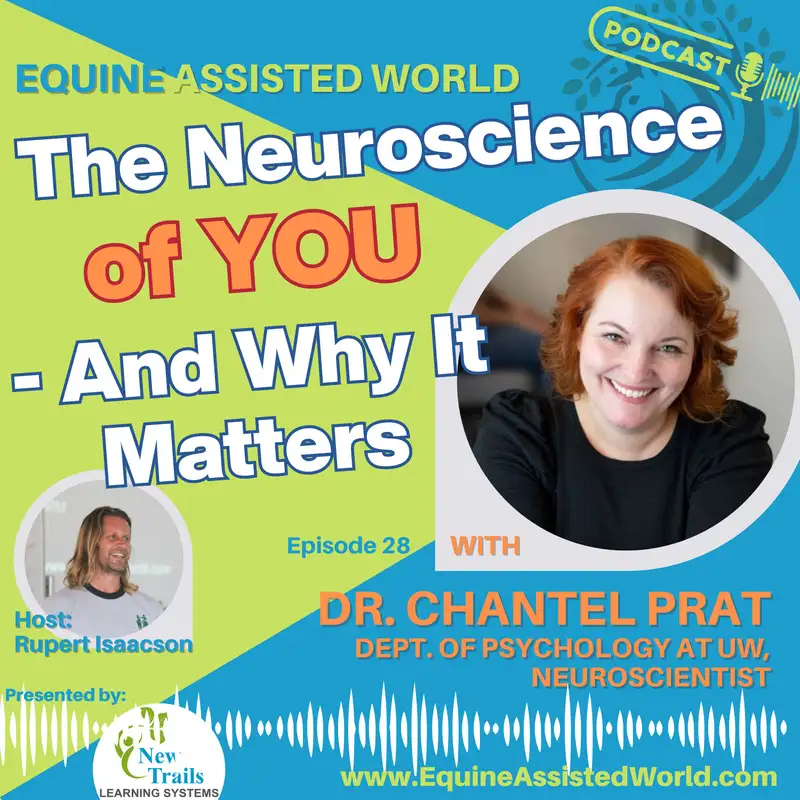

Your Brain, Your Way: Curiosity, Neurodiversity, and Healing with Dr. Chantel Prat | EP 28 Equine Assisted World

Rupert Isaacson: Welcome

to Equine Assisted World.

I'm your host, Rupert Isaacson,

New York Times best selling

author of The Horse Boy, The Long

Ride Home, and The Healing Land.

Before I jump in with today's

guest, I just want to say a huge

thank you to you, our audience,

for helping to make this happen.

I have a request.

If you like what we do, please

like, subscribe, tell a friend.

It really helps us get this work done.

As you might know from my

books, I'm an autism dad.

And over the last 20 years,

we've developed several

equine assisted, neuroscience

backed certification programs.

If you'd like to find out more

about them, go to newtrailslearning.

com.

So without further ado,

let's meet today's guest.

Welcome back.

I'm your host Rupert

Isaacson, and I've got Dr.

Chantel Pratt with me today

who's a neuroscientist.

And as you know, in our work movement

method, horse Boy Method Tacking, we like

neuroscience because we tend to be working

with the brain and the nervous system.

So it's sort of logical for us to look to

neuroscientists who hopefully understand

about such things for mentorship.

So I'm excited to have Chantel on today.

Chantel's also a horse, woman

and has dived into that side

of neuroscience as well.

So we get to ask her some questions

about horses', brains but also about.

The interaction between a human brain

and what goes on with horses, because

those of us who are involved in

the therapeutic and equine assisted

world need to know these things.

And because the science is rapidly

developing all the time and changing,

we sort of rely on people like

Chantel to keep us up to snuff.

So Chantel, welcome.

Thank you for coming on.

Who are you and what do you do?

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Thank you so much for having me.

You might have noticed that I laughed

a little bit when you said Dr.

Chantel Pratt.

It's true.

I am a doctor, but I'm also

a first gen college student.

My husband and I both were

raised by people with high school

educations and I still, I mean,

I think I got my PhD in 2004.

But it's still more often

than not someone's making fun

of me when they call me Dr.

Pratt.

'cause I've just crashed into a.

Hole with an ice cream cone

or something like this.

But nonetheless, yes, it is true.

And and I really deeply believe that

science is an important way for asking

and understanding these big questions

that at the end of the day feel

almost more ethereal or I was going

to say metaphysical, but like when you

were talking about myself as a horse

person and myself as a neuroscientist.

I thought like both of these are really

hard things to understand and I, I

just wanna start by say, I'm gonna

give you my credentials and what have

you, but I just wanna start by saying

that probably because of how long I've

been studying these things, and I'm

talking, looking at pictures of brains,

you know, doing the numbers you know,

working with baby and, and older horses.

And I have a huge amount of humility

and I, and I probably am much more

aware of all of the things I don't

know than the things I do know, because

these are really complicated questions

and really intense, immense goals.

So.

That being said I am a neuroscientist,

a psychologist, and a linguist at the

University of Washington in Seattle.

My research for over 25 years has been

looking at individual differences in

how the brain gives rise to the mind.

So I am a cognitive neuroscientist

by training, which is a fun thing

to say when somebody asks you at the

bar, because they either will leave

you alone, pretend to understand

what it means or ask the question.

But, you know, neuroscience is

a huge field and some people

are really, you know, trying to

understand it at the chemical level.

And some people are very interested

in the nervous system from the

neck down, the, you know, the, the

body and the spine and all of that

important stuff, vagal and et cetera.

And I have really been focused on the

sense-making aspects of the brain and.

Not just the sense-making aspects of the

brain, but how our individual biology

and experiences give rise to the way

that we connect the dots when we try and

understand the world and our place in it.

And this is huge.

You know, we were talking to, I

was, I started by saying I have a

lot of humility about this, but I

just wanna point out that our, our

brain is about 86 billion neurons.

It's one of the most, if not the most

complex systems studied by humans.

It's totally crazy to get into the idea

that your brain is studying itself.

So all of the limits we have in

understanding the thing are, you know,

it, it's, it's a closed loop system here.

But even though the brain is complex

and powerful, it's, it's finite

and it tries to understand and

operate in this infinite world.

This infinite world full of energy

that is constantly changing by

taking discreet bite-sized chunks of

information and then connecting the dots.

We're constantly trying to figure out

what's going on now based on what's

happened to us in the past, and

we're constantly trying to predict

the future, but we really don't

like our understanding of the now.

The past and the future is

just largely inferential.

It's largely connecting the dots

and people see, think, and feel

differently because they have different

brains and different experiences

that have shaped those brains.

Rupert Isaacson: Tell us about your

book and the studies that went into

that book because this is really,

seems to be at the heart of your

work is, is looking at individuality.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: And what that means.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: So yeah,

so tell us about it.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

My book is called The Neuroscience

of You, how Every Brain Is Different

and How to Understand Yours.

And, you know, the book was created

with the goal of helping people

understand themselves first and foremost.

I think you know, I've been arguing that

theories about how the brain gives rise

to the mind that are one size fits all,

which is the vast majority of research

that exists don't fit anyone very well.

It's just like one size

fits all T-shirt, right?

