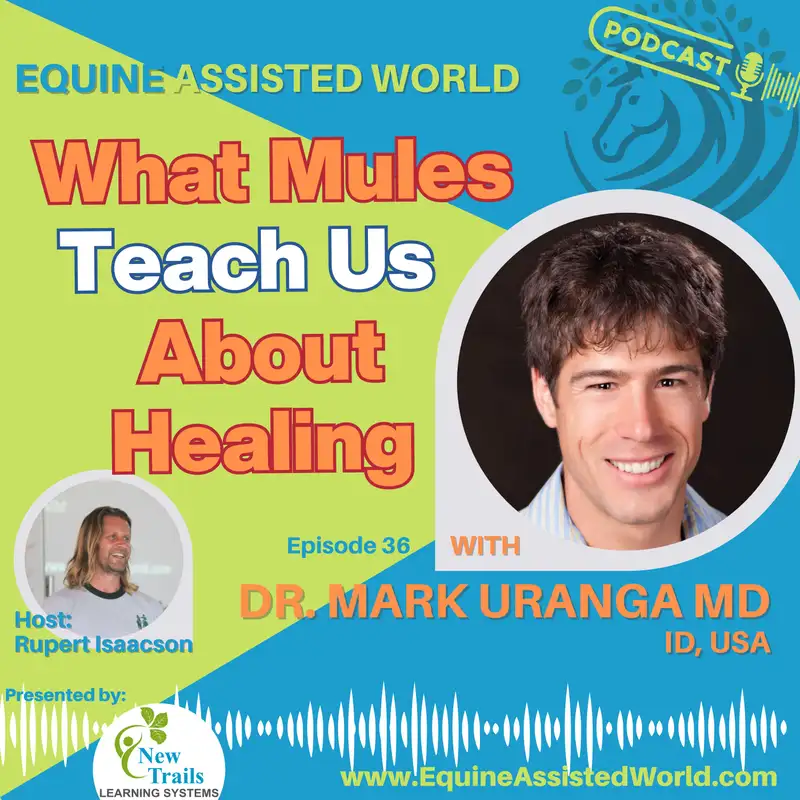

Resilience, Mules & Pediatric Wisdom: Dr. Mark Uranga on Community, Horses & Healing | EP 36

Rupert Isaacson: Welcome

to Equine Assisted World.

I'm your host, Rupert Isaacson,

New York Times best selling

author of The Horse Boy, The Long

Ride Home, and The Healing Land.

Before I jump in with today's

guest, I just want to say a huge

thank you to you, our audience,

for helping to make this happen.

I have a request.

If you like what we do, please

like, subscribe, tell a friend.

It really helps us get this work done.

As you might know from my

books, I'm an autism dad.

And over the last 20 years,

we've developed several

equine assisted, neuroscience

backed certification programs.

If you'd like to find out more

about them, go to newtrailslearning.

com.

So without further ado,

let's meet today's guest.

Welcome back rockers.

We have Dr.

Mark Uranga here from Idaho.

And if you're worrying, wondering,

not worrying, wondering where

the name Uranga comes from.

It's Basque, Basque Spanish well,

so Basque French, which is this

interesting corner of the Atlantic,

semi Celtic Fringe in Europe.

And some of you may know that there

was a large scale immigration of

Basque Shepherds to the United States

in the 19th and early 20th century.

So there is an interesting subculture and

I went and did a training in Idaho last

year and was lucky enough to meet Mark

who brought his mule to the training.

And the mule was the

Star Fi show for sure.

And, mark intrigued me because

as a doctor and a pediatrician,

he has some interesting insights

on the work that we all do.

And I think it is always useful

for us to know that doctors

actually do support this stuff.

And, you know, don't, don't just

roll their eyes and say, well, you

guys are just playing with ponies.

So it's, it's nice that we have a

chance to get 'em on here and ask him

why, why does he think that equine

assisted stuff is, is, is valid?

What does it do?

And so on.

So without further ado, mark, who are you?

What do you do?

And yeah, take it from there.

Mark Uranga: Well, thank you first for

all the work that you do to advance the

idea that there's growth to be had for,

families and for children outside of a

clinical model, specifically speaking,

one confined to buildings and to

people with different types of degrees.

My background is, as you mentioned,

as a Basque Idahoan, and I don't

know that I can separate the two.

I was born and raised in Boise,

Idaho, and from an early age,

thought I might be a veterinarian.

At about the age of 20, when it was time

to take the test for veterinary school or

medical school, I felt drawn to a little

bit richer involvement with families and

complexities of human-centered medicine.

And from there I went to medical

school and trained in pediatrics,

and I've been practicing for about 14

years in the Boise area, a year or two

before that in New Hampshire and the

richness of the clinical environment.

Is something that I treasure every day.

It is not always the place to make

inroads for people that struggle to

sit still or to be in a confined space.

But it is a place that about

20 times a day, I test the

interactions with children,

adolescents, and their caregivers.

And the, the draw of that for me was

initially to show parents how interacting,

even in moments of time can really help

children feel more safe, more comfortable.

Clearly the, the pediatrician's office,

if any of us remembered, it's mostly

about shots and it's mostly about

inconveniences and fear, either because

of going with illness or getting a shot.

And some of our training, I was

lucky enough to have mentors who.

Emphasize the value of

making a child comfortable.

And what I quickly found is that a

comfortable child is a more reliable

patient, somebody that I can learn

their nuances much more quickly.

I think that having been drawn to

pediatrics, it came from a background

where I was lucky enough, as you

mentioned, to grow up in a kind

of a community within a community.

So in, in current life, a lot of

us aren't around children anymore.

And I was lucky enough to go to a

daycare from eight weeks old to about

12 years old where an Basque woman

modeled the interactions with children.

And I was surrounded by little kids at

a time where I didn't have necessarily a

lot of cousins or 10 siblings or anything

like that, but that early experience

helped me be comfortable with children.

So.

As I was modeling that in, in clinic,

it, it's become more and more clear

that this communication that we

develop in moments within a, a clinic

visit, really makes a difference

in the interactions with a child.

Rupert Isaacson: You said

you were lucky enough.

I, I don't hear many people say, I was

lucky enough to go to a daycare, you know?

So clearly that was a positive experience.

What is special do you think about the

Basque approach to children and family?

Mark Uranga: It's a, it is a

great question and one that I

I've had a couple opportunities to

explore that well think growing.

The Basque culture has always been a

little stubborn and has also been defined

by a language that doesn't easily, it's

not a romance language by background.

So the, the overlap with invaders

or visitors from Roman elsewhere was

more problematic for the conquerors.

And so there's sort of this history of

a, of a little bit of nuanced and, and

more isolated approach to, to community.

And within that, the, the family

becomes a really important kind of seed.

And so as many immigrant stories are

families coming over, came with different

attachments different sponsors and

the sort of things that allowed them

to start to thrive in our community.

And as I grew up, my

grandfather was an immigrant.

We're so, we're removed from the immigrant

experience per se, but the, the culture

that that followed, that was one in

which grandparents knew grandchildren and

grandchildren were friends with cousins.

And, and so the modeling and that.

Combined ability to reach out yet feel

protected is something that I think is

really well modeled in our community here.

Now, having maintained a connection, the,

the very social, the hyper social model,

I would argue within vast society really

is one that encourages a give and take

at the daycare and younger age level.

