything

anymore, I have to tell them.

Rupert Isaacson: And

this began after Carissa?

Yes.

Monique: And yes.

Yes, yes, yes.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

This is really interesting.

I often when I'm giving people

trainings, I tell them, you must

value negative communication as

highly as positive communication.

Yeah.

Because when you're dealing with somebody

who's nonverbal, if they tell you what

they don't like and what they don't

want, this is massive progress, you know?

Yeah.

Please tell me what else

you don't want to do.

And of course, in normal parenting,

this is regarded as you know, a real

problem when the kids are negative and

they, but of course, from our point

of view, often things happen that way.

First.

No, I don't want, and I suppose in a way

it is the same with neurotypical IE normal

kids, they usually actually start with no.

Yeah.

At two years old, you know, now and then

from, that's the first self-advocacy.

So you saw that after Issa the first time?

Yes.

Yes.

You went back again, how long between the

two, was it the next year, three years?

Three years.

Three years?

Why, why three years?

And tell me what happened

on the second trip.

Monique: Well, he did it very

good at school and you have

also the time to make that, that

money you needed to go out there.

Okay.

So, you are when you went out there,

you going beneath or do you call it?

At last on the, on the,

on the, on the list?

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Okay.

You

Monique: start all over again to

Rupert Isaacson: get on top.

To

Monique: get on top,

Rupert Isaacson: yeah.

Oh, I see.

There's a list.

Monique: Yes, yes, yes.

There's a list.

And so you have to do things to, to

get your money again, to go over there.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Monique: So, that's why.

And then when when it is already

there and you can go to Cura South,

then also has to be there some place

to go.

So, that's why the three years.

Got it.

Yes.

Yes.

Rupert Isaacson: If you're in the

equine assisted field, or if you're

considering a career in the equine

assisted field, you might want to consider

taking one of our three neuroscience

backed equine assisted programs.

Horseboy method, now established

for 20 years, is the original

Equine assisted program specifically

designed for autism, mentored by and

developed in conjunction with Dr.

Temple Grandin and many

other neuroscientists.

We work in the saddle

with younger children.

Helping them create oxytocin in their

bodies and neuroplasticity in the brain.

It works incredibly well.

It's now in about 40 countries.

Check it out.

If you're working without horses,

you might want to look at movement

method, which gets a very, very

similar effect, but can also be

applied in schools, in homes.

If you're working with families, you can

give them really tangible exercises to do

at home that will create neuroplasticity.

when they're not with you.

Finally, we have taquine

equine integration.

If you know anything about our

programs, you know that we need a

really high standard of horsemanship

in order to create the oxytocin

in the body of the person that

we're working with, child or adult.

So, this means we need to train

a horse in collection, but this

also has a really beneficial

effect on the horse's well being.

And it also ends your time conflict,

where you're wondering, oh my gosh, how

am I going to condition my horses and

maintain them and give them what they

need, as well as Serving my clients.

Takine equine integration aimed

at a more adult client base

absolutely gives you this.

Okay.

So tell me what happened

on that second trip.

Monique: Well, we had still a

little thing because Stan still

wearing diapers at that age.

At that age

Rupert Isaacson: he would be by then 12.

Yeah, 11.

Yeah, 11.

Monique: Yeah.

Yeah.

So that was our next thing.

We, that

Husband: that was our main goal.

Monique: Goal, yeah.

Yeah.

And well, it, it also went

very well, not directly.

Because when we went over there, they

have done a lot of other things instead

of wearing the di the, the diaper

and, and doing something about that.

It's actually almost the same

when I am working with my horses.

It's, it's in the moment what, what,

what tells the horse what to do.

So, and it was also with the dolphins.

So the second time yeah.

What, what had they do?

They, they, they make him,

Husband: especially, they learn how Yeah.

To, to wait.

Yeah.

And to get the patience about

things he want or or otherwise

things we have to do first.

Before we can help or we can do things

with some That's the, the, the, yeah.

Most important thing.

They have learned him to wait and they

also have, have learned us to because

we always had the focus on some,

but we also have two other children

and they also need our attention.

But when we were doing something

with the other children and we saw

that Stu was asking for us, or, or

he was was was high in his yeah.

In extension.

Yeah, in extension.

Then we sort automatically went to Stu to

help him, and they say that's not, well,

not quite fair to the other children.