It's down to your knees or, or not.

And and importantly, I think in

that process of helping people

understand themselves, I hope I am

laying a foundation for, for helping

people to relate across differences.

So if we think that

there's one way to learn.

Well, if we think there's one way to

be intelligent, if we think there's one

style of decision making that is good,

we, we operate in this totally false

paradigm that makes us see differences

as better, better or worseness, right?

We, we, we naturally line

up like, oh, I'm smarter.

I'm better at math.

I have a good memory.

I am, and, and the truth is that the

human humans are social primates.

Our brains evolved to solve problems

collectively in groups, in small family

groups mostly, or small tribal groups.

Because of this and because their vast

power and because we can never understand

the infinite ever-changing world, these

differences are features, not bugs.

We, we, there are trade-offs in

the different ways that we can be.

And the book talks about things that

vary from introversion and extroversion

and how that's explained by our

dopamine reward system to whether

we are like strongly right-handed,

strongly left-handed ambidextrous.

And what this says about how jobs get

assigned to our two hemispheres, always

looking at trade-offs, always looking

at the match rather than saying, this

brain design is better or worse, looking

at what is this brain design well.

Well designed to do what is the

match between what I am asking

my brain to do and my natural

predispositions and the things I've

learned from my previous experiences.

So, I mean, I'm, I'm about, when we

get off this podcast, I'm going to

start week 10 of a class that I'm

teaching here at the University of

Washington with 30 undergrads who

have gone through the book, done a lot

of me, what I call me search, right?

Done a lot of tests to figure

out how their brains work.

And probably the thing that I'm

proudest about is to hear people move

from saying things like, I'm bad at

attention, or I'm bad at memory, or I'm.

This way and that way to saying

like, there's a trade off, or I know

that I'm better at this than that.

And just that the sort of self-acceptance

and awareness that comes from

understanding, from moving from a sort

of strength deficit idea towards thinking

about the match between the environment

and what you're asking your brain to do.

Rupert Isaacson: Of course, the

environments that we find ourselves in are

largely determined by economics, right?

Yeah.

And so the diversely,

express,

ishness of the human species,

which I presume must be

across all mammalian species.

Mm-hmm.

Presumably comes about because any

natural environment has an infinitude of.

Potential things that can happen.

Mm-hmm.

And you might be, you might

specialize, so you might be more

hunter or gatherer if you are.

Mm-hmm.

Within hunter gatherer, you

might be more, you might be more

running hunter or bow hunter.

Mm-hmm.

Or tracker.

Mm-hmm.

You might be more medicinal plant person.

You might be more really able to discern

between plants that almost look the same

as each other, doppelganger type plants.

Mm-hmm.

Or you might be the person that

can really get up well in the

trees and shake down the nuts.

So you could see, you could

definitely see why all of these.

This infinitude of brains would evolve.

Mm-hmm.

In any kind of, and I think

Dr. Chantel Prat:

more so, more so in, in

animals that exist in packs.

Right.

So I think that there are revolutionary

so I think that like, you know, I, this

is not a brain thing, but I, I always

compare the human brain to the pea

cocktail where it's like, okay, you can

say this pea cocktail is better or worse

than this peacock tail based on how long

it is or how colorful it is, or, you know.

So I think in like, less collaborative

animals, there probably are things

that are more adaptive than others,

but there are always differences.

Right.

I guess the way selection, selection

has unfolded for humans, you know, we

selected four differences for sure.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

So we also have the ability

to pool our knowledge.

Right.

So

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Correct.

Rupert Isaacson: And make strategies.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: That seems to

be our, our biggest superpower.

We're sort of.

Victims of our own success perhaps.

Yeah.

But you could also see how we've arrived

in the kind of culture that you and I live

in at a point where economically now we've

almost specialized our environment to a

point where only certain types of brain

can thrive in an easy or straightforward

manner, and other types of brain

get undervalued.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: And for real reasons,

because within that more narrow economic

confine, indeed there are only like

these three or four types of brain that,

you know, really do well with that.

And all those other ones,

perhaps not so much.

And this leads us into, or

here's a, is a question.

Does this lead us into a

false set of assumptions?

About normality.

Mm-hmm.

And where we think normality is

being able to conform to that narrow

economic construct, whereas in

fact, that narrow economic construct

itself is, is an abnormality.

Mm-hmm.

In the sort of greater history of mankind.

Mm-hmm.

And therefore, we're actually

mistaken, but we're sort of

right and wrong at the same time.

And then if you come along with someone

like me who would say, well, my experience

of maths at school in the way that I was

taught means that I think I'm bad at math.

Later on when I had to homeschool my

son in math, I realized that being bad

at math was actually kind of a good

thing because it meant, meant I could

empathize with somebody who was No.

And, and I could, I could look at.

How to break things down.

So I had to understand it first, and

if I could understand it with the

difficulties I had, then there was perhaps

a sporting chance that he might Mm.

Or they actually turned out to

be better than me, of course.

But

I guess the question I'm asking is, do

you still feel in this day and age of

the recognition of diversity, which is

different to when we were kids, that the

sort of narrow idea of what's normal and

what's not normal and what's a, a good

brain and what's a bad brain, or has,

has that now not all broken down a bit?

Or am I just living under completely

false solutions because I work within

this field and think that people are

actually, are, are people still stuck

in these ideas of normal and, uh mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

So there's two, two

things I want to address.

The first is about this particular

economic, the definition of good

being based on what makes money

or what functions in the way

we've set up Western societies.

Mm-hmm.

And then you started to

answer the question by talking

about teaching your sons.

I think it starts in education.

I think the big problem is

actually how education is set

up, not how industry is set up.

And I think that our

educational systems are largely.

Set up.

I mean, it just boggles the mind because

education is set up from a time in which

only the teacher had the knowledge and

like, you know, you're supposed to sit

and sit still and listen because you

have to transfer in this laborious way,

knowledge from one brain to another.

And we're so far, we've, we have evolved

as a society, not as a brain, because

where the brain is coming from, written

language is still new and hard, right?

So when you think about chat, GPT and

all this stuff, like we've come so far,

but yet we still have this model in

which kids are supposed to sit still

and passively absorb instruction.

And that is so far from how any brain

evolved to learn and problem solve.

That I think you know, the challenges

when it comes to value and what

we value start much earlier

than, than in the economic cri.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

And you talk, there is a correlation

between that and industry, right.

Because of course, making

kids sit down, shut up and

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yeah.

Behave

Rupert Isaacson: was part of preparing

them to go work in factories,

Dr. Chantel Prat:

sit in front of a Yes.

Sit in front of a computer and,

Rupert Isaacson: yeah.

Yeah.

So I mean, does not one create the other?

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yes, but not necessarily.

I think what, and I think both to

your question about where are we

now, I think both are, coming to

understand and appreciate differences.

Mm-hmm.

For different reasons.

So like I would argue,

and, you know, I do.

So, I am on the advisory board for Ariana

Huffington, who founded the Huffington

Post, has a company called Thrive Global,

and it's about wellness in the workplace.

And we're creating a training there

about diversity in the workplace

and specifically about the benefits

in decision making that come when

you have different brains with

different backgrounds at the table.

