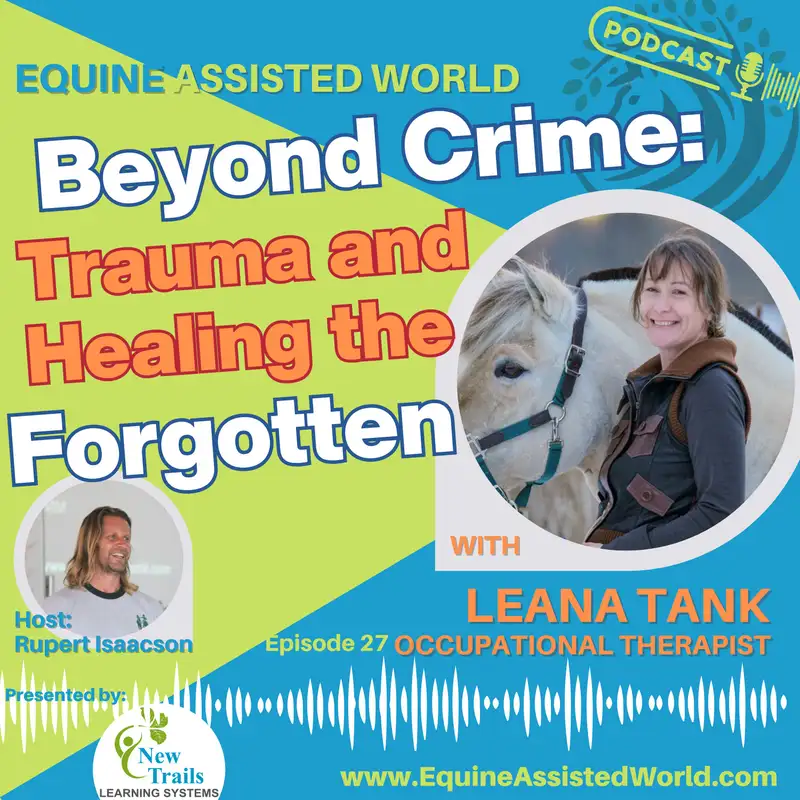

Beyond Crime: Healing Trauma, Restoring Humanity with Leana Tank | Ep 27 Equine Assisted World

Rupert Isaacson: Welcome

to Equine Assisted World.

I'm your host, Rupert Isaacson,

New York Times best selling

author of The Horse Boy, The Long

Ride Home, and The Healing Land.

Before I jump in with today's

guest, I just want to say a huge

thank you to you, our audience,

for helping to make this happen.

I have a request.

If you like what we do, please

like, subscribe, tell a friend.

It really helps us get this work done.

As you might know from my

books, I'm an autism dad.

And over the last 20 years,

we've developed several

equine assisted, neuroscience

backed certification programs.

If you'd like to find out more

about them, go to newtrailslearning.

com.

So without further ado,

let's meet today's guest.

Welcome back to Equine Assisted World.

Most of us who work in this field

either work with kids or who might

have a variety of neurocognitive

conditions, sometimes mixed with

physical or young adults with anxiety.

I, you know, young adult autism, that

sort of thing, or, you know, perhaps

trauma and also perhaps veterans,

you know, but there's a whole other

group out there that I think a lot

of us don't work with because it's,

it's really a specialized thing.

And so we're very lucky to have Leanna

Tank here who's an occupational therapist

from Grand Rapids, Michigan, but also a

very accomplished horse, woman and works

in the equine assisted field as well.

And she works with a population

that I think most of us would

feel intimidated to work with, let's

say and takes it in her stride.

And so I want to delve

into Leanna's Toolbox and.

What, what makes her able to

do this and to do it so well.

I'm gonna let her explain what she does.

So without further ado big drummer

of the amazing Leanna Tank, one

of my great heroes, actually.

You are one of my great heroes.

Leanna, can you, can you talk to us

about who you are and what you do?

Leana Tank: Sure.

Yeah.

So, yeah, thank you for having me here.

It's quite an honor to be included.

You've had many, like brilliant,

amazing people on this podcast,

so it's great to be here.

Yeah, I mean, I, I'll say first off that

the population I work with does struggle

with some pretty extreme the extreme

end of the mental health continuum and

the challenges that people can can face,

you know, in the course of their lives.

And that can be a little bit

shocking to hear about as, as

just like a regular person.