So we have learned to say Tostan, no stem.

Monique: Not now what?

Husband: Not now.

You have to wait for a moment,

but after this we come to you.

Yeah.

And that also went with as, as Stum

asked for, can I get some candy?

We said and it also was almost

dinner time, something like that.

Then we said to stone, no stone,

you can't have candy, but you can

get a banana or something like

that, something else instead.

So we learned to, to bend things

that weren't quite right for

stone into group things and Yeah.

Monique: Yeah.

And patience.

And patience.

Yeah.

And he learned quite well.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

So, but did the toilet training with the

diapers advance during the second trip?

Monique: No.

Well, no.

That's not quite right.

It became better when we went home.

And after that he only had it by nights.

Yeah.

Okay.

He was wearing a diaper,

so that went very well.

And I think about when he was, I think 13.

Yeah, something like that.

He didn't wear it at all.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Tell me, finish

Monique: with it.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Monique: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: I'm, I'm interested

to know what did they do in Issa

to target the toilet training, but

Monique: actually nothing because

they have other targets with him.

Rupert Isaacson: So why do

you think it changed to only

nights after that second trip?

Monique: Well, we think that because he

became to learn better how, how his, how

his body was working and how his tension.

He could regular it on better

ways he gets space in his mind.

And so he get also a signal

I have to go to the bathroom.

Yeah.

And that was and that, that was

also what we have learned from, from

Charles with, with with autism that

they don't get a single right away.

And and that was with, with Stan, he

he get a sign, I, I have to sign on

the, on the single, and I, I, I have,

I have to go to the bathroom and yeah.

From, from from, yeah.

The, the, yeah.

Well,

Husband: the, the most important

lesson we've learned, and that's

with a lot of things with Stu.

Stu does things when he is ready, ready

Monique: for it.

Yeah.

Husband: You can't push things.

To, to get it, to get it done.

Because if he isn't ready in his mind

and in his body you don't get resolved.

So you have to recognize when he's

ready to, to learn something, to

accept something, to do something,

Rupert Isaacson: you know,

listening to the story.

I can also imagine some things

happening in his brain during this time

with the dolphins because you going

somewhere very new, very different.

I very be surprising in a good way.

Yeah.

Magical, you know, this time with

dolphins and of course what happens

and a lot of movement involved and

a lot of natural sensory stuff.

You're in water, you're with the

big animal, you are, you've got the,

sensory, comfort of the deep pressure

of the person in the water with you.

All of these things.

And with this comes a

neurological reaction.

Yeah, accelerated, which we would

call neuroplasticity, but specifically

the production of a protein in

the brain, which happens whenever

you do something new basically.

Particularly if it's physical moving

and problem solving effectively.

And that's a protein with a, its

name is four letters, BDNF, brain

derived neurotrophic factor.

When you do something with what

one calls novel movement, let's

say you sit on a horse, let's

say you're going in the water.

Let's say you run across.

A field.

Yeah.

It's very different running across

a field to running on a playground

because on the playground you

don't need to think too much.

Where do my feet go?

On the field, you must think

because if you put your foot in the

wrong place, you fall over because

there's a little hole or something.

So your mind has to be more active.

You go with the dolphin,

you go with the horse.

This effect is amplified.

And so you get incredible amounts of

neuroplasticity, of brain development

in these types of situation.

And then of course, this could

be very scary, which would shut

down the brain development.

But of course he's there with the family.

He's there with all this love.

He's there.

There's I'm sure all kinds of.

Heart resonance coming from the

dolphin, which has a very big heart

throwing off an electromagnetic field.

Yeah.

Yes, indeed.

It's very big.

And of course the dolphin being this

hyper intelligent com, you know,

social compassionate animal is doing

all kinds of work with him on a level

that we can't even probably see.

You put all this together, I can

see how he could come back from

that experience, able to regulate

his toileting, for example, because

of the, the brain development.

Okay, so we've talked about dolphins

and this is wonderful, and actually I'm

going to have these guys on the show.

I'm going to reach out to them, even

though it's not equine, it's still,

you know, large animals and nature.

Yeah.

We need to talk to these people.

Clearly they will have things that we can

learn from, but let's go to horses now.

So, Monique, you are a horse woman?

Yes.

Were you always a horse woman?

Yes.