And simply by I suppose absorption

of those ideas, it just felt

more comfortable, I think, to be

around children and to allow those

children to drive towards their

areas of interest and and comfort.

Whereas in a, in a group that's maybe

a little bit more nuclear family

or family centered, where it's been

kind of gratifying or I suppose it's,

it's been held up as a standard.

A single adult or maybe two adults

will provide the role modeling and the

limits and the interactions outside

of the family can be more limited.

I think a, a community oriented upbringing

allows people to see those different

models and to feel more comfortable

within a time where, you know, an

8-year-old is carrying around an eight

month old and these things that, that

don't always happen so much anymore.

Rupert Isaacson: Is that was, that

was what was going on at your daycare.

Mark Uranga: Yeah.

Yeah.

Certainly.

That's very some of that unusual Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: In our culture.

Mark Uranga: Yeah.

Quite unusual in the American

culture that even in, within many

daycares it's, you know, the kids

under one year and then one to two.

Yeah.

They do a different thing 'cause

they're walking and more mobile and

then there's this kind of napping

age and the age after kindergarten.

So yes, it, it does

isolate those peer groups.

Rupert Isaacson: It's interesting,

I mean, it seems to me what you are

putting a finger on here is tribe.

Mm-hmm.

Would you say?

Yeah.

Mark Uranga: Yeah, yeah.

And, and tribe is something that.

Has value and has downsides.

But I think that the, the value

in tribal upbringing, as it were,

is that trusted adult that adds

something to what a parent's offering.

The increasing responsibilities

that you touch on in a lot of your

work, the, the learning that goes

along with that so that it's more an

experiential approach to especially

social problem solving, I think.

Rupert Isaacson: Do you feel also that

I mean not all tribes are nice tribes,

but let's assume that you had a good

exp it, it seems that you had a good

experience so, that this tribe is good.

Do you feel that the Basque

community is particularly good

at letting things be child led?

And if so, why might that be?

Mark Uranga: I, I do believe that and.

Much, much more clearly in the,

the current European bas, the

ones who are still in, in Spain

and, and somewhat in France.

And I think that's because they want to

keep talking to their adult friends and

let the, the children have their space.

I think there's that recognition

that their safety mm-hmm.

A, a given plaza or a, a shared common

space where things are safe, but there

are, there are conflicts, there are

sharp edges, you know, there are things

that, that scrape knees and, and hurt

feelings and, and those sorts of things.

But they're in a, in a location where

they can recover from that with a

still, with a feeling of, that's

Rupert Isaacson: interesting.

So, so why do you feel that

that kind of tribal model builds

resilience then, as you say, so,

scrape knees and hurt feelings.

You know, we are so shy of that stuff now.

We, we think we, you know, people

are really quick to jump to

immediately to trauma, you know?

Yes.

Rather than, and then of course, now

there's interestingly a movement coming,

saying, well, yes, but there's a whole

kind of growth after trauma thing.

Mm-hmm.

You know, getting scraped me

in and hurt feeling as a kid

isn't necessarily traumatic.

It might be unpleasant, but it's also

kind of necessary preparation for the,

for what we're gonna meet in the world.

What, again, just I'm intrigued by

your experience as a basc, um mm-hmm.

And then how this has informed

your approach to pediatrics and the

equine assisted world, which we're

gonna come back to in a minute.

But I do think this is

great context for people.

'cause not everyone is coming out

of this kind of tribal background,

particularly in the west, you know,

so you're quite unique in this way,

and I think there's a lot to offer.

I want to sort of mine

that vein for a while.

So when you say sharp edges,

you know, scrape knees hurt

feelings, but in a safe space.

Can you, can you elucidate a bit

more on what you feel the value of

that is and what that leads to in

adolescence and adult life for people?

Mm-hmm.

Mark Uranga: Yeah.

I think that, that we have lost, that

graded did experience of living of the,

the things that I learn where I'm not

protected, but where I can recover.

So there's, as you mentioned, that

the trauma literature, which is an

area that affects d different people

differently and can be expanded by its

scope to include things that are more

an opportunity for growth in some people

than an opportunity for destruction.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

Mark Uranga: And what.

Even within the, what I'll call allopathic

medical literature, the literature

that's largely informed by MDs and people

with degrees and these sorts of things.

Um hmm.

The, the paradigm about mental health

or, or resilience does start to include

some ideas that the practiced resilience,

the, the times that somebody had

recovered from trauma, as it were Yes.

Is that, is it builds that resilience.

An example is, is well known within

pediatrics now, where children who are

seeking an independent experience, let's

say in Idaho, maybe walking to the store

to buy some tic-Tacs or whatever it

is, you know, as a, as a trauma focused

society, our first thought would be cars.

Bad people.

What if they don't have the right change?

All these sorts of things.

As a resilience associated paradigm,

we look at that as the opportunity

to to interact with somebody that

might cut in line to, to have to

figure out the math on their own.

And, and these early steps are the

same things that, that apply when a

high school senior doesn't get accepted

to their number one choice of school.

And if everything has been bubble

wrapped up until that first negative

experience, then there's no, there's

no practice, there's not been a pattern

of rebound that a family can, can mine

and, and then can take advantage of.

Rupert Isaacson: It's really

interesting because, you know, there's

a lot of talk, you know, people

tend to think in extremes and so.

In the sort of trauma informed world,

there's also this idea of adverse

childhood experience, you know, and,

and that this lessens the chances

of, of success and thriving later.

And, but what I find interesting

about that is so many of the people

I know who do thrive, have had

adverse childhood experiences.

And then is a scraped knee falling

out of a tree, falling off your horse,

breaking a limb, that sort of thing,

an adverse childhood experience, or is

that a just planet earth experience?

Like is have we allowed trauma

and adverse experience to now?

Become a sort of abused term that

has now sort of bled into normal

experience so that now we are afraid

of normal experience, you know?

Yeah.

Just talk to us a little bit about

the dance there, psychologically and

emotionally for the, for the sort

of, for the young growing human.

Mark Uranga: Yeah.

I think one of the best areas I see

that it's just so concrete, and I think

all of us can relate to it, is the, the

child who falls in front of a parent and

what is the message sent by the parent.

So two years old, they trip on

their own feet, and is the response

concern, is it overconcern, is

it on the more negative side?

Is it mockery or something else like that?

The, the way I can predict, not based on

the fall, how that child will react, but

based on the parent's reaction, right?

So the, the mechanism is, is

immaterial to the response and.

That is where I get back

to the sense of safety.

Like you were talking about a sharp

edge, yet a safe recovery from that.

So, the child who falls and whose,

whose parent is like, oh yeah,

let's get up and keep moving.

Or too bad that happened, or, or

make a joke about not breaking

the floor or whatever it is,

you know, they, they move on.

But the, the one who's concerned

or so sad or, or anything that

child is, is much more likely to

escalate based on the signals they

receive from their trusted adult.

And I think that getting, moving forward

as we build these patterns, we basically

have experiences that are pre-verbal

and through general development.

We build upon those verbal

experiences and, and our emotions.

And yes, we add words to them, but in

the background and experience is usually

going to elicit an emotion first.

So if our experience has been to

rebound, then our first response

to a lost job or the death of a

loved one is that sense of rebound.

If it's, if it's been signaled

to us that those are traumas,

then, then they become traumas.

And I'm fortunate, I believe, to

have models in the community and

in, in parents and in others where

the, the rebound is emphasized.