So I just wanna validate that

and just give people a little

bit of a warning or a heads up.

Like, like the, the challenges of the

people that I work with are quite extreme.

I work in.

Residential behavioral health.

So these are programs for

people who need 24 7 support in

the community, staff support.

They come to us from the state

psychiatric hospitals, the prison

system, criminal justice system.

They have different diagnoses

like schizophrenia, many on the

autism spectrum, personality

disorders, cognitive impairments.

Many, many, you know, a lot of they

might have dual diagnoses, so they

might have schizophrenia and a cognitive

impairment and things like that.

Many

have committed crimes and so they're

part of part of their, part of their

treatment because they have been found

not guilty by reason of insanity is

to come and work in our programs.

So those are, that's the population

of people that I'm working with,

and they really are people who

are on the margins of society.

They really don't have a voice.

They're really not talked

about something I find.

Quite often when I'm meeting

people and they're asking

me like, oh, what do you do?

Who do you work with?

And I I tell them people

are often not very curious.

I don't get a lot of other questions.

I think it it, they make

people uncomfortable.

I think in our culture we are not great

at looking at that like darker side

of our natures in ourselves or in,

in, just like the culture in the, in

the, in our society, we want to kinda

label them as other and as monsters

and we want to send them off to jail.

We wanna punish 'em.

We want to stick them in the state

hospitals or say that they're

evil and send them to hell.

And they really get defined, I think,

by the things that they've done because

they, that it can be pretty extreme.

But in my experience, like

they are not what they've done.

They're, they're honestly,

they're like the most sensitive

and vulnerable of all of us.

They're they're kind of the,

the part of our society that is.

Hearing the burden or paying the

cost of like the breakdown of

our, our care systems and our

kind of social support network.

And they are the ones who are

growing up in the foster care system.

They're the ones born to families

that maybe they were exposed to drugs

and alcohol and utero, and they were

born with a nervous system and a brain

that's just wired really differently.

And then from the get go, they're already

in these institutions and systems.

There are really, really sensitive

neurodivergent folks that just

get taken advantage of or put in

the wrong place at the wrong time.

And really they, they, they could

be any of us, you know, like any of

us are capable of those extremes.

If we're put in the right set

of circumstances or we're one

calamity away from a brain injury

or a serious condition, that

dismantles our ability to regulate

ourselves and control our behavior.

And I think it is hard for somebody

with a, a brain that is fully in control

and, and, and capable of managing.

Fight and flight reactions to

understand what it's like to be

someone living in the world that

doesn't have that same capability.

So, so yeah, like I, I really want to be

able to do them justice and be able to

kind of express what's, you know, very,

very human, fully human, fully unique,

creative, interesting, you know, people,

they are, and I absolutely love working

with 'em, and I find it to be incredibly

fulfilling and interesting every day.

So, so yeah, I'm glad to be

able to be here and try to

be a good advocate for them.

Try to be a good voice for them because

more and more I see actually less and

less of a place for them in our culture.

Our culture kind of wants to, to

pretend that they're not there.

So

Rupert Isaacson: let me

play devil's advocate then.

I mean, you, you, you let slip two

words, I think, which were good clues.

One was monsters and

the other was extreme.

Just to be clear, I don't

want to trigger people.

Are these people who have done

things that society would de

monstrous or that we would.

With good reason, say that's

monstrous and it and extreme.

And then if that's the case, how does

the act of doing something monstrous,

which perhaps cost somebody else their

life and perhaps cost somebody else their

life in a horrible way, how does that not

define the person who committed the act?

I think that's a fair question

that many people would ask in that.

So whether or not one should

ask that question, I think

it's a natural question to us.

What, what do you say to that?

Because your perspective is so unique.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

You know, and I've worked with a

number of people who have you know,

committed crimes of that level of

severity who have done things like that.

You know, for the folks that I'm

working with, with their mental health

conditions, often they're in a state

of like psychosis or extreme distress

when something like that happens and

and then they're left really you know,

dealing with the trauma of that event.

I will say, you know, humanity

is extremely, adaptable

and extremely resilient.

I have worked with people who have

been through things, you know, either

things they've done or things that they

themselves have experienced that are just

kind of beyond imagining and they move on.

I think that a big part of, of healing

the, the trauma of something like that,

that has happened and I've, I've been

able to like witness this process.