Monique: Grew up with

Rupert Isaacson: it.

I'm nearly

Monique: born in the unstable.

Okay, okay.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: So since

you were a kid, horses.

Horses, right?

Yes.

And were you having horses,

owning horses while Stan was in

his early years of development?

Yes.

And what was Stan's involvement

or interaction with these horses?

Monique: Yes.

We've always had horses and when we get

this, this house where we are living now

I have my horses standing by our house.

They were first standing with my

parents, but then they moved to us.

Okay.

And yeah.

Stu and animals are just one.

That's okay.

If it is a prock a dog,

a cat, a horse, never.

Mines where animals are there

is stem and with a horse.

We had a pony called Oscar,

and Oscar is a lovely horse.

And what he did, he had a very

big buckets and he put it behind

the top there, you call it.

Yeah.

And he was standing on.

And he was for an hour busy with a

horse to go on the back of the horse.

Rupert Isaacson: So he used

the bucket to climb on top?

Monique: Yes, yes.

But the horse fought then.

Oh no.

Oh no.

Ride it there.

That's, that's, that's better food.

So I'm going to walk over there.

And Stan was then taking the

bucket with him, put it on

the ground again, stand on it.

And so he was for an hour

busy with this horse.

It was lovely to see.

And when he sat on his

back, he was enjoying it.

He was just sitting there, just look

over what, what, what kind of birds

was were, were, were flying in the air.

What he saw, what he was feeling

like what, and he Yeah, he was, he

was really zen when he was with the

Rupert Isaacson: horse.

And how long this, and, sorry.

Okay.

At this point, you are

not running in capacity.

You don't have a practice?

No.

No.

What do you do you doing for a living?

Are you just busy being a mom because you

have three kids and a special needs kid?

Are you Yes.

Trying to do a job.

Monique: Yes.

I had a job.

I had a job.

But when we knew it was a very

busy Trix, we call it, I think.

Yeah.

Therapy with our family, yeah.

It was very stressful.

Also for us.

My husband just became his own office

and our daughter was very little.

And I thought, no, no.

Working by job elsewhere, it's, it's not

gonna bring us that, that we need it.

Yeah.

So, I stopped my job.

I was working also on the

office and I was full-time mom.

I liked it, but most of all,

I think our family became in,

in another, another dimension.

We, we get spaces.

We, we, yeah, there was, there

was, yeah, we, we, it was

Rupert Isaacson: time.

Yeah, time.

Yeah.

Yeah.

We

Monique: get another energy in our house.

So, and that was very, very nice.

And I did some other college because I

don't want to sit, just sit being a mom.

I also want to develop so,

I did how do you call it?

Yeah.

Yeah, I did some developing college

skills, champion, develop and, and,

so, and then I thought, yeah, yeah,

but I have horses and I have the

experience of our son, and when I

put it in a big bucket and I'm going

to do something about that, maybe

something beautiful is going to happen.

And so, my practice in Compe came

and I thought there is when I see my

own experience, what my bosses bring

me in times that weren't that nice.

I thought, yeah, yeah, I would

like to give other ones also this.

I, I, I think, I really think with all

the experience I have, we have, we can

learn other parents how you can deal

with a child like Stu who has autism.

There is.

Such a lot to learn in our for

example, temple Grandin, you know,

where it was, it was our inspiration.

And I've put it also in, in our blog

from Ura Sao, what she brings us.

And always she is, she is coming

in my mind when I, when I have it

a little bit difficult for myself,

then I think of Temple Grandin.

When you are throwing the other

door open, then go for it because

there are other things you can see.

And, and yeah, it brings us a lot.

And also in my practice with the horses,

because that's the other door, the,

the, the horses they are just there.

And when you are in the neighborhoods

of horses, it'll just started.

It starts to brings you yeah.

Such, such more, I don't, I don't know.

I, how can I, yeah.

I always, yeah,

Rupert Isaacson: sure.

I mean, you're preaching to the

converted here because we all

Monique: Yeah, yeah.

Everyone

Rupert Isaacson: listening

to this show, we, we know the

value of the horse in Yeah.

Various ways.

And what they bring a question though.

How old was Stan when you started

your income capacity practice?

Monique: Well, I have now my

practice for only three years.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Yeah.

So you had to develop

a lot of time for him.

Yes.

So by the time he was sort

of in his late teens Yeah.