So I think I would argue that

there is an economic advantage to

considering many different brain types.

To having people who think, again, as

we evolve to think and make decisions

in groups, to valuing people with these

different brain types at the table.

And when you create work environments

that support different kinds of thinkers

and deciders, and you incorporate

their ideas, you also create products

that work for more kinds of thinkers.

Mm-hmm.

So there, and, and and so I think we are

at a sort of turning point where, you

know, I, I've been spending more and more

time with C-level execs who understand.

That diversity is not only about sitting

around a table with people who look

different than you and think the same.

That's not it.

That's not the magic sauce.

It's sitting around a table with

people with different experiences and

different brain types that they can

bring into this decision making space

and learning how to appreciate these

different perspectives and find something

that will work well for more people.

That there are a lot of

advantages in that space

Rupert Isaacson: is industry

actually now Refinding the

hunter-gatherer model because

industry itself has become so diverse.

You know, it used to be.

Mm-hmm.

A factory was sort of a factory and it ran

with an assembly line and you know, you,

and it's now looking very, very different.

And in a few years, robots

will do all that anyway and.

Are we at the point now this interesting

point where we're returning to a sort

of hunter-gatherer economy, but that's

post-industrial, where we actually

now suddenly realize, oh my gosh,

yes, we do need to create products

for all these different brains, but

this is actually, again, quite new

within the, since the Industrial

revolution, things were more homogenized.

Yeah.

Interesting that, that you're there.

What, what do you say?

You're working with

these CEOs and so forth.

What are they saying about this

and what are they, and then how

are they able to make their work

environments possible for Yeah.

People with these different brains.

That's not just lip service saying,

well, we're gonna hire Right.

So people Right.

Exactly.

Gonna hire so and so.

Exactly.

But they're gonna just go

and shred paper or whatever.

Yeah, exactly.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Exactly.

And so I think that that's,

that's the real work.

So your, your vision of returning

to hunter gatherer is quite

interesting because that's

the work is that, naturally.

I think because of the way that

we understand one another, there's

all this really interesting social

neuroscience work that shows that if

we're in the wild and we're moving

around choosing our friends, we

choose people who work like we do.

Like you can predict.

They did this crazy fascinating study

on an island in South Korea where they

created a social network of like 700

villagers and then stuck them in a scanner

and measured their brain connectivity

and showed that you could predict who

would be friends with whom based on how

similarly their brains were wired, and

that this explained, you know, friendships

above and beyond things like age.

Politics, personality, so long

as they live close enough to

have come into casual contact.

When we're choosing people to spend time

with, we choose people who work like us.

And I think that's because our sort of

default to mirror neurons and so forth

and so on, allows us to make easier

intuitive inferences when somebody

works like us now in the workplace.

I think that often how this

translates is when they say somebody

is not a good fit culturally.

Like there are all these kind of like code

words when you're in hiring and you might

say it's not a good fit for the culture

or, and I think that that's a feeling that

comes when the person you're interviewing

has a different brain, a different

thinking, feeling, behaving style.

And I also think that we are more likely

to think someone who comes up with

the same solution as we do is smarter.

Because you can understand that solution.

You agree with it.

And so you're like, oh yeah, this

is a great person I have on my team.

It's like duplicating Triplicating

myself, cloning myself.

And so people need concrete

examples and evidence.

It's hard.

It's certainly harder to create

communication styles to create

management systems that go away from

assumptions about how people think,

feel, and operate towards, you know,

more personalized, individualized

spaces that support these differences.

And they need concrete examples for how

this is gonna make them money, right?

And how the decision making will look.

'cause it's not gonna feel.

Like, oh, this is great.

You're brilliant.

I love you.

It's gonna feel weird.

Like, and so that's where I think

the, my book has helped give some

kind of engineering examples.

Like, this is how brains work.

These are the weaknesses that are

associated with all these kind of fast,

instant, probabilistic decision making.

This is what you're missing.

And so getting people to feel

curious about the brain across

the table that is saying something

that you might think is asinine

or doing something that

you might think is asinine.

That's, I think, the magic and the secret

sauce, because every brain does things

that they think are perfectly reasonable.

Every brain, every single brain

is moving through the world trying

to find good things and avoid

bad things based on their, their

engineering and their experiences.

So instead of thinking, why is this

idea asinine, asking questions about

how that person got to that place.

Is this kind of opening

experience for sort of,

you know, sort of reconceptualizing

better or worse, right or

wrong with what am I missing?

Yeah.

What is this person

highlighting that I missed?

Rupert Isaacson: I just wrote down,

I just wrote curiosity underlined.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yes.

It's curiosity is the magic.

It's my favorite thing that I

learned about in writing my book.

And it's the secret sauce I think.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah, I agree.

And I, you know, without

curiosity, there's no innovation.

Without innovation, there's no

long-term thriving economically.

Right.

Because conditions change.

So one has to, whether it's in hunter

gatherer context here, there could be

a drought, there could be some natural

thing that causes the shifting of changes.

Mm-hmm.

Natural resources.

Mm-hmm.

Obviously market forces, you

know, we're seeing some disruptive

market forces going on as we as,

as we speak here in March, 2025.

It's an interesting time.

Oh, boy.

If you're not curious, I mean, yeah.

How can you, how can you

thrive in these things?

Right.

I want to bring you back though,

to, you talked about mirror neurons.

Mm-hmm.

Mirror neurons are something which

you hear a lot of people talk about.

Mm-hmm.

But I've got a, I've just caught a

neuroscientist on the end of my screen.

Tell us exactly what neuro,

what, what mirror neurons are.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Well, I can tell you exactly how they

were discovered and then I can tell

you about the ambiguities of them.

Right.

So a mirror neuron.

At its core is a neuron in the

brain that responds, that is both

involved in generating an action in

the person themselves and when they

observe someone else doing an action.

So it was first discovered in

Italy in a monkey lab where they

were actually trying, so they had

electrodes in this monkey's brain

and they were doing they were, you

know, I don't know, putting fruit.

On a tray in front of the monkey.

And what they wanted to see is

like what part of the motor cortex

executes a specific grabbing response.

So there's a lot of motor pro, a lot

of brain is involved in just motor

programming and what they found, so

they had, you know, these motor cortex

neurons isolated for this monkey's hand.

And what they found was the experimenter

who was a human, by the way.

Obviously, I guess, I

mean, would be really cool.

I

Rupert Isaacson: should be surprised.

I mean, it

Dr. Chantel Prat:

would be really cool to have monkeys.

But anyway, it was a human, that

Italian monkeys, no, that exactly.

They're very social and very, very smart.

But the, when the human put like

the, you know, the fruit, the treat

on the tray, they used the same

grasp, the same motion that they

were trying to study in the monkey.

And they found these neurons started

firing these neurons that were supposed

to be for motor programming started

firing when they saw someone else.

Do the action that they

are supposed to do.

So we know that there are populations

of neurons in the human brain that

are both involved in the per, it's

really important for language.

For instance, there are neurons in,

around, in and around the sort of speech

bro's area that will listen to speech

sounds and they sort of activate the

motor plan that would create those

speech sounds and that helps them

understand where, where are the brain?