Like it's been such a privilege

to like, be part of it and witness

it is moving from being defined by

that thing that happened and kind

of being always hypervigilant to

reminders of what happened or, you

know, per, you know, that that guilt

or that having that self-perception

colored by those events and through

through kind of that healing process.

And a lot of it is relationships with

somebody who can be very nonjudgmental,

who can help them see themselves

in different ways and, and also.

Organize those events and organize

kind of what happened and understand

it through the lens of how their

mental illness affected them.

And, and you know, just, just trying

to find a different perspective on it.

See people be able to integrate those

events, kind of figure out the lessons

that they've learned figure out how

to kind of come into alignment with

what happened and how they, what, how

they are going to use those things

to come forward and help others.

And honestly, something I've seen

several different times, and this is

how I know that a person is kind of

on that, on that path towards more

integration and more healing, is that

they will tell me that they want to

help others and they want to use what's

happened to them to support other people.

And they will kind of even take

those other people under their wing.

They'll be.

A positive impact on the other

people that live in those programs.

They'll kind of be a mentor.

They will take on that role.

So that's something

I've seen several times.

It's really something.

Yeah,

Rupert Isaacson: I guess what,

so that people can get their

head around it because it's

outside most people's experience.

Most of us, if we think of someone

has done something monstrous and

they're locked up the first, you

know, it's, it's, it is usually a

Hollywood type of idea that comes in.

So I think the first picture

that a lot of people would

have would be Hannibal Lecter.

Mm-hmm.

And so the Hannibal Elector explains

in great clarity and detail and with

a sense of vindication that he's

right for having done what he did

and to do what he still wants to do.

Which of course is what makes him scary.

'cause he's not just that he does

these things, but he thinks them

through and he plans them and,

you know, executes them as well.

I think it's very difficult for

people not to have that idea.

And however, as you pointed out, these

are people who were actually found not

guilty because of their mental conditions

in, in the English.

Lexicon English, English lexicon

of British English lexicon

of sort of criminal justice.

I think what we call that is

if someone, it's premeditated,

it's malice, a forethought,

you know, that's the difference

between murder and manslaughter.

I think for example if somewhat it was

planned out, it was done in cold blood,

it was rather than in the heat of the

moment somehow, or blah, blah, blah, blah.

Of course adding psychosis to

this is a whole other thing.

And

is that something, which I think there

needs to be a greater understanding of

that psychosis can sort of happen to

people and that when someone is in that

psychotic period, they're not who they

were when they were not in that thing.

And then you also said something which

made me prick up my ears, which is

that one might be just one calamity

away from something that happens to

you that, an injury that causes that.

And I think you put your finger

on something there, because I,

I do know people who sustained

head injuries, who then went on

to do really quite crazy things.

And that seemed cruel and uncaring.

Because some part of their brain had

been damaged and, and, and this could

actually be sort of traced and traumatic

brain injury and criminal behavior.

Actually it's one of these areas

that's getting more studied now,

but I don't think there's a lot

of understanding of wider society.

But this of course is

your bread and butter.

Can you just talk to us a little

bit about this difference between

premeditation and non premeditation

psychosis and nons psychosis?

How you can be one person in one

moment and another person and

another traumatic brain injury.

I think this is really useful for,

particularly for people in our field.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

Yeah.

And I think it's important to point out

that people with mental illness are much

more likely to be victims of violence

than to actually be violent themselves.

That's very true.

They are like three, I just saw these

stats like three times more likely

to be victims of a serious assault.

Mm-hmm.

And then more than half, I think

of like police killings in the

US are towards people with a

mental illness or, or disability.

And that's a lot of the folks that

I know that have gotten wrapped

up in the criminal justice system.

It's altercations with police.

They were, you know, being unusual in

public or something, you know, and I.

The police were called and the police

don't understand the mental illness

and they escalate and, and, and this

happens all the time, all the time.

There's just not a good understanding.

But I think to go to what you were

asking about, you know, with something

like psychosis which many people with

schizophrenia may experience but also, you

know, people can have psychotic episodes.

When you have bipolar disorder, certain

medications can induce psychosis.

People, older adults, when they are in

the beginning stages of like Alzheimer's

and dementia, can be pushed very easily

into psychosis, just with a little bit

of a change in their body chemistry.

They get a urinary tract infection

and they start experience psychosis.

And psychosis is really a disconnect

from like a shared reality.

So, there's different like

chemical processes that go on in

the brain and it can be different

depending on that diagnosis.