Yes.

You, to turn your attention Yes.

To saying, how do I help other families?

Yes.

Got it.

Okay.

So I'd like to talk a little bit

about how you run your practice,

but before that, everyone will

want to know how is Stan doing now?

Where is he at?

You know, and, and just for,

the listeners and viewers,

Stan does not just have autism.

He also does have an inter a

diagnosed intellectual disability

in parallel with the autism.

Yeah.

So, one's expectations and so on must

be to some degree directed by this,

but just so that people understand the

this neurological geography of, of Yes.

So, so, so tell us, you

know, where is Stan now?

What's his life?

What's his day?

What's, yeah.

And then let's get to encompassing.

Monique: Yes.

Well, he is going for now for five days

a week to how do you, how do we call that

earlier special daycare, special daycare.

Yeah, something like that.

Their

Rupert Isaacson: services sort of thing.

Yeah,

Monique: yeah, yeah.

Where he can also go to animals.

Yeah.

And he is a very he's in a, in a

very active group with the other

Husband: yeah, they're working a lot.

Yeah.

Monique: They're,

Husband: they're, they're swinging.

They're, they're, they, they're

constantly busy with him.

You

Rupert Isaacson: told

before in a certain way.

He's in, they're in nature a lot.

What do they do in nature?

Monique: Yes, they are going

riding with car and horses.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

So he's 49

Monique: and then they go into the forest.

Yeah.

He likes that a lot.

He also goes to they have a donkey.

They have chicken they have

Rupert Isaacson: at the daycare.

Is it like a castle?

Is it what you would call a care farm?

Monique: Kind of that, kind

of that, but they also have

a lot of sports they can do.

Okay.

All they light.

Yeah.

So, there are, who goes to the gym?

There are they, they going swimming?

They are, they go for a long walk.

Some they are going to, to do

some shopping in the village.

They also, so they have to go for a walk.

And when he is busy with his buddy.

Buddy, yeah.

Yeah.

Then, then his mind's getting, getting

the opportunity to, to learn to develop.

So that's very beautiful to see.

And

Rupert Isaacson: what is he learning?

Monique: Well, we are we are recognized

that, that he is giving much more meaning

to words and he can explain things better.

And he is happier on his way.

It, it, it doesn't.

Custom.

Yeah.

Husband: And he takes initiative

to, to tell something.

Yeah.

What, what has happened that day?

What he has seen.

He wants to tell us things.

Yeah.

He wants to tell us.

Yeah.

But he

Monique: also we had a couple

of weeks ago it was a holiday

and we should went to the sea.

To the beach.

Yeah.

To the beach.

Yeah.

And the big beach he call it.

And so I told him, okay,

and, and what do we need?

And he begin to talk.

I, I thought, no, no, you can write.

I told him, here, take a pen.

Take a pencil and a paper

and put it on the paper.

And so he did.

And so he began to write it down

what we had to need for that day.

Mm-hmm.

Husband: Yeah.

Wow.

Wonderful.

He made a, he made a list of about

six or seven things he, he went

to get with him to the beach.

Yes.

But

Monique: in a way that he was also happy.

It wasn't, it, it, he was happy to do it.

And that's what we recognize

what he is doing now.

It doesn't, it doesn't take

that much energy of him.

He likes to do it because he can, and

a couple of years ago it, he can't.

Yeah, because, because he couldn't do it.

No, because he, he did, he,

Husband: it always looked like he was

under pressure to do, to do it something.

Rupert Isaacson: Right, right.

Not spontaneous.

Yeah.

Quite understand.

Husband: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Yes.

Wonderful.

Okay.

And he's still obviously

involved in animals in nature.

And then when he's at home with you,

while there's horses around, there's Yes.

Yes.

We have

Monique: two dogs.

We have two cats.

Yeah.

So he's always always into dogs.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Tell me about

his interaction with the dogs.

Monique: Well, he has one particularly

that's it's, it's a Labrador

and that's really his buddy.

Yeah.

When he's coming home he is taking

some time after the computer.

Then we are going for a eat, and then

he is going to take the dog for a walk.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Monique: And also with the horses

when they are going somewhere,

they are one, they are really

one where the darkest is Stu.

And where Stu is, is the dark and

everyone in the neighborhood knows it.

And yeah, he's doing very well with it.