Are

Rupert Isaacson: these located

Dr. Chantel Prat:

mostly in the frontal cortex?

So they're mostly in the, I would

say, both sides of the frontal cortex.

Now what happens is, I think so, so

the criteria for something to be a

mirror neuron specifically is that

I both generate a behavior and.

I respond when I see other

people doing that behavior.

Okay.

And, and that's, and so like, you know,

in the original research on animals,

we had an you know, an electrode

in the brain and we were really

specific about what was going on.

Now there's, I think that the research

has gotten fuzzier because when

you're looking at human brains and

you don't have electrodes in them,

there are a lot of parts of the brain

that do a lot of different things.

And so, you know, the mirror I, to

the best of my knowledge, mirror

re neuron research has become

controversial in some areas.

So like, one of the things that I think

is quite evocative is the idea that mirror

neurons are involved in empathy and and.

One of the reasons I think this

is evocative is how hard it is to

just, is empathy a single thing?

How hard it is to define empathy, how hard

it is to catch a brain being empathetic.

And so usually when they study, you

know, you have to think about this.

If you're thinking about flow or like

creativity or things that are really

cool that we actually wanna understand.

If we can't time it to the precise

millisecond, if we can't catch it

in action, if we can't cause it, how

sure can we be that we're studying it?

So with with empathy, often what

they do is watch somebody get hurt.

It's like a physical pain, empathy,

and it, and then you're looking at

like, activation in the sort of somatic

somatosensory areas and you know.

Similar.

Like you see somebody get hit

with a ball or something and you

look for like the feeling of pain.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: They get hit in the army.

Clutch your arm, right?

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yeah.

Right.

And you I do, I definitely feel, yeah.

You know, that's why I, like, we have,

I, I probably shouldn't talk about this,

but like we have a divide in my family

about nut shot videos and whether or not

they're hysterical, I like feel it, I

don't, obviously don't have testicles,

but like I feel the pain from those so

viscerally that I can't, they're both

Rupert Isaacson: painful and funny.

I'd say that they're both right.

But my husband

Dr. Chantel Prat:

and my daughter think they're

hysterical and will cry and just

watch like endless snapshot videos.

So I'm like, okay, is that something

different about our mirror neurons?

Like, I don't know.

It certainly crosses gender.

So, I don't know what's going

on there, but, but that's a very

specific kind of empathy, right?

So I, you know, to the extent that

that generalizes to cognitive pain, you

know, to emotional pain I don't know.

But, but the, you know, when it comes to.

How we understand one another

and how we understand our horses.

I think this is fascinating 'cause

the, you know, the idea is that

mirror neurons is kind of a way of

understanding through simulation, right?

Like, I watch you do an action, the part

of my brain that would execute that action

activates and I think ow or whatever, you

know, but I think this is why we're drawn

to brains that work like ours in the wild.

'cause this isn't mirror neurons

are intuitive, instinctual.

It's, it's not learned.

It's why little kids cover their

eyes and think they disappear.

You know?

This is our, the easiest way of

understanding one another, I think.

And so.

If you and I have totally different

wirings and I'm watching you behave,

and I'm simulating it, and I'm thinking,

this is asinine, my brain is different.

So when my brain walks through, thumbs

up, when my brain walks through, what

it would be doing in that case, and I

have all these different priors and I

have all these different wirings, and

I think that makes no sense whatsoever.

Then it's like stepping into

shoes that are a different, you

know, walking a mile in someone's

shoes that are a different size.

So that's where I think the, the more,

what Paul Bloom, I think, wrote a book

called Against Empathy, a, a Case for

Rational Compassion, where he talks

about understanding in this more what we

call theory of mind way, which is a more

abstract clue based use the information

to reverse engineer somebody else.

And I think that kind of theory of

mind understanding is not as warm,

it's not as a effective effective,

but it allows you, I think to

understand people who work differently.

Than you do, like you might and,

and with the horses, I think it's

interesting to, to consider how

much we're feeling with a horse and

getting it wrong because the horse

has a different experience than we do.

Yeah.

Versus using the bits and of,

you know, the bits we've learned

about how horses work to kind of

rationalize what might be going

Rupert Isaacson: on just

quickly, just to beat the, the

dead horse on mirror neurons.

Mm-hmm.

I, am I correct in, in thinking that

a mirror neuron is not just a mirror

neuron that a mirror neuron does?

Lots of, might do other things, might

have other jobs it does as well.

Of which the imitation

Dr. Chantel Prat:

right

Rupert Isaacson: thing, it's

just one function, but they could

equally do other things as well?

Or is it dedicated?

Dr. Chantel Prat:

I don't know the answer to that.

So I think that I mean they

have at least two jobs.

One would be executing

the behavior in you.

Mm-hmm.

Like you don't only, so I guess maybe

that answers your question, that

part of the brain in the monkeys

is firing when they're trying to

grab a, a, a grape, whether they're

seeing someone else do it or not.

So it is involved in social imitation

and learning, but it has a, a

primary job in controlling your body.

Rupert Isaacson: So if we're involved in

the sort of therapeutic writing end of

things, which obviously a lot of people

listening to this show are what I presume

that trying to optimize people's mirror

neuron development would be a useful

thing because it helps them to learn how

to thrive in a confusing world by kind

of learning which behaviors to emulate.

Mm-hmm.

What's the best.

Advice that you would give to somebody

working in Sayan equine assisted

field who wanted to help somebody

optimize their mirror neurons?

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Do optimize them for other people or,

Rupert Isaacson: well, for both.

I mean, 'cause I should imagine cross

species, if you are, if you talk

to a lot of autistic people, for

example, they'll say, well, it does

feel like I'm dealing with another

species when I'm dealing with you.

Mm-hmm.

So whether I'm dealing with a

horse or whether I'm dealing with a

neurotypical human, whatever that is.

And then similarly for neurotypical

humans, when they're dealing with

people on the spectrum, it can

feel like dealing with, it can feel

like dealing with another species.

And this is where the

communication breaks down.

So how can we help ourselves

out neurologically Yeah.

As the practitioners so that we can help

our, our, if you like, service users.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Mm-hmm.

So my instinctive response is that.

To the best of my knowledge, and I will

admit that I'm not an expert in this,

the mirror neuron system is pretty

I'm so hesitant to use the word innate,

but I guess what I would say is I would

sca rather than trying to train the

mirror neuron system per se, I would

be trying to train explicit behaviors.

Like if the mirror neuron system is

working atypically, because this is

something you see in, in infants.

You see them imitating facial expressions.

You, this is something

that's been milestones,

Rupert Isaacson: et cetera.

Those milestones are not happening, right?

Yeah.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Right, right, right.

So, I mean, it, it, it's either been

unfolding or not unfolding typically

up until the point of intervention.

So, you know, my, what I would be

doing is making the things that

might be implicit to us explicit.

To the learner.

I think that that's a more

tractable learning technique.

Right.

Put that in

Rupert Isaacson: terms that somebody

walking around an arena with a

kid on a pony in Staffordshire

Dr. Chantel Prat:

mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: On a Tuesday night.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

So you want them stand and

Rupert Isaacson: put into practice.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

So again, is, are we trying

to get them to understand the

pony or the, the instructor?