And I think as you look at

this variability of what do we

call an adverse child event?

What do we call a trauma?

And the response to that as you.

Basically I, I'm a pediatrician.

I love to think of all

people as grownup toddlers.

Toddlers are just more honest.

I certainly am

Rupert Isaacson: in

that, in that category.

I've never really stopped being a toddler.

I just got bigger.

Yeah.

Mark Uranga: Yeah.

Right.

And, and it's true of all of us.

Some of us embrace it and so all

more power to you, Rupert, to have em

embrace that, but we have that response.

Rupert Isaacson: It's civil to deny

Mark Uranga: we have that response.

So we move forward from that based on

our experiences and it's all practice.

Rupert Isaacson: Do you feel that

this type of, this emphasis on

resilience in the Basque community?

I see.

I'm, I'm half Jewish.

I'm half Ashkenazi Jewish, and

obviously in our heritage, even

though I look like a Viking,

because my mother's side is Viking.

But my father's side is Ashkenazi Jewish.

My father looks like Saddam Hussein.

And we had this joke when they were

looking for Saddam that, you know,

I was gonna show up at the Pentagon

with him, say, look, I've got him.

And then he and I would

split the money, you know.

But the Ashkenazi experience was

pogroms, you know, it was you know,

always have to have one eye on the exit.

'cause you never know.

And how the, the, the more you

thrive as a community mm-hmm.

The more likely it is that some

busted somewhere is gonna come

along, decide to take it from you.

Yep.

So, and your community in a

nasty, bloody kind of a way.

So you.

Better kind of have options.

So you want to have family and

you wanna have family in other

countries and other cities so that

you've got lines of, of, of exit.

And if you, if you, there's always

more of them than there are of you.

So, and there is no homeland.

Now you, on the other hand, come from a,

the somewhat the opposite, but mm-hmm.

So there is a homeland.

Yeah.

However, there's lots of

invaders, you know, so.

Mm-hmm.

For those, for those who dunno,

their European history, everyone on

their dog has tried to invade the

Basque territories at some point.

Why?

Because they sit at the, at a

very, very sort of strategic

and fertile and pleasantly

climate juncture of the western.

You know, European Atlantic right

there, sort of at the top of Portugal

and Spain and the southern bit of

France, and it's jolly nice there.

So anyone who ever came through

went, oh, it's nice here.

I think I'll have some of that.

And the mountain people living there

who, as you said, you know, were

speaking a language that predates

all of these other European languages

and have been there seemingly as,

as a, as a, as a, as a composite

community, much, much for millennia.

Despite all of these tribal migrations

going across Europe and measure, hold

their own in this mountain fastness,

yet everyone tried to take it from them.

And the fact that they are still

there is somewhat of a miracle.

It's, it's not dissimilar to the

Kurds up there in northern Iraq

and Eastern Turkey and so on.

Somehow managed to hold onto that

area despite, you know, it ridiculous

amounts of, of, of, of assault.

So do that can create a certain

bitterness or it can create a certain.

Let's seize the day and live type.

And, and, and we've survived this

long, so probably we'll survive again.

And from the pogrom point of view

is, well, they killed so many of us

that we sort of whittled down to,

you know, the special forces now.

So, you know, we're

quite good at survival.

Mm-hmm.

Do, do you feel that that is there,

is there a bit of a heritage that way?

Like you bit the Native Americans

of Europe, of Western Europe in a

funny way, you know what I mean?

Yeah.

Just, just mm-hmm.

Talk through that idea of resilience and

survival a little bit for us before we

go into actual equine assisted stuff.

Mark Uranga: Sure.

Yeah.

I, I think you get to both of

those, having a creation story

or a creation myth, depending on

how you'd like to think about it.

Oh,

Rupert Isaacson: go on.

That's

Mark Uranga: interesting.

The, the creation story.

We all have a creation story.

I, I love the, the nexus

of how my creation story.

Interact with the creation

story of the Idaho Basques or

the, the Basque country itself.

Your story of migration continuing

as long as written Torah stories were

placed, the, the Jews were on the

move, and you've moved from South

Africa confidently to, to Germany and,

and how we each fit in these stories.

The relationship, I believe to, to

parenting and pediatrics lies in a

concept of what is called authoritative

parenting, not authoritarian author.

Author parenting.

Yeah.

Okay.

How is that different from

authoritarian Exactly.

So, and different from passive

parenting or permissive parenting.

The middle ground is that which recognizes

the variability of a child and does

not force upon them certain things, but

provides the background, the framework.

From which a child essentially

defines themselves.

So whether that definition is in

contrast to the family expectations

or in alignment, there's still a

foundation that's provided with that.

So the, the idea being that a family

exists within a community, a community

of, of basks is, defines themselves

as partly stubborn, quite social very

committed to their shared background.

And within that BASC community, defining

our family as being committed to each

other, having a shared background and

being somewhat stubborn or persistent,

those allow for our children to consider.

A model that is either in tune with

their growth or in contrast with that.

And, and, you know, all communities

have their rebels or their black

sheep, and those people are equally

as defined by their community.

I think where it provides that foundation,

there's a little bit less wallowing

around for who am I or what am I?

So where we see that, I think breakdown

in a community or in permissive parenting,

what can happen is that a child lacks the

tools to discern largely right or wrong

because somebody is, is just following

the child without that bigger view of

a goal in mind or an ideal per chance

or, or however we choose to define that.

So they, those, those children

can kind of cast about thinking.

At two.

Is it okay for me to throw food

all over and yell at mom and dad?

Or is it not okay?

And when I get to be four and five,

maybe I can do the same thing to my

teachers, and why would I expect to

follow the, the laws when I'm 15 and 16?

And, and, and lacking that experience,

that kind of defined set of values can

really lead kids to, to place of anxiety

or kind of driftless experimentation.

Whereas kinda getting back to the idea

of how a community defines itself,

itself, you're absolutely right.

As you mentioned earlier, some tribes

are not all good guys, as it were.

And, and yet if a, if a child is

given that experience within a, a

tribe of, of learning, then from the

outside world that, oh, that life is.

Better or different, they're

still able to contrast that

to their, to their background.

So I'm not sure if that

gets entirely to the idea.

Well,

Rupert Isaacson: yeah.

The, the, the question's also about,

I think it's, it's really good for

people to have a clear idea about

authoritative versus authoritarian.

Can you just define that?

And then I want to go to follow the child.

'cause as, you know, follow the

child is one of our, you know,

prerequisites within the work we do.

But yes, it's not follow the child

aimlessly, it's follow the child.

Exactly.

Because someone isn't speaking.

So you're not there to, if you're

not there to observe, then Uhhuh

you haven't got much to go on.

And you need to follow

what motivates people.

And, and, and that is true

whether they're speaking or not.

If you don't follow what motivates

them, then you are in conflict.

Um mm-hmm.

But.

And, and, and authoritarian

to me is defined by conflict.

You know, it's mm-hmm.

I, I grew up, not with my own family,

but with the school system that I went

through a very, very authoritarian mm-hmm.

System.

It's interesting, you know, I meet

conservative Americans and they meet

me and they think, oh, you're such a

hippie as like, you have no idea what

auth, what conservative really is.

You know, you, if you'd gone through the

school system that I went through Yes.

Where we were beaten, you know, daily,

and we were all in the military and we

were all, you know, it, it very different.