Husband: Completely on his own.

On his own for about an

hour or an hour and a half.

He's, he's gone with the dogs

in, in nature and then Yes.

And he

Monique: has he gets a GPS on it

Rupert Isaacson: so we know

Monique: Yeah.

A tracker.

So we know where he is.

Rupert Isaacson: And also the dog

always knows the way home, presumably.

Yes,

Monique: yes.

Yeah, yeah.

With ice closed.

Rupert Isaacson: Yes.

Monique: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: I remember when

with my son Ron, when he was first

coming to visit us in Germany.

He loves to be given challenges,

so I would give him challenge.

Okay.

I I'm gonna drop you there in the car.

On the top of that mountain with the dog,

and you are gonna find your way home.

You can GPS it, but the

dog is gonna say it.

None of it.

Yeah.

You, you, you can just, yeah.

Yeah.

Wonderful.

Yeah.

And it really worked.

It, it's, it's very beautiful to see how

each type of animal really does bring

out a different aspect of the human.

And it's, it's something which

I'm often encouraging our equine

practitioners to think beyond the horse.

You know, horses, they're fantastic.

They do all these amazing things, but

don't limit yourself because what if this

person is not so motivated by the horse?

Or maybe they were motivated by the

horse, but for some reason now they

lose that enthusiasm a little bit.

My own son, for example, he's

gone in and out of horses.

Over his life, and sometimes he's really

into the horse and sometimes, ah, it's

not so much, and I must go with this.

Monique: Yeah.

Mm-hmm.

Yeah, I need

Rupert Isaacson: more than that.

Monique: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: So as you know, we

work with all kinds of animals and

nature but sometimes horse people can

be a little bit autistic themselves

and it's just very horse, you know.

I am similar, you know, if you leave

me to myself, I'm just horse, horse,

horse, horse, horse, horse, horse.

But I, I realize that

there are some limitations.

No thanks.

if you're a horse nerd, and if you're on

this podcast, I'm guessing you are, then

you've probably also always wondered a

little bit about the old master system.

of dressage training.

If you go and check out our Helios Harmony

program, we outline there step by step

exactly how to train your horse from

the ground to become the dressage horse

of your dreams in a way that absolutely

serves the physical, mental and emotional

well being of the horse and the rider.

Intrigued?

Like to know more?

Go to our website, Helios Harmony.

Check out the free introduction course.

Take it from there.

Okay, so Stan is doing really well,

and now you are in a, in a position to

give your experience to other families.

Talk us through okay.

Let's say I am an autism

dad and I find my way to.

Your website.

Monique: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: I make contact with you.

I'm new.

Monique: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Tell me how it will go.

Monique: Yeah.

Well, first of all, I'm going to invite

you of course, and the first thing I, I

do when I get someone here who is Alre,

where I already knew he is autistic I

look at his body, what is he telling me?

And that's very important because

we have talked it earlier.

The body is telling me everything.

And I quite often see that when I

have a session with a mom or dad

or who are also autistic or the kid

they are going to look for something.

Diarying the sissy to regulate themselves.

So it's about a bracelet

a earing their hair.

They find stuff.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah, we all stem

Monique: Yes, all of us

Rupert Isaacson: to Yes.

Regulate ourselves.

Yes, yes.

Monique: Especially when it's

going to be difficult, then Yeah.

Then oh, oh, oh my gosh,

I have so regulate because

this, this is very difficult.

This.

Yeah.

And that's what triggers me.

And when I throw it back at

them then I get the answers.

Yeah.

It is difficult.

Yeah.

Emotions are difficult for me.

Yeah.

This is a big part for of me.

So.

That's my comm communication.

And are you always

Rupert Isaacson: asking the

whole family to come, or as

many family members as possible?

Or do you start with just the

kid, or how do you, how do you go?

Monique: Yeah.

Just what they want, because I

always have the respect of them.

What is what you need and

what is it, what you want?

I want to give a lot.

Mm-hmm.

But it also, it I want to know what

do you want and what do you need

and how does it go all the way?

So, sometimes I began with the parents.

They said, said also, well, first us fine.

Fine.

Okay.

So sometimes

Rupert Isaacson: you'll do your first

consultation with just the parents.

Yes.

And sometimes I know that's a good idea.

Monique: Yeah.

Yeah.