But people will develop delusions.

So ideas that.

Are not like logical or

what we would deem logical.

They might, sorry.

They might have hallucinations.

So they might see things

that other people don't see,

Rupert Isaacson: hear

voices in their head.

Leana Tank: Yep.

They might hear voices in their

head that seem very, very real.

And I've worked with people who

are extremely distressed by the

voices they hear in their head and

can barely maintain a conversation

because they're so distressing.

And then I've worked with people who

really enjoy their, the voices that

they hear or might perceive people

around them that they see as like

their family or like their friends,

and they find them very comforting.

There's different levels of insight.

Some people can kind of be a little bit

aware that they are not experiencing

like the same reality as other people.

And then some people have absolutely no

insight at all and there's no arguing.

So there, there's different

shades and levels to it.

I think when it becomes an

actual dangerous situation is

when it is really fed by fear.

So when the person is in an

extremely fearful state, when the

delusions or the hallucinations are

terrifying and scary, sometimes they.

Present as like demonic or they

present as they're being persecuted.

That's when you worry a little bit

about violence because the person feels

like they have to defend themselves.

So it's usually pretty.

Right.

Rupert Isaacson: And if they you a demon,

then all bets are off in that moment.

Yes.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

And any person, if you can kind

of like for an empathy experiment,

you know, imagine if you truly,

truly believed that a demon was

coming for you and, and saw it.

I mean, it, it's, it's a

very multisensory experience.

So your entire body's sensations

will perceive this as reality.

And the parts of your brain that are

gonna check that and say, maybe this

isn't happening, they are just offline.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

I think, I think it's, it's easy to

underestimate the power of the amygdala.

Yeah.

It perceives that a threat has

gone beyond a certain point.

It's, yeah.

Well, its job is to tell the body to

produce cortisol to shut off thought

so that one acts and doesn't think.

Yeah.

It's, it's interesting.

Well, obviously it's fascinating, but.

I know, I think a lot of people have known

friends or family members, or close people

close to than us who've gone through

psychosis and this feeling of helplessness

that this person is unreachable

and yet you reach them.

So there they are.

Whatever has happened has happened,

and they find themselves in the

situation now living where they live.

And Leanna Tank walks into their life.

What's your objective?

You know, a lot of people,

again, it's very natural.

It might not be right,

but it's very natural.

Think, well, they've done these terrible

things, they should just be locked

up and the key should be thrown away.

That's just it.

Die in a dungeon somewhere.

But of course

actually life goes on and

somebody has to be there to make

that a life that has meaning.

Again, you can hear the devil's advocacy.

No, they've lost the right, you

know, they've forfeited that, right?

They should suffer and they should

live in a situation of unpleasantness

and suffering as punishment for

what they've done, even if they.

Were not themselves or didn't know

what they were doing or whatever.

You then arrive, actually,

let's back up a bit.

You weren't, you didn't come out of

your mother's womb doing this job,

so how did you end up doing this job?

And then let's get to what happens

when, when you arrive in that world.

So how, yeah, where does it begin for you?

How did you get into this?

Leana Tank: Oh gosh.

Okay.

Rupert Isaacson: 'cause stay us way back

because, you know, there must be stuff in

your childhood that prepared you for this

kind of, this kind of work that had to be.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

I'm like, trying to

think how far back to go.

Rupert Isaacson: Because it's interesting

when, you know, often when I'm asking

people about childhood in this, in this

type of work, it's often about, well,

you know, some sort of trauma or that,

but I, but we often overlook actually

the things that set one up really

advantageously in one's childhood.

And so you, you do such

extraordinary work.

It must have its roots in some deep

sort of sense of security or something.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

You know, I mean, I think that at

my core I'm, I'm very, very curious

and very interested in kind of that

full breadth of the human experience.

And I was very drawn.

Occupational therapy.

I, I studied in, in college, I

studied psychology and literature

and philosophy, and I, I've been

like a big reader all my life.

And I was drawn to OT because

it is very, very broad.

Occupational therapy is at its core, just

about using what people love to do as a

way to promote, like healing and meaning

to help people do more of the things

that they love and are important to them.

And then to also use meaningful, what

we call occupations are really like

anything that somebody might find

meaningful whether it's, you know,

playing chess or, or taking a walk

outside or riding a horse or whatever.

It can be anything.

Using those things to promote healing.