Very, very different.

Very violent, very, you know, blah, blah.

Okay.

But all that aside, it was authoritarian.

And so what it meant was that the,

there were, there were two things that

designed the school system, de defined

the school system I went through.

One was that they said, you are all

or you boys are going to, 'cause

it was only boys are going to be

in competition with each other.

We are going to set you into

competition with each other,

which means some of you will fail.

And they, they were saying this to

you at age 11 and we're gonna break

you down so that we can then build

you up and give you privileges later.

Mm-hmm.

Why would they do that?

Well, they would do that so

that a hundred years ago people

might go out and run the empire.

And that was creating an officer class

where people would go and sort of with

both a sense of personal confidence and

a sense of absolute belief in the system,

go and sort of die of malaria in the

Sudan age 30 while trying to administer an

area four times the size of Germany, you

know, just one province and deal with the

tribal wars and this and that and do, and

have the kind of resilience to do that.

But there would be a wastage, and you

saw this wastage also happening in sort

of World War I where the officer classed

the young officers first over the trench.

You were supposed to inspire

the, I say the average.

Average lifespan, you know, of a

young officer in World War One, in the

British Army was six weeks, you know,

because you had to be first over the

lip of the trench and so on and so on.

However, those that survived would then

become the building blocks of the empire.

And you can see how that

worked very well for the people

that were running the empire.

You, you, you needed a group of people

like this, but what it meant was that

at the bottom line, if you bucked the

system, if you said, I don't really

want to follow these particular rules,

you were met with violence immediately.

That it was, it.

So if you were going to go against

the authority in any way, it was

instantly physically violent.

And what a lot of us learned was to

actually cope with that and to say,

Ooh, actually I can survive that.

And.

Now, what are you gonna do?

You know, because now

I'm not afraid anymore.

However, there were others who

were completely destroyed by it.

So as obs, you know, I observed

this growing up and thought, well,

there has to be a better way.

And so when you use the

word authoritative, I like,

and I'm intrigued by that.

Could you, could you explain really to

your, what we, we can, I think we can

understand what authoritative means

but au sorry, what authoritarian means.

Right.

But let's go to authoritative.

Mark Uranga: The idea of an authoritative

parenting model or community for that

matter, really, is that there's an,

there's an expectation, there's a, a

standard that we might move toward.

It is a model that allows.

For the ex exploration that you

might think of with a permissive,

permissive parenting model.

But when, but when that child turns

to the parent, to the community to

look for an answer that they don't,

they truly do want an answer for,

they're looking for assistance.

It's willing to provide that.

Whereas a permissive parenting model

kind of renes on that responsibility, you

have a, an underdeveloped brain or person

coming to you looking for an answer.

And with a permissive model, it's a

reflective, let's say well, should I have,

should I have a cookie or an Apple mom?

Should I have a cookie or an Apple dad?

Should I have a cookie?

And Apple, a truly permissive

parenting model, would say,

well, what would you like?

Well, with food engineering

being what it is, it's a cookie.

With a, with an author authoritative

model, it would be, I think an apple's

gonna make you feel healthier, or I

think you should start with an apple.

It's, it's offering that guidance

where it's due, and ultimately all

of us look for some structure there.

We are not living in an anarchy.

You and I would like to go through a green

light thinking that somebody is not gonna

drive through the red light, you know?

Yeah.

There are clearly levels of these,

but what, what the authoritative

model provides is it gets a little

back to that safety as well.

Like if I'm lost, if I'm casting

about, I can provide you something

that will provide you comfort

or safety in the longer term.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

It, it, I was writing, I wrote a

note here as you were, it, it sounds

to me like you're talking about

service to the community that mm-hmm.

First, there's the idea

of what serves you.

So do I have the cookie or the apple?

You know, so my, my answer to that would

be, I totally get why you want the cookie.

Mm-hmm.

I want the cookie too.

Yeah.

And there will be cookies.

Don't worry.

Yeah.

There will be cookies.

Mm-hmm.

However, maybe not those cookies.

'cause those cookies are full of shit.

Right.

But how about these cookies?

But before we have those cookies,

let's talk about the apple.

Now, I'm not going to force

you to have the apple.

Right, but look, I'm gonna have

the apple and what if we had both?

What about apple and cookie?

How about that?

You know, and then I would be

prepared with, to go through a

certain amount of, nah, nah, nah.

Because I have the same Nah.

Inside me.

So I, you know, I'm, I'm not gonna

say someone else shouldn't have it.

But at the same time, I would

take a slightly humorous approach

to that and say, look, but, and

also sympathetic, like, I get it.

I get it.

They've marketed these cookies to

us and, and we are driven by sugar.

Yeah.

So of course you want it, but why

don't we also have this apple as well?

And I would hope that with that continued

thing and, and say one, you know,

there, there's gonna be no force here.

There's gonna be no, you

must have the apple or Right.

There'll be some sort

of terrible consequence.

Mark Uranga: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: But as you say,

the cookie may not, may make you

not feel so good and you know, maybe

you need to go through that feeling.

Mark Uranga: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: And when you go

through that feeling, then I'm

still here with the apple, you know?

Mark Uranga: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: And someone will

say, well, Ruper, why don't you

just tell them to have the apple?

Is that because, because

then, because then the cookie

becomes a holy grail, you know?

Exactly.

And so, you know, how you tread

the line between permissive

and authoritative mm-hmm.

Seems to me about what serves you best.

Mm-hmm.

Right.

And if you can appeal to the child

to say, well, what's in the child's

best interest on the end of the,

and then clearly mom and dad are

thinking about my best interest

then is it a sort of logical thing?

For me to think about the best interest

of the community, the family, and Right.

The, the note that I took there

is, is service to the community,

what actually provides for

happiness and fulfillment in life.

Mark Uranga: Yeah.

I think that evidence about that is, is

increasing in a way that just makes a

lot of sense when you have a, a community

and an evolutionary perspective that

shares resources or serves each other

when we were all just barely scraping by

and caves are on a Savannah or whatever.

Those, those, what people call selfish

genes do replicate by, by providing

that service, there's the evidence

surrounding a sense of fulfillment

is universally supportive of.

A sense of service or commitment or

attunement or any of these sorts of

connection sort of ideas that when

we can place a child in, help them

find their place in that world.

I think a lot of the, the work that

you share about experiences with hunter

gatherers and these sorts of things,

these are very concrete contributions

that children make at a small age.

And their sense of attachment is, is

so much more community focused than our

world where it's in a, in a generally

speaking western world where we have

work to do, that's specialized work.

We have bills to pay that are, you

know, technical and we have projects

to do that are too skilled then.

Then the child feels a little isolated.

They lack that sense of service and

their, their kind of drive for that

leads them to look for attention.

That, that I think, often we wrongly

think is attention that wants play or

immediate gratification, whereas that

attention seeking that's so hardwired

is about finding that attunement,

finding that connection and then that

safety that I can do these things and,

and somebody's with me and watching

me and helping me through those.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

You know, I guess in the old days we had,

although, you know, we, we didn't grow

up in hunter gatherer community, sadly,

where absolutely the, the community,

everyone's in service to the community.

But two generations ago.

Most people were growing up in some sort

of family business, family farm family,

you know, or not most, but certainly many.

Mm-hmm.

With kids being included

in what was going on.

Maybe they wanted to, maybe

they didn't, but they were

certainly included, you know?