Rupert Isaacson: That's a good question.

If you're in the equine assisted

field, or if you're considering

a career in the equine assisted

field, you might want to consider

taking one of our three neuroscience

backed equine assisted programs.

Horseboy method, now established

for 20 years, is the original

Equine assisted program specifically

designed for autism, mentored by and

developed in conjunction with Dr.

Temple Grandin and many

other neuroscientists.

We work in the saddle

with younger children.

Helping them create oxytocin in their

bodies and neuroplasticity in the brain.

It works incredibly well.

It's now in about 40 countries.

Check it out.

If you're working without horses,

you might want to look at movement

method, which gets a very, very

similar effect, but can also be

applied in schools, in homes.

If you're working with families, you can

give them really tangible exercises to do

at home that will create neuroplasticity.

when they're not with you.

Finally, we have taquine

equine integration.

If you know anything about our

programs, you know that we need a

really high standard of horsemanship

in order to create the oxytocin

in the body of the person that

we're working with, child or adult.

So, this means we need to train

a horse in collection, but this

also has a really beneficial

effect on the horse's well being.

And it also ends your time conflict,

where you're wondering, oh my gosh, how

am I going to condition my horses and

maintain them and give them what they

need, as well as Serving my clients.

Takine equine integration aimed

at a more adult client base

absolutely gives you this.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Because for the pony, like I would say,

do you notice what his ears are doing?

Like, what do you think that means?

You know, and how about how does that

look compared to this Pony's ears?

Like, you know, what

can we learn from this?

And like with the instructor or with, you

know, Billy, you could say like, you know.

When you said, Hey, shut up, or

whatever just happened, like,

you know, what did you notice?

You know, you know, did you see this

thing and you can like point out and now

Rupert Isaacson: what if, what if the per,

that all sounds highly reasonable, and now

what if the person doesn't have the kind

of brain that can receive information in

that way, sort of top down instruction.

Mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

So what if they're, what if they're

like severely autistic or mm-hmm.

Away with the fairies in whatever way,

and you want to help to bring them into

this type of empathetic cognition.

Mm.

So that, not so that they can be

changed, but just so that they

don't get their ass kicked mm-hmm.

Too heavily by the world that they're in.

How could we, what, what, what are some

things that spring to mind for you?

Dr. Chantel Prat:

So the thing that, to help kickstart that

Rupert Isaacson: process,

theory of mind effectively.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yeah.

The thing that makes sense to me,

based on my understanding of the

brains of people with autism is that

you've got a, the thing that you want

them to learn about, you've gotta

restrict distracting information.

So you would need to simplify

the world to the extent that

you could make the learning item

of interest the most salient.

So I hear you saying like, I'm on a

horse and I, and my brain is not verbal,

or it's not programmable in this way.

And part of that is because you're

the, you know, the things that they pay

attention to are not as predictable as

the things that we pay attention to.

Like, you can you in a neurotypical,

individual, you can, there are

certain things like social cues,

like language, like faces that take

priority a lot of times over things

that would be very salient for someone

with autism, like repeated motion.

Of course.

That's, you know, that's what we're

working toward by, or like, machines,

anything that's predictable is something

that might help attract their attention,

which is kind of the exact opposite of the

noisy, chaotic human face and, and voice.

So I guess, and I'm sure people have

done this because it seems obvious the,

the learning should be happening

in a situation that is as free

from other kinds of distraction

as possible to make the, the.

The cue, you know, so when I think of

mirror neurons, I think of a match between

what you're seeing and what you're doing.

And to the extent that such a thing

could be trained you would want

to just eliminate every, every

other kind of as many other kinds

of distracting things as possible.

So I, I've, I've read about, for instance

vocabulary development in autism.

And it's fascinating because, you know, in

a typically developing brain, mom can take

a pen and go point to it and say, pen.

And there are all these, you're

listening to mom's face, voice the point.

There are all these social

cues that point you to this.

The attention on this object

and, and a typically developing

kid with autism is like.

Listening to the finger, the butt,

the way the socks feel, and the shoes,

like you might learn any amount of this

sensory information might be capturing.

Right.

Your attention.

Rupert Isaacson: You know, it, it,

it's really interesting when I was

first having to get involved in this

'cause I had to 'cause of my son.

There was,

and there still is a belief

among some people that say

a wall with art on it or something

like that would be too distracting.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Mm.

Rupert Isaacson: And then, and so

people would be working in these

really very sterile environments.

Mm-hmm.

White walls, frankly depressing.

Aesthetically.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yeah.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: But I found of

course, going out into nature.

With my

Dr. Chantel Prat:

kid.

Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: Opened everything up.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yes.

And that makes,

Rupert Isaacson: and there were multiple

distractions, but those distractions

seemed to work for us, not against us.

Mm-hmm.

So my question with that is,

Dr. Chantel Prat:

oh, this is a good, this

gives me a good idea.

Okay.

Keep going.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Is, is this is this because a,

those distractions didn't have a

bad sensory effect because mm-hmm.

They're the distractions that

our organism is set up for.

Mm-hmm.

I mm-hmm.

You know, the wind, the, the

light, the trees or whatever.

Mm-hmm.

So therefore they're

not really distractions.

Mm-hmm.

They're just sort of our habitat.

Mm-hmm.

And then do our brains that

automatically respond better to those.

And then the other thing was, of

course, it was all in, in movement.

And that brings me back to mm-hmm.

What you were saying earlier about

with factories and, and schools.

The brain didn't evolve.

To learn and problem solve

that way sitting still.

So I wanted, so I made a

little note to myself, say, ask

about movement and the brain.

So nature movement.

Okay.

And then what I would do, of

course was look for what seemed

to motivate him from the, that's

Dr. Chantel Prat:

exactly what I wrote, I wrote,

Rupert Isaacson: and then

just go in that direction.

That's exactly right.

And the reason I did it though, mm-hmm.

Was not because I was intelligent.

The only reason I did it was because

I'm not intelligent and because I know

that I'm not intelligent in that way.

I went for mentorship from Temple

Grandin who told me to do that mm-hmm.

As an autistic person.

Mm-hmm.

So I, as a journalist went, well, she's

autistic and she's successful, so she

must know what she's talking about.

So therefore I will do what she says

because that just seems rational.

And I did and it worked.

Mm-hmm.

But I, yeah, I definitely found

that following what other, what

sometimes behavioral therapists

would've called distractions, I

found were not distractions at all.

Mm-hmm.

They were motivators.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

That's right.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

That's right.

So, so what's going on

with there, with the brain?

And

Dr. Chantel Prat:

so there's some, my gosh, like there

is a person here at UW called, his

name is Gregory Bratman, and there's a

team that are studying nature wellness

interactions and in so many different

ways sort of nature and mental health.

And like the first thing that I

thought about when you were talking

about walls with no art and versus

nature is this idea of soft.

One of the things that seems to be

true is that when we are in nature,

we are inherently softer in our focus.

We are more like the horses, right?

Mm-hmm.

Like we have this wide picture, and

I do think that that's very settling.

It's restorative.

Mm, for the nervous system, right?

Because we also have something

called like attentional fatigue.