So it's, it's really broad and you can

apply it across just about any kind of

population, you know, from kids to older

adults, to people recovering from a hip

replacement to people with schizophrenia,

you know, in a locked institution.

I really like that because I don't

like being kind of pigeonholed and

siloed to one dogma or one set of

beliefs or one kind of approach.

I grew up in a pretty

like fundamentalist home

Rupert Isaacson: fundamentalist criticism.

Leana Tank: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

And that never, how did that prepare

Rupert Isaacson: you for, for seeing

the breadth of the human experience?

'cause that's presumably about narrowing

the human experience, is it not?

Leana Tank: Yeah, and it, yeah.

And I, I feel like growing up

in that kind of a, it was a

very, very, like, loving home.

And, and, you know, just like

a great family good community.

But it was the, when you grow up

in a very fundamentalist Christian

home, it's really about molding you

to be the person that, that that

belief system wants you to be and not

really supporting you in expressing

who you really are or really like,

it's more about.

You figuring out what's the right

thing to feel, what's the right way

to behave, what's the right emotion

to have, and not like tapping in and

understanding what you actually do

feel and what you actually do believe.

So I feel like that whole process and

being able to figure out how to do

that came like really late for me.

So I almost how get them was

really, gosh, like, like college

and even beyond, you know?

And I think as I have like worked through

figuring out, you know, how to actually

engage with that it really motivated

me to like help other people do that.

And also to work in a way that is

like, how can I help these people who

are not acknowledged, are not seen,

are not valued for who they are?

How can I help them figure out who they

are and, and be accepted for who they are?

And when you are coming in to work

with somebody in these settings, you

have to walk in very nonjudgmentally.

You have to, to the, to the extremes,

dismantle your judgment about what

they deserve and what they've done.

You have to be pretty radical in in

accepting kind of who this person

is and, and who they've been in

the world and be ready to meet that

person exactly where they're at.

So it's always really interesting.

I will do a little chart review

and read like what is, you

know, what has this person done?

What's their history?

And it always reads pretty rough.

It's always a little scary

and a little shocking.

It's like, I mean, how would you like

it if before I met you, I read the

rap sheet of every terrible thing

you've ever done in your life, right?

Like all probably the worst moments

are all in these people's charts for

everyone to read before they meet them.

And then almost always the person I

meet is like completely different.

Like you would never imagine

that that was their history.

It's very, very rare

that I meet anyone that.

Actually like, wants to hurt people or,

you know, has any intention of doing that.

It's all these things that have

happened when they were really

pushed into their survival state.

But I do meet people that like, don't

really wanna work with me or maybe

don't, maybe they're pretty disconnected

from reality and they're hard to

reach or they've been therapized and

in, in institutions for so long that

they're just kind of like, get lost.

I don't want, you know, I don't

want anything to do with you.

But I feel like I have developed

three different ways, like a, a way

of kind of approaching people without

an expectation, without an agenda

and being just very, very open to meet

them exactly where they're, they are.

And where they are is completely fine.

And often when I am asked to go

meet with someone, it's because

the team has an idea of where they.

What they should be working on.

Maybe they haven't showered in a year

and they want me to help them do that.

Maybe they struggle with managing

their emotions and they want me to

work with 'em on that or whatever.

But I kind of have to put all

that to the side and just meet

this person and be like, well,

what do they think is important?

What's like,

Rupert Isaacson: established

relationship effectively?

Leana Tank: Yes, yes.

And there's people, and I have the

luxury of doing this, where I can sit

down and what they wanna do is like,

talk about the rings and the jewelry

that I have on and rocks and stones, or

what they wanna do is, you know, just

listen to music, you know, on my phone.

And I can do that with 'em for

weeks and weeks and weeks to kind of

establish that relationship and then

figure out like what's important to

them and where do, where do they want

to grow, where do they wanna develop?

And a lot of times those other things

just kind of fall into place when

they feel like they have like a safe

relationship when they feel like they

have more meaning in their lives when they

feel like they, you know, are actually

Rupert Isaacson: heard.

Leana Tank: Heard.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Okay.

How do, okay, you as growing up as

a young fundamentalist Christian,

were not probably schooled in this

type of non judgmentalism, right?

Because any dogmatic religion

has pretty clear judgements.

You're either in or you're out.

You either follow the rules or you don't.

You're either saved or you're gonna hell.

And it's also a punishment

based punishment and reward

based culture, right?