Mm-hmm.

And they were skilled from quite an

early age in not just the physical or

mental competences required in the family

tailoring business or the family farm, but

also the financials and the economics and

the balancing the books and the mm-hmm.

You know, I've got to buy in this amount

of feed and fertilizer or this amount

of cloth and, and you know, needles and

balance it against, you know, mm-hmm.

Blah, blah, blah.

And that of course seems to

have gone, you know, that, that,

that now, barring very few.

Sort of isolated communities or people

that are just lucky enough to grow up

in certain types of family business.

Now the family farm, it, it's, it's

something that almost exists in myth now.

You used twice in the last five

to 10 minutes the word attunement.

Attunement.

Mm-hmm.

Right?

And this is a word which many of, many of

the people who listen to this podcast also

listen to Warwick Schiller and Warwick

Schiller uses the word attunement a lot.

And those of you who listen to l Leanna

Tanks podcast where she's talking

about the use of attunement with

working with the criminally insane.

And how that's, if you haven't

heard that one, by the way,

listeners, you've gotta go back and.

Find Leanna Tank's interview.

It's, it's, it's, it's meaningful and

there's a lot in there that helps us all.

What do you mean Mark by attunement and

what should we understand from this term?

Mark Uranga: Well, yeah, I, I lean

heavily on, on Warwick chillers

shorthand, which he always de, he

describes as being seen, being heard,

feeling, felt, and getting gotten.

And the first parts of

that are, are very sensory.

So they are and again, with toddlers

in my life every day, I, I always

think of the toddler model when, when

a toddler approaches me, do I look at

them or am I seeing what they're doing?

When, when I come into the room,

does the toddler turn from me?

Do they make nonverbal cues

that, that they're concerned?

And again, I just think toddlers

are honest people, whereas the

rest of us have this overlay of

politeness and what should I do?

And these sorts of things.

Yet we signal these things

as well, without a doubt

as we talk to other people.

And the idea of attunement is, is with

toddlers, with mules, with horses is

that awareness that is not verbal.

I think that it can have a verbal

overlay, but the richest attunement

with adults as well is, is more of

a nonverbal, sort of a, of a dance.

And the, the role that that

plays in, in my life is.

Again, 20 times a day I enter a room and

I could have a kid that's gregarious, a

kid that's hungry, a kid that was just

told they can't be on their phone or

within, within moments, their physical

reaction to me informs which way I go.

Are they already goofy and do

they want me to make jokes?

Are they quiet?

Do they want me to use a quiet voice?

Do they do I see that their shoes

light up and they want to jump up in

the ground, up and down on the ground?

And when a child has that sense of being

seen, then they can start to develop

a sense of comfort and safety and move

away from that protective stance that

the stranger danger that's typically

going to accompany at least a physician

visit, but often any other new adult.

Rupert Isaacson: That's brilliantly put.

I think you answered it

incredibly succinctly.

The, the nonverbal cues which

we learn through horses really,

really help us with the nonverbal

cues with our fellow monkeys.

And ultimately our fellow monkeys are

much more dangerous than our horses are.

You've used the, you've referred

to the word stubborn quite

a few times as well, right?

And you, you stubborn with the

bass community, but you seem to

have referred to it as a positive.

Mark Uranga: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: You've also

now included the word mule

Mark Uranga: and,

Rupert Isaacson: I know you as a

handler of a very good mule that

I was lucky enough to meet when we

were doing some training together.

I wouldn't say that Mule was stubborn.

I would say that Mule was, was a

hundred percent present and cooperative.

I wouldn't have wanted to make that

mule do anything it didn't want to do.

But I wouldn't wanna make any

equine or human do something

they wouldn't want to do.

But nonetheless, you, you, you've sort

of gone bask stubborn mule in your life.

Talk to us about that.

Why have you gone for mules?

Why do you feel stubborn is good?

What do you mean by stubborn?

Because people have different

meanings around that word.

And then talk to us a

little bit about mules.

Mark Uranga: Yeah.

I, I use stubborn as

you picked up with it.

Some sense of pride,

some, some sense of irony.

It's, it's obviously quite

close to persistence and okay.

Rupert Isaacson: Perseverance, perhaps

Mark Uranga: perseverance,

persistence, stubbornness.

And it just

Rupert Isaacson: mountain people.

You don't give up.

If you're in the equine assisted

field, or if you're considering

a career in the equine assisted

field, you might want to consider

taking one of our three neuroscience

backed equine assisted programs.

Horseboy method, now established

for 20 years, is the original

Equine assisted program specifically

designed for autism, mentored by and

developed in conjunction with Dr.

Temple Grandin and many

other neuroscientists.

We work in the saddle

with younger children.

Helping them create oxytocin in their

bodies and neuroplasticity in the brain.

It works incredibly well.

It's now in about 40 countries.

Check it out.

If you're working without horses,

you might want to look at movement

method, which gets a very, very

similar effect, but can also be

applied in schools, in homes.

If you're working with families, you can

give them really tangible exercises to do

at home that will create neuroplasticity.

when they're not with you.

Finally, we have taquine

equine integration.

If you know anything about our

programs, you know that we need a

really high standard of horsemanship

in order to create the oxytocin

in the body of the person that

we're working with, child or adult.

So, this means we need to train

a horse in collection, but this

also has a really beneficial

effect on the horse's well being.

And it also ends your time conflict,

where you're wondering, oh my gosh, how

am I going to condition my horses and

maintain them and give them what they

need, as well as Serving my clients.

Takine equine integration aimed

at a more adult client base

absolutely gives you this.

Mark Uranga: Yes.

Yeah.

So the reason I like to lead

with stubbornness is because

of the baggage that it has.

Yet we flip the idea to persistent

and all of a sudden to perseverance

all of a sudden this is an attribute.

Right.

And I suppose it's the goal

to which that's directed.

The, we, we talked about

creation myths and the idea that.

The Basque people would be stubborn

enough to run off the Romans and

to stop the Moors as they came

up across from southern Spain and

Rupert Isaacson: Charlemagne and the

Franks and everyone, everyone had to go

the vi goth, the vandals, whoever it is.

Yeah,

Mark Uranga: yeah.

So, so it, it comes to define that

group and the mule I know you have

listeners of, of all backgrounds,

and it's always fun to, to step

back to the, the making of a mule.

A mule is the product of a male donkey,

a jack, and a female horse, a mare.

There can be a converse, which

could be a hiney, which is a

female donkey and a male horse.

But the vast majority

of hybrids are mules.

And the mule in our life has the value

of being one of the most surefooted

of the equines in the mountains.

So Idaho has.

The largest wilderness area within

the contiguous 48, the lower

48 states as it were in area.

I've been lucky to move through as we

talked about movement and experiences.

Mm-hmm.

As hunter gatherers, I've shared those

experiences with many people in many ways.

And as our family got into equines

that lure to be able to safely

travel through rugged country is

what drew us to work with mules.

And the, that stubbornness is

also a sense of self preservation.

So the background of the donkey

is more a mountainous breed to be

around cliffs and other places where

standing their ground was an option.

And it was not the steps of Asia where

flight is always the survival mechanism.

So the mule.

And we, we get the pause,

the stubbornness as it were.

And, and I remind myself and my

kids that, that we want this in

our mules because their sense of

self preservation keeps us safe.