And I think, you know, as you were

talking about the white walls and, and

things like this, I thought, okay, what

is, how do you get from distracting

to like stressful amount of pressure

in one area, which will then fatigue

your brain and your nervous system?

And I think this kind of soft

focus which you also get, we know

this is true from moving, right?

You, the rhythm, rhythm of walking

relaxes the nervous system and it opens

up creativity and opens up like the

ability to think and reason and learn.

So that's the first thing is that

this is, is that the, the way we

focus in nature, we need to be aware,

we need to be alert, we need to know

where we're putting our feet, which

is kind of cool and interesting.

But the, we're not necessarily

hyper-focused on something

that will fatigue the brain.

We have a, a, a kind of broader

awareness, which seems to be from

a mental health point, restorative.

And you're right, that's,

that's how we are meant.

We, we are animals.

And that is how we are meant to exist.

It is, and I think it's in this space of

normal value what's good and what's bad.

I, I worry so much about how removed

we are from how, how many things

that we think are bad about our

brains that are just absolutely the

way that we are designed to exist.

Our brains have not.

Evolved nearly as fast as our society.

The pressures that our

society has put on them have

Rupert Isaacson: what?

What do we think is bad about our brains

that, that we could be wrong about?

I think

Dr. Chantel Prat:

a attention is the biggest thing.

Like, you know, my students like, and I

think that this is a great, I also wanna

talk about your, your question about do we

think we've diversity is accepted or not?

I think it depends.

Attention is a huge thing.

Like many, many people, like you're,

you are saying I'm not intelligent, but

I think that's because you have a very

specific idea of intelligence that's like

sitting in front of books like I am right

now and digesting things and, you know,

and remembering them when they have like,

no tangible purpose in your real life.

Or like, you know, how, how well did you

absorb numbers on the chalkboard when

someone gave it to you without a context?

And, and when it comes to, I just think

that there's a very straightforward way

that your brain defines intelligence.

Your brain defines intelligence

as learning the things that will

move you through the world and

help you find good things, period.

Right.

And so having the ability to like

undergo six hours of class a day

for 25 years of your life before you

finally get a job where you make money

and can then buy the good things is

like not, that's not very natural.

That's a lot of delayed gratification.

Right.

So, I'm completely, I'm, I

am, I'm thinking about nature.

What, what did you ask me?

What's it, the brain, well, well,

Rupert Isaacson: that you

talked about attention.

So, yeah.

Attention.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

So a lot of people feel they hate, like

I I, at the beginning of this class, I

would hear my students saying, I hate.

A DHD.

Do you know how many of my, like in

my students, I'm at the University of

Washington, it's widely considered one of

the 10 bus public schools in the world.

Mm-hmm.

I think that could be changing,

but and so these students are at

the top of what society would call

high functioning intellectual.

And I probably have about 25% of

the students in my class, this

upper division, like neuroscience

class with diagnoses of A DHD.

And I think there's

something in that, right?

So either we can say, and, and if

you look at incidents of A DHD,

it really depends on the country.

It depends on the time period.

It, it could be something

that's increasing because of,

you know, digital stimulation.

It could be something that's di being more

widely diagnosed because of awareness.

But the fact is that one in four.

Students have this diagnosis means

that it's not rare, it's not atypical,

and it also means it can't be bad

Rupert Isaacson: of a thing.

Right.

Otherwise it can't that, that

bad of a thing getting into

University of Washington.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Exactly.

Exactly.

And in some ways but, but, but the

students will say, I hate that.

And then I say, okay, well

let's talk about the opposite.

Do they say why

Rupert Isaacson: they hate it, by the way?

Dr. Chantel Prat:

I think they hate, well, they, they

will say like, I don't know why I

can't be motivated to sit and do

something for a long period of time.

Okay.

Or how, or or that I then get hyper.

You know, they're aware that they

also get hyper-focused and like

down a rabbit hole for something

that they say like wasn't important.

And so one of the things that we've

learned in my class is like, when

you are, you know, what widely.

In both this kind of economical world and

in the classroom, what's widely considered

valuable or good is the ability to pay

attention according to some goal, right?

Like I am, I'm telling you, pay

attention to what I'm saying.

'cause we're on a podcast right now

and that means whatever, or you know,

I'm telling you, pay attention to your

homework or I'm telling you, pay attention

to dropping your heels or whatever, right?

And the ability to, but like.

When people are paying, paying attention

first, it's expensive for everyone.

That's why it's called

freaking paying attention.

It uses the frontal globes.

When you're paying attention, what

you're actually doing is you are

overriding everything you've learned

from trial and error experience.

Oh, that's interesting.

Okay.

So like everything you've

learned about how to stay alive,

how to find the good things.

Mm-hmm.

You can override that to now focus

on a specific piece of the world

and ignore the other pieces of the

Rupert Isaacson: world.

Mm-hmm.

For a specific outcome.

Right.

For

Dr. Chantel Prat:

a specific outcome.

It, it costs a lot from an energetic

perspective and you are literally

distorting the world as it is,

and you are less likely to see

something that you're not expecting.

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

So, you know, if you don't have someone

with a DHD in your, a hunter gatherer

group and you happen upon a cave with

eyeballs popping out of it, you're dead.

Yeah.

You're over here counting blueberries

like you're supposed to and see how

many are in the basket or whatever, and.

You're not even seeing

the eyeballs in that cave.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah, no, absolutely.

And that, that's always been my

thought about a DHD is that, you

know, having, having lived with hunter

gatherers you can see how the human

brain has to be able to operate in

effectively multiple parallel universes.

Correct.

And at the same time hyperfocus.

Mm-hmm.

And at the same time allow

itself to be distracted.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

And isn't it convenient if you

have different people who are

good at those things and can

communicate with one another?

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

Right.

So you can defer to, you are better

at the blueberries than I am.

So when it comes to blueberries,

I'm deferring to Chantal.

So then maybe I can give Chantal the

chance to go down the blueberry rabbit

hole because we'll benefit from that.

And I'll watch out for bears.

While she's doing that because she

knows more about blueberries than I do.

When it comes time to do the thing

that I'm good at, she'll do the

same, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

But, and then, you know, the, the

need to change on a dime and pivot.

Mm-hmm.

So if you're hunting conditions change

like that, the wind changes or the animal

hunts you back, or you realize mm-hmm.

Another animal was hunting you while

you're hunting or whatever it is.

And so if you can't then pivot very,

very fast, well you can't get food.

So, you, one I've often wondered

when people talked about A DHD,

like, is, does a DHD, why is

there a deal on the end of it?

Why is it a disorder and a deficit?

Mm-hmm.

So it's only a disorder and a

deficit, presumably if it no

longer fits the economic model.

So That's right.

Yeah.

And in

Dr. Chantel Prat:

fact, the diagnostic criteria, I talk

about this from time to time because

I study attention and attentional

differences in the lab, and there are

a number of tests you can do about

distractibility focus goal, you know,

orienting all the, you can break it

into a million different boring tasks.

There's no criteria.

There's no, if you get

this score, you have a DHD.

It is not, that's not

how you get diagnosed.

You get diagnosed

Rupert Isaacson: objective.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

It's if you, yeah.