And sometimes they told

me well, here we are.

And then therefore they old family.

Okay.

Also good.

So it's really yeah, I, I, I feel it.

Like, what is my intuition

tells me what to do.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

So how do your horses enter the picture?

Monique: What do you mean by that?

Rupert Isaacson: How do you, okay, now the

parents have come or the family has come.

You're observing their bodies.

You're, you are finding out what they

need to regulate themselves and so on.

Now you're going to add a horse.

Monique: Yes.

Yes.

How,

Rupert Isaacson: how does this happen?

Monique: Yes.

I'm going to look for the horses.

What he's telling me, is

he standing by the stomach?

Is he breathing out?

Is he walking the horse?

Yes, the horse, that kind of thing.

Rupert Isaacson: So is the horse coming

into a space with the person now?

Yes.

Okay.

Yes,

Monique: yes, yes.

And, I also, when the knees are

there I have also a little boy who

I have put on the pony because he

came from the hospital and he was

sent from a specialist over there.

He had some problem to go to

the bathroom just like our son.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Monique: And that mother calls me

and tells me that, oh, and he can't

go to the, and he has medicine and

I don't want that medicine anymore.

I want to go in for himself

to go to the bathroom.

Can you please help me?

Of course.

Come over here and we gonna have a look.

And that boy became two times

here and he go to the bathroom.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Riding on the back,

Monique: riding on the deck of the

horse and he go to the bathroom.

He

Rupert Isaacson: took a poo on the horse.

Monique: Yeah.

Yeah.

Wonderful.

Wonderful.

And that's exactly what we are doing.

And that's also what you are doing

with the kids who on the horse

and your story with, with Rowan.

So I had to think about you

when it, when it happens.

I thought, yeah, this, this kind of story.

And now I have it myself, my own.

So the mother is very glad

about that, but now, okay.

The new school year has became and,

and become, and, and she's calling

me again because the kid has a lot of

tension and new again, he doesn't go

to the toilet, so we have to go again.

It's, it is, yeah.

I don't mind 'cause I know it's

gonna be all right and I know where

it's from that get a lot of tension.

So it will be, be going all

right after a few times.

Rupert Isaacson: So you do

work with people riding as

well as people on the ground?

Yes.

Yes.

How do you decide

how to proceed?

Monique: What the question of the parents

is I only put children on the podium.

Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: Not parents.

Okay.

Monique: No, the parents are

always standing besides the horse.

Mm-hmm.

Yes.

So the children, I put them on the

horses and I also learned them.

Other things, also school things.

We have special therapy we call

it different learning by horses.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

And

Monique: that's for child.

The who, who doesn't come

Husband: come along with, come

along with, yeah, with, with

words and, and mathematics.

Yeah.

Something like that.

Rupert Isaacson: And is that something

you've developed yourself or is that No.

No.

So that program that you use,

that's an outside program?

Monique: Yes, yes.

I've learned that

Rupert Isaacson: learning

with horses, it's called,

Monique: Yes, it's, yes.

Rupert Isaacson: And is that a,

a, a Dutch thing or is that a yes?

Yeah.

Okay.

So tell me how that works.

Monique: Yes, it is.

Well, finally, you are going back

in time how we learned on school.

Mm-hmm.

That's the part they, they don't give

it on that way anymore on school.

So, what

Rupert Isaacson: do you mean?

Monique: What do I mean?

Rupert Isaacson: Learning

through repetition.

Yeah, yeah, yeah,

Monique: yeah, yeah.

Yeah.

And it is, it is the same as

the mother with, with her boy

who doesn't go to the toilet.

Mm-hmm.

Now the horse is the

biggest friend of that child

Rupert Isaacson: who,

Monique: who, who counts read or, or

writes or, or something like that.

And when the horse is

with him, it goes on.

It goes because the, the tension

is gone and there's another, so

Rupert Isaacson: when, when you

are working with the academic stuff

on the horses, the learning with

horses, are you using the horse's

movement as a rhythm to then create

repe repetition of saying things and

giving information into the brain?

Yes.

Sometimes.

Is it working like that?

Monique: Sometimes.

And we also do some, some

how do you call it, to bags?

Yeah.

Bags.

Bags right.

And, and left mm-hmm.

On the child when they are on the horses.

Mm-hmm.