And I think one of the fun things that

I've come to learn, we, in our family,

we have a, a Navajo pony, we have an

appaloosa horse, we have a mule, two

mules one of which may or may not be a

Henny, but those, the mule will pause.

And usually with the attunement that we

have developed, carry on for example,

through a goalie that maybe smells

a coyote or through something that's

changed in the environment from when they

walked out to when they walked back the

horse, our ponies, there are times where

we will use them to lead because they.

Again, with that attunement that

we've built, we'll be willing to

override their sense of hesitation

to try to move through something.

Whereas the value of the mule in our

area is really to take that pause.

They see all four feet and they

can move slowly and and safely

through those environments.

And Sam came to us as a, a purposefully

bred mule who lived with a, his previous

owner for 20 years approximately.

And the time you saw

him, he was 27 and Wow.

Wow.

He looked so good.

Yeah, he looked so good.

And he as you know, he's,

he's a willing mule.

And, and that's because what people

have ha have asked of him in the past

have been safe questions have been

trustworthy questions, largely speaking.

He's not been forced, he's not

been compelled to do something and.

It's, I, I, I hear this in your

background from a military school of

breaking somebody down and building

them up and the old breaking a horse.

You know, I guess it still exists

somewhere, but we've been lucky enough

to have models and yeah, mentors

who start horses who, who, who meet

the horse where they are and, and

move forward with that goal in mind.

And, and Sam came to us largely in that

path and, and we've been lucky enough

that Samuel continues to help us grow.

I love that he's

Rupert Isaacson: called Samuel.

Yeah.

Right now let's go back to

the word stubborn, though.

Stubborn can mean in its pejorative

sense, in its negative sense.

Unwillingness to change basically, right?

Unwillingness to take on new perspectives,

which of course is not a way of self

preservation because you know, when the.

When, when the Vikings or whoever are

coming over the hill, you can't say,

well, they're not coming over the hill.

Or, you know, I've lived here and this

is my grandfather and my grandfather

before him was on this land.

And yeah, I know dude, but

there's like 8,000 dudes coming

over the hill waving xis.

So you know, how about

we make a plan B or C.

Mm-hmm.

Or D.

Mm-hmm.

And the people that could make

the plans, you know, A to e were

more likely to survive than the

one who said, I will not move.

Mark Uranga: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: We love to think of the

kind of Gandalf, you know, you shall not

Mark Uranga: pass,

Rupert Isaacson: you know?

But then again he did get killed

when he did that with the bowel rock.

And there might be a time for

that type of self sacrifice.

And of course, you know, we, we also

assume that Gandalf is coming with

a certain amount of self-confidence

of magic behind him, and he

happens to know the king of the

Eagles who happens to come along.

So, you know, he's got,

he's got, he's got backup.

And he wouldn't have stood there

with his stuff and done that if

he didn't feel he had backup.

So.

You are not using the word

stubborn in that pejorative way.

Yet nonetheless you are using that word.

And I feel that when we're

working with particularly

people on the spectrum mm-hmm.

Who are in the less flexible stage of

their life, and I talk about this a

lot with my son Rowan, who's 23 now.

He's here in the house.

You know, he'd be the first

to come up and say yes.

When I was young, I was

incredibly inflexible.

I made it extremely stressful on

everybody around me and myself.

It's just that I didn't have any choice

in the matter because that's where my

brain and my nervous system were at.

But little by little I

learned to be flexible.

Mm-hmm.

Talk a little bit about the dance between

stubbornness and flexibility because.

There are nuances there that I

think deserve to be explored.

Mark Uranga: Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: And then I want to,

to talk a little bit about how you've

gotten involved in equine assisted work.

Mark Uranga: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: And then we, I

want to go into a little bit about,

as a pediatrician, what you see as

the value of equine assisted work.

So let's start with that dance

between stubbornness in the

pejorative sense and flexibility.

And then let's go to

mules and equine assisted.

Mark Uranga: Perfect.

Well, I think one of the patterns

that I see in pediatrics and these

interactions, you know, throughout the

day is somewhat of a default coping in,

in all of us at a first level of stress.

Are we, do we cry?

Do we dig in?

Do we, do we freak out?

Do we shut down?

And the idea mule is a great

example of this and not always

because they have the horse as well.

And so sometimes it goes to flight,

but, but a tendency to just stop.

Like, this is not okay, let's stop,

Rupert Isaacson: stop and observe perhaps.

Mark Uranga: Yeah.

And that, that starts, that, that plants

the seed of stubbornness, I suppose.

So if that in a person persists

and we stop and we do not change,

then what is an acceptable coping

strategy becomes a maladaptive

coping strategy, I would suppose.

And the same, you know,

can be true of flexibility.

If, if I change at a whim every, you

know, passing pad, then, then I've

lost a sense of self and where I

might move forward with something.

So the dance, and it's a dance as

I mentioned, I think I see with

every kind of identity or coping

strategy or however a person would

think, is that time where it serves

us well are in, in kind of bulking

as it were, or stopping, am I safe?

Is it safe to continue?

Now I can move on.

That is where I, I think, I

hesitate to think of stubborn

as always maladaptive, right?

And I, and I do, you know, it gets to

the nuance of definition, but I think

that it's fair to call it stubborn

first because I do believe that it's,

that it becomes persistence when it's

adaptive and that it, it becomes a

bad thing when it, when it isn't.

Like you said, you just hold fast

to something that is a lost cause.

That, that's not so good.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

And I think the reason why it was

good to have hear you explore that is

because for a lot of people that are

working with you know, inflexible,

neuropsychiatric, cognitive conditions

you know, I, I had no choice.

I was a dad and I found

myself in that situation.

So I just had to cope and

I had to figure out a way.

So obviously what I did is

I went for mentorship and I

went for mentorship with Dr.

Temple Grandin.

And she said, do these three things.

I did those things and they worked.

So, you know, so my persistence and my

stubbornness is like, I will not give

up on this child in this situation, even

though it's beyond my current resources.

What I'll do is I'll look for someone

who's got those resources and I

will have them, you know, mentor me.

A lot of the people that are working

with special needs, needs, they may not

be coming out of this type of situation.

So let's say you are an 18-year-old

and you are finishing college and you

decide, or, or just you're going out

into the way say, I I like this world.

I, I, I would like to help these people.

I myself am adolescent, which

means I come with a certain

inflexible mindset, you know?

Right.

And because my amygdala is still

not, you know, our, our brains are

developing up until the age of about 25.

I mean, they're always developing,

but you know what I mean?

There's, there's these imbalances

between the amygdala and the, the

hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex

that don't really even out for a

while, which is why, you know, we,

we are rocky and self-absorbed as,

Mark Uranga: as adolescents.

Rupert Isaacson: Right, right.

And we, we come by it, honestly, you know,

it's just how our brains are developing.

And then we kind of cool out a little bit.

But many people are, you know, as

young people are going into the field

before, really their own brains have,

have gone through these changes.

Mm-hmm.

And then horse people, we horse

people and notoriously close-minded.

Mm-hmm.

It's, it's, it's a, it's a drum

that I thump a lot because I, I'm

a great believer that all horse

people should go and learn other

disciplines of hoarseness mm-hmm.

All the time.

Rather than saying, I don't do this, or

I don't use nose bands, or I don't use

bits, or I won't do this, or those cowboys

are terrible, or that hunter jumpers

are terrible or that this is terrible.

That, that's you won't know

until you go and learn it.