Is this, is this impairing your

ability at home work or whatever.

Right.

In context.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

So that's about functionality.

It's not about typicality.

Rupert Isaacson: Well, right.

And then that depends on what's

being valued at home, presumably.

Correct.

So if, if the home culture is

that, I as an 8-year-old boy should

Dr. Chantel Prat:

sit, still

Rupert Isaacson: behave

like a Philadelphia lawyer.

Yes.

You know.

There might be a small percentage

of boys that can do that at eight.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: But if

you're not one of them,

Dr. Chantel Prat:

then you start to feel like there's

something wrong with a dysfunction.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Then it means that we've

gotten very narrow in

Dr. Chantel Prat:

mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: What we perceive as

an economically viable thing, right?

Yes.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Instead of, yeah.

So diversity, you talk about diversity

and one and one, one thinks about

it as diversity of people, diversity

of brain types, but there's also

diversity of economics, right?

Surely Yes.

You know, we need multiple skill

sets, people with multiple correct.

Skill sets.

Yeah.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

And, and, and Temple Grandin

is big about she is so, you

know, tuned into that as well.

And like, we're under training for really

important skill sets when we had dinner.

Two weeks ago she said that her new

passion is going around looking at

all the certificates everywhere in

the world that have not been checked,

like the elevator certificates.

Yes, she does.

And I was like, I don't like

elevators to start with.

You're not helping me at all.

She's like, they're everywhere like you.

She came, she

Rupert Isaacson: came and spoke at the

conference that we did in September, and

she, the first thing out of her mouth when

she got on the floor, she says, I just

checked the elevator coming up here and

it's out of date by, and we're like, okay.

All using the stairs.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yeah.

Yeah.

Comforting.

Comforting.

But hey, awareness is, is key

Rupert Isaacson: indeed.

What part of the brain, just quickly

about attention, what part or parts

of the brain govern attention?

Hmm.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

So I would say the attention is a, an

interaction between the frontal lo?

Well, it depends on the kind, right?

So there's natural, or I

call it organic attention.

Some people call it distractible.

But I love it because squirrel

is, you know, that's the kind

of prototypical distractibility.

But hey man, squirrel

is an organic attention.

That's thing.

Well, squirrel is

Rupert Isaacson: also edible.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yeah, right.

I mean, why wouldn't, I mean, you

know, that's why wouldn't I look at

Rupert Isaacson: sport?

I might be able to eat it in

a hunter gatherer context.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yeah.

Or you might be able to

make friends with it here.

Theyre, or maybe it's

going quite aggressive.

Steelers of lunches might

be your competition.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

So there's two things.

One is that you have a frontal

lobe that holds the goal in

mind if you're paying attention.

And two is that you have these basal

ganglia, which are my favorite parts

of the brain, which are the the

dopamine rich reward centers that

learn based on previous experiences,

where to find the good things.

Now, the basal gang, my husband has a,

a, a really cool computational model

about this called conditional signal

routing, which by the way, we found was

working quite differently in autism.

And the idea is that when you have a

goal, the frontal lobe can help change

the rules for what good looks like, right?

So like if you know, you know, ice cream

is good and so, and you feel hungry

and there's ice cream, you're like,

this is a high probability reward.

But if you're like.

Energized enough to hold in mind that

you wanna live to be 100 and that

you haven't eaten any vegetables.

The frontal lobe can tell the basal

ganglia, Hey, like right now, actually

fiber, things that grew from the

planet are good in a, like, in a

way that aligns with these goals.

And you can, and you can

make a different decision.

Rupert Isaacson: So it's, so is your

basal ganglia, your impulse and your

prefrontal cortex, what you're talking

about there, that that could override that

impulse for kinda to change what's good?

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Mm-hmm.

Kind of.

I think that basal ganglia are

a lot smarter than just impulse.

I think they're at any, given the

frontal lobe gets all of this, I think

of the frontal lobe, like the CEO that

gets all of this credit for making

decisions, but the basal ganglia are

already filtering behind the scenes

based on your previous experiences to say

this information is pretty particularly

important for making your decision.

Rupert Isaacson: Where are they located?

The basal ganglia right

Dr. Chantel Prat:

in the middle of the brain.

Rupert Isaacson: Why

are they called ganglia?

Right.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

I don't know.

I think that means multiple.

They, yes.

I think I would imagine them like,

Rupert Isaacson: like octopus alien,

Dr. Chantel Prat:

we had a, we had Halloween costume

Rupert Isaacson: type.

Yeah.

With Dangly

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Dang things.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

We had a Halloween costume collective.

We were called the Basil Gang.

I think it means multiple ganglion.

I think it's a thing, but

I don't honestly know.

And then there's this, so it seems

also within this frontal and then

in inner basal ganglia system,

there's also a left and right.

Ideas, and I think this

is super interesting.

The left seems to be more goal focused

and predicting the future, whereas

the right seems to be more focused on

the now and noticing abnormalities or

things that move and so forth and so on.

So, for instance, there's a, a

disorder called the visual neglect

or hemis hemifield neglect.

If you get damage in the in the right

hemisphere, the left hemisphere can still

kind of like figure out what's going on.

But if you miss the noticing

hemisphere, you might just like

ignore an entire half of your body.

So there's this different kinds of

awareness in the two hemispheres,

which is quite interesting.

And if you have people bisect a line, so

we did this in my class, just give a, give

people a bunch of lines and have 'em draw

a a line where you think the middle is.

You can get and, and then measure

how close you are to center.

You can get some idea of whether you

have this more or you know, if your

right hemisphere, if your right, if

the line is to the left of center,

it means that your left hemisphere

is driving your noticing more.

And if the line is to the right,

you can, you can say that you

have like a more organic brain.

So a DHD people are more, are

more driven by the right side.

Okay.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

And we live in a bit of a left

brain society, so therefore Yeah.

Therefore they've, it's

a disorder suddenly.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Right.

Whereas, but it,

Rupert Isaacson: in another culture

it would be a, a a, an asset.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Right.

Exactly.

And I think that that applies to a lot

of different skill sets and a lot of

different ways of being that we're,

you know, sort of under appreciating.

And you know, going back

to your question about I.

The first question, which I feel like I

never fully answered about, are we, where

are we at in the acceptance of diversity?

I love that neurodiversity is searched

for four times more frequently on

Google now than five years ago.

I, I think that there is a general

awareness that probably one in

five people have some kind of,

what, what will be diagnosable

as atypical brain organization.

And I love, you know, these stickers

that say neuros spicy and this kind

of acknowledgement that I think that

there is a general increase of awareness

and a general increase in people

claiming that they're neurodiverse,

you know, like making it public.

Having the neuro spicy sticker.

And understanding that this is not

a personality deficit, this is just

the way my brain works, is kind of a

claiming, stepping into that recognition.

However, I think there's work to do,

number one, I think that, that, that

understanding that this is not like

a personal weakness or a deficit,

this is just the way my brain works.

I think that there's room for that in the

typically developing population as well.

I think, like I said with my

students, people who hate, don't

understand why they're distractible,

don't understand why they're not

motivated to do boring things, don't

understand why they forget forgetting.

This is important for

learning as remembering.