And then we tell them to take something

out of the left, back with the right hand.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Okay.

Also crossing the midline,

you want them to Yes.

Yes.

That's also for the BDNF

in the brain, right?

Monique: Exactly.

Exactly.

Rupert Isaacson: But when you are

dealing with an academic concept, like

say numbers and you are doing this

on the horse, tell me how it works.

How, how are you doing it?

Monique: We have a couple

of things, how we do it.

Sometimes first we do it when

they take the horse beside them.

So they walk with the horse.

Yeah.

And then just simply from one till

10 or we put how do you call it?

Yeah, many of further mm-hmm.

But, but yeah.

Let's keep it easy.

My English is not that good.

How can I explain it?

The,

Husband: the practice from the

numbers from 0, 10, 20, 30, 45.

Rupert Isaacson: Counting.

Yes.

Yes.

Counting.

Yeah.

Okay.

So you could count steps.

You could count, yes.

Yes.

But okay.

But let's say you want to do arithmetic.

Let's say you want to do division.

How would you do that?

Monique: What do you mean exactly?

Rupert Isaacson: Well, for example, when

I was teaching my son numbers and letters

on the horse, initially what happened was

I would, I followed his interests, right?

So he loved the Lion King.

Mm-hmm.

So I would be singing the Lion King songs.

Don't worry, I'm not going to sing now.

And then I would take the

ca a character like say.

Zu and I would put the letters

of Zazu on these different trees.

Yes, we would ride, but you

know, at least 30 seconds of

riding in between each letter.

Mm-hmm.

So the trees are at a distance.

We can also learn what

is this tree, et cetera.

And then at the end there'd be a

little toy of azi and he learned

to put the letters together.

And then from there, very

quickly it went out to reading.

Similarly with numbers I would

start with counting, counting

the steps of the horse and so on.

And then counting things from the horse.

Yeah.

But then I could get friends and

family members to stand together.

One of them wears a silly

hat that one has to go.

So push that one away, making farts.

Because it's funny.

And then we see how many are left

and then this person starts to

cry because they're by themselves.

So we have to put them back.

And how many have we got?

And then say that's

adding and subtracting.

But then with division let's say I

had six people in a line, I would say

to Rowan, do you think they can run?

Let's see if they can run.

And then we'd go behind.

And of course I've told the

people what we're gonna do,

and then we come really fast.

In the Gallup?

Yeah.

In the middle going.

And the two groups of three go

and they run away to each side.

And then we have, oh, look, we've

got two groups of three, so you know,

six divided by two is three, blah.

And then we round them up.

With farts, multiply six times two,

like a cowboy, a farting cowboy,

you know, and suddenly we have

multiplication and we found that

this kind of thing worked very well.

Are you doing something similar, or is

it, does it happen differently with you?

Monique: Yeah, it, it is,

it is only with a child.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Monique: So there are

no other people, people

Rupert Isaacson: around,

Monique: around?

No.

Okay.

No.

Rupert Isaacson: And how, let's,

so let's say it was something

like the using of the numbers.

Monique: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: Can

you give us an example?

Monique: Yeah.

I can sometimes I put a clock, um mm-hmm.

On the ground.

And I will ask them how, how late it

is when they are already doing that.

So, so it's, it's, eh, also what you also

told put numbers around in the certain

world or I let them search for it.

It's also something Yes.

Sometimes I let 'em search for it.

And I put a number on and I thought,

well go for, look for the same numbers,

and then they have to pronounce it also.

Mm-hmm.

What kind of number do you have?

Sometimes I put also the words under

the number so they have it both.

So they have, and the

number and the words.

So, for example two, then they

also have, have the word two.

Mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

Under the number.

So there are a couple of ways.

I can yeah, teach them.

Rupert Isaacson: And is this generally

with younger kids or is it all ages?

Monique: Most of our till 12 years.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Yes.

And what is, would you say the most

complex mathematical thing that you would

Monique: do?

Mm, that's a difficult question because

every child has his own difficulty,

so, yeah, that's a difficult question.

I cannot really say this, this thing

is really on top of it or something.

No, no.

I'm

Rupert Isaacson: just thinking, for

example, when, when I was finishing

the extent of my abilities with maths,

which are not very big, the process

that I just described with Rowan

was about as much as I could really

do because I'm not a mathematician.

So I then made contact with

a really good mathematician.