If, if you think it's bad,

go learn it and then decide.

I'm often encouraging people in our

trainings to say, if you are asking

Mark Uranga: mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: People who

have difficulty adapting.

To do really difficult things

like communicate or mm-hmm.

With a horse, go into that trailer,

which is a big dark hole, or yeah,

accept a rider on the back, or get toilet

trained if you're a kid or whatever.

Then what difficult, challenging,

Mark Uranga: mm-hmm.

Thing are

Rupert Isaacson: you doing?

What language are you learning?

What difficult physical

skill are you learning?

What computer programming, scratchy,

heady thing are you trying to learn so

that, because if you're not constantly

finding yourself back at the beginner

stage of things, what tools have you

really got to lead somebody else with

two legs or four through that process?

So I like that you are talking

about the need to persist.

Mm-hmm.

How do we cultivate.

Enough open-mindedness so that

we can do what a meal does

so that we can pause mm-hmm.

And observe.

Mm-hmm.

So that, and then go

and discern ah, right.

Okay.

I guess the way down the

mountain is actually there.

Yeah.

Or, yes, it smells of cougar,

but two weeks ago, you know.

Mm-hmm.

Or yeah.

How so?

We don't wanna always override, but

sometimes we need to override, sometimes

we need to say, smells of cougar half an

hour ago, but I gotta get down that slope.

You know?

Yeah.

Alright.

Now how do I, how do I do it?

So that to some degree is

the equine assisted world.

It's, it's, it's, it's dancing.

That dance, um mm-hmm.

How do we, how do we take this

pausing positive stubbornness

Mark Uranga: mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: And turn it

into looking for opportunity for

ways through dilemmas, basically.

Mark Uranga: Well, I, I think

your work does an excellent job of

providing that idea of, I have a goal

of improved communication in mind

with somebody I'm working with with

autism in an equine assisted sense.

And when I see an opening,

that's what I can go with.

When I see a pause, I reflect on

why the pause, why, what caused a

loss of that sense of safety was.

Was it something to validate?

The awareness of that is

critical for moving forward.

That being attuned to that hesitation

is what allows the next step.

So I like

Rupert Isaacson: that being attuned,

being attuned to that hesitation

allows for finding the next step.

Mark Uranga: Yeah, and I love those

times of opportunity with, with

patients, with the, the times that I've

gotten too close to their bubble and

they went from smiling to shut down.

That's in a, in a nutshell, when I'm

building that five minute relationship,

which I get, that's my time to, to rec,

to, to realize that with them, give them

that pause and, and then move forward.

And in a bigger sense,

in a relationship that.

You're developing therapeutically

or we're developing in an equine

assisted sense, those pauses and

that asking of a yes question.

This is a horsemanship, mule manship idea.

Right?

Let's ask a question that

our horse can achieve.

Let's ask a question that our

patient, that our child, that

our colleague can say yes to.

That's what builds the trust and, and that

that connection and attunement, especially

with our non-verbal learners is, is

really validating to their existence.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

So you are, you're a pediatrician.

Mm-hmm.

To you, is the value of equine assisted

work as a whole, why is it a good thing?

I think

Mark Uranga: one of the biggest things it

does is, is it provides a different model.

We're in

a model in science that has a lot of

value for breaking down questions of

is this medicine gonna kill bacteria?

Is this vaccine going to save lives?

But it, but it is not as

good at the holistic pattern.

What combination of things for

a given child create progress?

We, we know that certain models a,

BA for example, and, and something

you're well aware of is one that

shows, shows promise for a number of

people, and we have outliers to that.

Are those.

We know that from the scientific

model, but what we don't always pick

up is the subtleties of the why.

Why is that person an outlier?

Was it you know, time of day person

that we're working with whatever it is.

The, the equine assisted model allows

an entirely different paradigm.

And I think that the work you do

to bring that back to all kinds of

neurotransmitters and the science behind

that validates that the equine assisted

world in, in a scientific model in

some regards, provides the observation.

Science starts with an observation

and a subsequent hypothesis, and

then a testing of the hypothesis.

And then as we is that a, a testing?

Is that.

Repeated testing, do

we get the same result?

And the observation that being

around horses helps me feel better,

helps our autistic son feel better,

allows us to take the next step in

medicine, in the, the research model

of saying, well, is there something

that we can isolate from that?

Is it the horse?

Is it the movement?

Is it the production of oxytocin?

Is it, is it just the handler?

And they could be riding a tricycle.

The medical model, the scientific

model allows us to delve into that.

But there's, there's the mystery

of the horse, the, the of the

horse that is just not easy to

replicate in my experience, I think.

We started with a horse and a, and then

a pony, and then, and then added mules.

And there's just enough more resistance

in a mule to feel a little bit more

like a toddler in that a horse, when

as I worked with them, their pause or

hesitation would tend to be more active.

And in, in my start, I, I felt confident.

Let's say we were trying a new

movement and the, the LOP starts,

well, you wanna elope, let's lop.

I, I love loping.

This is a great excuse for that.

Whereas the mule will tend to have that

pause and forcing through doesn't, doesn't

really get us to the right direction.

It's in, in the horse,

in my horse experience.

I kind of lost that moment.

Why was that?

Because the movement

allowed me to move past it.

Whereas I think that that pause that I

see in a, in a mule more commonly is, is

a little more analogous to a toddler and

and to people, you know, to our peers.

Mm-hmm.

Because there's, there's that not just,

well, I'm gonna flee the scene that's

a little more inherent to the horse.

The, the response of a mule still has

that opening for, okay, now we're both

here not doing what I would like to do.

How do we still get there?

Rupert Isaacson: Interesting.

So it kind of forces more

inventive communication in a way.

And I think we also all know

that mules are hyper intelligent.

They're, they're more intelligent

than the sum of their parts.

Right?

So they tend to be more intelligent

than, horses are more intelligent

than, than ass certainly than my ass.

So yourself, you must

be familiar with that.

With the poet Ogden Nash.

He was a poet American jazz age poet,

writing in sort of sophisticated New York.

And he wrote funny, often satirical

poems about everything from sort of

marriage to making a martini to, and he

had lots and lots of ones about animals

and, you know, the giraffe or the, the

lion or the elephant he won about mules.

And I love it.

It's two lines.

It's in the world of mules.

There are no rules.

Mark Uranga: Perfect.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Yeah.

And to me that Oh, that's funny.

Yeah.

That really is good.

And in, in the in, I've done

two really big mountain trips

in my life using with mules.

One was in Spain 30 plus years

ago, and another one was in Latu in

the highlands of Southern Africa.

And.

What you could really see was the

discernment that the mules had

about how to handle situations.

And that if you were to try

to force anything mm-hmm.

The mule might actually react

badly and push you off the cliff.

But if you when with the mule and

did allow the pause and the slowness

and the, the mule would get you

and your stuff down or up safely.

Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

But you had to meet

them more than halfway.

And I felt that, but it was a fair

exchange by, you know, because

I mean, they're gonna get you.

Yeah.

You are involved in a in an

equine assisted organization.

Tell us about that.

What, where is it?

What is it?

I, I know 'cause I went, you know, to do

a training there, but I'd still like you

to, to introduce it and talk about it.

Yeah.

And what do you feel the value of,

of their particular approach is

that, that, that jives with you?

Mm-hmm.

As a pediatrician, not just

as a dad who wants to do nice

things for, for kids with horses.