Like I just think there are a lot

of things about our brain designs

that we really, that we perceive

as character flaws because of

this kind of societal value of a

particular thing that's very abnormal.

And I think there are certain.

Labels that are more popular than others,

like a DHD is so metal and rock and roll

and yeah, I'm neuros spicy, but like

when I talk to people who are on, who

have autism spectrum disorder, many of

them don't wanna be the person on that

panel or don't want their employers

to know about it and are worried about

being stigmatized and are worried, you

know, so like, it, it's, I don't think

we're there yet when there's like a

cool disorder and a not cool disorder.

And, and again, I think that nor

I just think the work comes to

it with normalizing differences.

We're all different and people with.

Asper or an autism spectrum disorder

label are just as different from

one another as people without it.

Like, you know, so assuming that

that per that label lets, you know,

oh, I'm gonna, I don't know, like

people make very weird assumptions.

And when they want me to talk about

neurodiversity in the workplace, they

want me to say something like, eye

contact is aggressive or like that.

It doesn't, it's not true for everybody.

Or like, not everybody thinks

in pictures, not everybody.

This, you know, there's, there's diversity

within and, and between these labels.

So I think normalizing differences

and rethinking about deficits as of

just a mismatch between the thing

that we're asking our brain to

do and what our brain is good at.

And to your point, strength

building, working with the nature

of our brains, working with the

things that we're passionate about.

'cause literally no one.

It gets lit up by doing

boring things no one does.

And that takes us back to curiosity.

Do you know that when

your brain feels curious?

It is.

First of all, it requires safety.

You cannot feel curious

when you're not safe.

And when your brain feels curious,

it emits dopamine in anticipation

of an information rewarding.

The same interesting basal

ganglia that looks for food.

Treats the human brain treats

information as a reward when it's

something you're curious about.

And when that dopamine comes online, it's

dopamine is something that is not actually

for reward, it's for motivating learning.

So it motivates you to work and it re,

your brain gets rewired more quickly.

So I guess like when you started

talking about your son and then you

said you worked with what motivates him?

My second answer to that person

who's got a kid on a pony is

learn about that kid's what?

Lights them up and put it into that.

We, there's, so there's a study that

was actually done in, I think it was

Nigeria that's so brilliant and so easy.

They were teaching kids math and

they gave them, and this was like

secondary school math, and they gave

them a 10 minute interest survey.

Where do you like to shop?

What do you buy?

Who are your friends?

What's your name?

And then they did this math

instruction where they personalize

the problems or, so yeah, Rupert

went to the store to buy whiskey.

IPA.

Yeah, there you go.

An IPA and and you know, and

then you do the math in that.

And of course you, and I know this because

we're parents the kids who had a a, the

math wasn't taught differently at all.

It was just taught in a context that

the kid cared about, which meant that

you get curiosity kind of by periphery.

Sure.

And they learned more.

And so this is like, in my writer's group,

I had a friend tell me, you're like one of

those moms who puts vegetables in dessert.

'cause I'm curious about the

brain and I don't wanna be.

I'm like, yes.

That's the secret sauce.

Rupert Isaacson: It's interesting.

We have a whole thing within horse boy

method of movement method of, of before.

We see someone trying to, as you

say, get as much info as we can.

Mm-hmm.

And we want to know all the

motivators we want to know Yeah.

If they're into Pokemon, well,

what aspect of Pokemon, you know?

Yeah, yeah.

Who are the characters?

What are the, you know, and we'll,

we'll tailor it all around that.

Yes.

Yeah.

But also what, what do they hate?

Yeah.

And we find that that's as

important too, so, oh yeah.

That's sensory, right?

So mm-hmm.

They hate this sense, so we're gonna great

these things, we can, that's back, perhaps

back to your point about distraction.

Mm-hmm.

We can then try to eliminate as

much as possible those smells, those

noises, those characters, those types

of things from the environment that

we are gonna work in, so that mm-hmm.

And if we then maximize the things

that are the motivators, well then

presumably we've got a better chance.

But one thing I, I often see with

in the therapy world, sadly, is

a lack of curiosity and mm-hmm.

I think within the horse world, this

can be particularly endemic, sadly.

Mm-hmm.

That we horsey people are quite

bossy and quite opinionated.

Mm-hmm.

And we don't like change.

Mm-hmm.

So we hate admitting that maybe

we need to rethink something or,

you know, we'll usually dial on

nail of how we've always done it.

Mm-hmm.

And obviously that's not massively helpful

when we are dealing with our horses.

It tends to make us stuck.

But of course, if we're then trying

to take a therapeutic approach, that

lack of curiosity is going to shoot

us in the foot fairly massively.

Mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

Presumably that lack of curiosity

can't be really endemic because

humans are curious apes.

Mm-hmm.

So here's a question.

Do we have curiosity trained out of us?

Mm-hmm.

And can we retrain it?

Yes.

And what part of the brain do

we need to target for that?

And how?

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Mm.

So.

There are sort of state and

trait differences in curiosity.

Some people are more curious

by nature than others and there

are also different kinds of

curiosity or perceptual curiosity.

People who wanna feel things.

Mm-hmm.

And epistemic curiosity,

which blows my mind.

It's, it's strange as much as it's true of

me, that people wanna know things, wanna

know that jellyfish could essentially be

eternal 'cause they can like go, you know,

go back a stage developmentally, it's

like, how will that ever help me in life?

But it's so fascinating, you know,

Rupert Isaacson: because

it makes you optimistic.

Dr. Chantel Prat:

Yeah.

You're like, oh, somebody can do it makes

you, it generally, generally optimistic,

Rupert Isaacson: which means you

assume better outcomes, which

means you probably will get them

Dr. Chantel Prat:

right.

And so there in the jellyfish example

you have highlighted, where curiosity,

like where does it come from and

can we, is it trained out of us?

Absolutely.

Yes.

I think, and depending on the

discipline, sometimes it's very explicit.

Like, don't ask questions, do what I say.

And, but we, I think we know the recipe.

I think there's a pretty

good recipe for curiosity.

And and my favorite is a model

by Gruber and Ranana Char.

Char and Ranana was one of my

professors in grad school, and

it's called the PACE Model.

So it's easy, PACE.

So number one is predict.

So, if you think you know the answer,

if you think you know what's right,

you're not going to be curious.

Right?

It's, and that's like to that

point of we get stuck in mm-hmm.

In habits.

If something surprises us if something

doesn't go as planned or we find

ourself in a new situation, that's

where we have the first opening.

That's where I think, like for me,

like humility about what I don't

know, keeps me like always curious.

So, so prediction, failure

is the first trigger.

It needs to be something you

don't know everything about.

But also if it's something you

know nothing about, you're probably

also not curious 'cause you're

trying to make connections.

You know, you wanna integrate everything,

everything into your knowledge of

the world and your place in it.

Then the, the important part, I think

is the assessment number two, am I safe?

You know, and if you're a hunter gatherer

and you find something unexpected, if

you make a wrong turn on Google and

you find yourself in the wrong place,

if you're in a situation and your

conversation is not going as planned,

the question is, am I physically safe?

Am I psychologically safe?

And I think this is something

that corporations haven't been

spending enough time with when