Mm-hmm.

Who understood what we

were doing with movement.

Yeah.

With the horse and with not,

and he's this guy called Dr.

Alfred Siegler.

He's German, and he was a physics

professor at the University of Abrook and

an old family friend of my wife's family.

He understood the need for movement,

so we asked him to come up with.

Modules, teaching modules that

we could do for children who were

needing to go to more advanced levels.

Mm-hmm.

And we found it was extraordinary

that we could teach things like how

to calculate the area of a circle

or how to calculate pie or how to

do complex geometry using the horse,

using the forest, using the dog.

Yeah.

And on our website, we have all of

these modules now for people to use.

Mm-hmm.

Because we became frustrated

with our own limitations.

Yeah.

So we began to reach out to other

people for maths and science.

And we found that through

these collaborations we

could do things like this.

Are you, are some of the kids

coming to you needing to learn

some of the higher skills?

And if so.

Are there, are you finding

ways to address that?

No.

No.

Or you just doing fairly

much at the basics?

Monique: Yeah.

Yeah.

Okay.

Yeah.

Most of all the basics.

And it is most of all

that school is too quick.

They, they, they are pushing the it Yeah,

Rupert Isaacson: sure.

Monique: They, they, they want to

learn it very quick, but they don't

understand what they are learning.

So that's the thing.

Rupert Isaacson: Yes, yes.

I agree.

It's, it's so difficult in school.

Yeah.

'cause the, the sensory

environment is wrong.

The kid can't move.

Yeah.

The school smells bad.

Yes.

They're afraid of the other kids.

They're afraid of the teacher.

Yeah.

Everything is going to push

the learning backwards.

Yeah.

Yeah.

And they come out to a place like

yours, suddenly they're with somebody.

Nice.

And there were two nice people.

One of them has four legs.

One of them has two legs.

Has two legs.

Yeah.

They're in a nice environment, as you say.

There's time they can

relax and they're moving.

Yes.

Again, neuroplasticity.

Do you then get reports back from

the school, from the teachers

saying, oh, or from the parent?

This child, yeah.

Made a jump.

Monique: Yeah.

But I also recognize that

school is a little bit.

Yeah,

Rupert Isaacson: sure.

But

Monique: I'm a teacher,

so how is this possible?

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah,

Monique: yeah.

No, it, no.

Yes.

It's,

Rupert Isaacson: they, they, they

hate admitting it, don't they?

It's like, yeah.

So it couldn't possibly be

the lady with the horse.

Yeah.

Monique: Yeah.

But, but you are only a coach.

You are not a teacher.

How so?

That's a little bit yeah.

Sometimes fights.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Fiction.

Monique: Fiction, yeah.

Fiction between the

teacher and me as a coach.

And, and how, how is it possible?

Parents are happy.

They see a kid with a smile and learning,

Rupert Isaacson: I tell

you, it really does help.

When we, we, when we do our trainings

for horse boy movement method,

one of the things that we, we

teach people is the neuroscience.

Yeah.

And when you, you understand you why

the brain is responding in this way.

And you can say to that teacher, well,

it's because blah, blah, blah, and blah.

First you create oxytocin,

then that gets rid of cortisol.

Then this creates BDNF.

BDNF does this in the brain and then

in the BDNF you get these other cells

in the cerebellum that govern Yeah.

Social skills and most

skills, and so on and so on.

And this way we can feed in

the information like this.

That's why it works.

And here are 10 university

studies that prove it.

Yeah.

Yeah.

What what really helped us last year

to 20 40,024 was a PhD was published

into one of our programs, which

is called Movement Method, which

is the one we do without horses.

That's now in schools.

And but it's based on everything

that we do with horses.

It's just we realized that people

needed, you know, something

to do, you know, at home.

And we never thought that it would

end up in schools, but it did.

And then a PhD was done on Movement

Method in schools in Germany.

What were called UNK schools was

burning Point Schools where they had

an overwhelming number of of refugees.

And there were Ukrainian children

with Russian children fighting.

There were Syrian children fighting

with Iraqi children and so on.

And Movement method came in and

didn't just create better academic

and better behavior outcomes.

But also, this was

interesting, the teachers.

Wanted to stay in the job.

There was better teacher satisfaction

and fewer teachers leaving the job

because we did the study over some years.

Yeah.