So yeah, tell us what is, what is

this, what is the equine assisted

organization that you're involved with?

Just start there.

Mark Uranga: Sure.

The, the organization is called

the Warm Springs Care Farm.

And it's probably the one and the only, if

you were to Google Warm Springs Care Farm,

it pulls its name from the geothermal

hot water that runs down the street,

the warm springs that heat all these

historic homes around along warm springs.

Historically, all those homes

came with enough land for

horses and a carriage house.

And the Warm Springs Care

Farm is one of the few that's

maintained enough acreage to have.

An arena and they've since added

some goats and, and chickens

and these sorts of things.

And the value, I'm lucky enough to

live on the same road and have the same

experience in my backyard, is to come

over a bench and down over a canal into

what feels like an oasis within the city.

And Warm Springs Care

Farm really embraces that.

It's not a forest based

learning environment.

It's it's an, an oasis.

And that comes with small animals as well.

Ducks, chickens, as I mentioned,

goats the, just the break that

adults, you know, we kind of, again.

Circle back a little bit to

the idea that we're, we're all

nonverbal in communication.

These emotions, these senses that

we have, we don't lose them, we

just choose to ignore them at times.

And basically crossing this threshold

at the Worm Springs Care farm, you know,

you're in a place that is a different

pace and the, the role that they play is

creating this space for growth or therapy

that is driven by the participants.

They are not so solely focused

on equine work that they don't

welcome the drumming circle.

They have a, a farm club for kids.

They they have some dance

groups and other things.

They welcomed your clinic, which

was, I think, a breakthrough

for a lot of us in the idea of

how to engage with work that is.

Demanding and compelling yet tiring.

And, and so that organization basically

provides the openness with the physical

location to make those experiences

rich for anybody that visits there.

Rupert Isaacson: You what, what, what

role do you play there and what do you

feel your insight as a pediatrician

brings to you doing that work?

Mark Uranga: Well, I

think it's is such a great

refreshing thing to be able to say,

I know of this place that is magical

that is not another appointment.

It's not another, you know, therapy

that a child is compelled to go to it.

Is something that's engaging and

you know, not all kids are engaged

in that model of growth, but the

ones who are find it so reassuring.

And I think that

with the involvement that that fortunately

I've been able to have some, not as much

as I, as I would like based on demands

of being a working dad and a pediatrician

and a, a mule owner and other things, but

that there's some, some clear validation

to that approach that within medicine

we will have patients that have not done

well in therapy, even though for, for

some people that's the right answer.

Who haven't done well in occupational

therapy building where it's a

more of an artificial environment.

Some kids thrive with what's

provided in that setting.

And the, the role I think

that, that I'm able to play is.

To advocate for the value that they

provide and recognize that as a, a

legitimate and important way forward

for, for families and, and kids, and

that it's not some, you know, hippie

thing that is just, just playing with

animals and, and not growing, but

instead it, it provides that kind of,

that crucible in which growth can occur.

Rupert Isaacson: It's so

interesting that, you know, we

use the word hippie in Peor here.

I say I'm total hippie, obviously.

Yeah.

As a pejorative, because of course the

counterculture otherwise known as the

hippie culture arose out of science.

You know, that the, the, the Allen

Ginsburg and these people who were, they

were all PhDs, they were all doctors.

Most of them were at Ivy League schools.

The, a lot of the people that

engendered the counter culture

movement were actually scientists.

The reason they were, experimenting

with altered states of consciousness

was for the same reason that the

CIA were and still are, you know?

But, you know, with an idea to heal

rather than to harm or control.

And yet we still have this almost

sort of slightly guilty thing of, even

though it was clear, the hippies got

it right in terms of quality of life.

Like what would you have rather

have been in the early 1960s?

Would you rather have been the,

the, the bloke who was just

chain to that corporate ladder?

Or would you rather have been a Woodstock,

you know, I mean, and, and then gone

away and founded Ben and Jerry's?

You know, I mean, which would you

rather, I'm not saying there's anything

wrong with being on the corporate

ladder, and there's also not anything

wrong with being a hippie that does

not go and found Ben and Jerry's.

But many of the hippie generation,

of course, actually did become

really good entrepreneurs as

well as, scientists and so on.

And, and really were the kind of

blaze the trail for the freedom that

we think of now as western culture

that we can clearly see in this world

where it's under threat and Sure.

Challenge.

You know, would we rather live in a,

in a totalitarian society where we

can't express these things or what

would we, well, I think we all know

what we'd rather we'd all, you know,

rather have a bit more rock and roll.

So, and this of course starts with our

children, yet we do still feel this sort

of slight guilty thing about going one.

But I am supposed to be

a very serious person.

And even though none of us ever wanted

to be, because we we're just toddlers at

the end of the day, and you talk about

saying yes, it's good as a doctor to be

able to give validation, you know, we,

we now know the neuroscience behind.

Hippy dom, why it works.

Mm-hmm.

You know, whether it's an altered

sense of consciousness and why they

work or whether it's why working with

horses through oxytocin and BDNF brain

derived neurotrophic factor, which is

actually neuroplasticity, why it works.

These things have now been looked at.

And then you can get to the more

esoteric stuff, you know, like the

HeartMath Institute, you know, looking

at the emission of photons outta

the heart and electromagnetic plus

people say, oh, that's all bollocks.

Well, I live in Germany,

it's not bollocks.

The University of Castle up

the road, which is very German.

Mm-hmm.

Did a whole study about 20, 25 years

ago into the emission of photons

from human hearts and how in states

of empathy, we actually, they go way

farther out and therefore, you know,

we do actually affect the people

around us in this really positive

way and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

So it's well studied.

Right?

It's well studied.

Mm-hmm.

Absolutely.

But, but yet it.

The authoritarian thing because

we all inherited this religious

and militaristic thing.

Mm-hmm.

There's some little part of us

that did drink the Kool-Aid.

Mm-hmm.

And even though it's cultish, it is

frankly cultish feels a set slight

sense of kind of guilt for the fact

that we know that that's the better way.

So I I, I love that as a doctor, you

can, you can then say, well, look.

Yes.

While certain types of very structured

therapies will provide some answers,

there are not just a few outliers,

there are hundreds of thousands of them.

Yeah.

And yeah.

You know, my, my son did not

do well with a, BA, you know.

No.

Right.

Absolutely not.

And, and a BA people they do not

invite Temple Grand into their

conferences because they know

she's going to say, sorry lads,

but it's too limited, you know?

Because at the end of the

day's, coercive, you know, yeah.

But.

You have also talked about I don't

wanna talk about what we're against

because also I know very good a, BA

therapists and in the state of California,

you can actually get Horse Boyer

movement method approved as a BA yeah.

You know, because there are certain BCBAs

down there who believe in what we do.

So I, I don't want to be in

this sort of them and us thing.

But one thing I love that you have said

is that I've written them down, you have

said, as well as stubborn and attunement.

Mark Uranga: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: You said

a place that is magical.

Mm-hmm.

You also said the mystery of the horse.

Mm-hmm.

You also said the of it all.

And yet you're a doctor

where your job is to be the,

not the, you know, not,

not, I've got, I'm sorry.

So magic mystery, being

comfortable saying, I don't know.

Mark Uranga: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: When we go into

a pediatrician's office, that's

not the language that makes people

feel at ease, and yet of course we

know that this is 50% of reality.