If you do these quote unquote bad

things, you're going to hell and you're

probably be ostracized and perhaps even

physically punished, you know, here.

And that includes if you just

don't toe the line we'll,

you know, won't support you.

How did you get from that to what

I think is, and I guess, I guess

what I'm, what comes to mind here is

what you are actually talking about

is what Christianity is supposed

to be, which is love thy neighbor.

Don't be an asshole.

If you are an asshole.

It's entirely forgivable forgiveness.

Redemption.

Do you think that some really discerning

part of you as a child thought?

Yeah.

All that punishment stuff, that's

all shame, but all that love

thy neighbor, redemption stuff.

That's good shit.

And what made you able to discern that?

Because I don't think everybody

who grows up in that can

go back to your young self.

Yeah,

Leana Tank: yeah.

You know, I mean, I think part of it

was, part of it was just baked in me.

Mm-hmm.

I can remember being very, very young.

I was a very like, magically

minded animal loving, you know,

kindergartner, first grader.

And even, even in elementary

school hearing that was the

big, like environmentalism was

like a big burgeoning thing.

And I remember hearing about it

and being like, that sounds cool.

And then in.

Church or wherever, and the dog mutt

was like, oh no, we don't believe

in environmentalism and we don't,

you know, this is, it's all about

supporting people and humanity and we

don't, you know, we're, we want Man has

Rupert Isaacson: dominion.

Yeah.

Man has

Leana Tank: dominion.

Yeah.

And, and that never

really made sense to me.

I remember just being kind of

like, oh, I don't know about that.

And I think I, I read a lot.

I, I, when I went to college,

I studied philosophy.

My, I had a really deep interest in

like other cultures and traveling.

My grandparents were missionaries

in Africa and South America.

So I grew up with all these stories

about my dad growing up in these

other places that I thought were

really fascinating and intriguing.

And my mom's side of the family,

my grandfather was like a magician.

And so I grew up with all these,

like, you know, my, my mom and my

uncle had all these like sleight

of hand magician tricks and, and

stories about his life as a magician.

I mean, he was a lawyer, but he

was like a big time magician.

He was like the president of the

International Brotherhood of Magicians.

I, yeah.

So I think I grew up with all these

different ideas and when I went to

college and studied theology I, not

theology, but philosophy, when I

actually started reading and thinking

about the concept of hell and trying

to make it make sense how all of these,

like other cultures of the world, like

90% of like the world's population

would be just kind of resigned to hell.

And somehow the Americans with all of

our, like, you know, our money and our

comfort also happened to be correct in

our beliefs and, and we'll go to heaven.

To me I was like, yeah, that

makes absolutely no sense.

The American.

Yeah.

Yeah.

But I did I, I did like and

believe in that idea of caring

for like the least of these.

And, and when I was just starting to look

at like where to invest my, like my work

and my energy and my time I, it was like,

well, that seems like a worthy place.

You know, to put my, to

invest my, like, work life.

I, I really loved, I read Oliver

Sacks is a, I read his work in

college and it was really, really, it

really like connected with me and I'm

actually reading his letters right now

Rupert Isaacson: for a hat.

Leana Tank: Yeah, he was a neurologist

and he, but he was a very like,

human kind of poet, neurologist that,

like, he wrote these case histories

of these really extreme cases of

people, people's experiences with like

different neurological conditions.

But it was all about how they, how they

kind of lost all foundation of like who

they are, who they were in the world,

how they experienced life, and then

how they kind of remade it and, and

adapted and, and kind of found their

humanity and worked those conditions into

their, into an another form of meaning.

And I just found it to be really,

really beautiful and interesting and

I'd never, I didn't, wasn't even aware

of, you know, it's just like beyond this

imaginable experience, what, how people

can wind up living and still having, I.

A very full, meaningful, rich life.

And that just really fascinated me.

So yeah, I feel like I'm kind of like

wandering away from the question.

I don't even remember where we started.

No, I, I think, I think you got that.

And

Rupert Isaacson: so, and it leads me to

a, a triple question, which is this one.

So how does one develop the

ability to approach without agenda?

And then my devil's advocate

questions, is there actually no agenda?

Because okay, maybe they haven't

showered or they're not communicating.

So presumably you're brought in

there for some sort of healing.

Is healing an agenda?

And is th that an okay agenda?

You know what I mean?

So just

Leana Tank: mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

Your thoughts on this, really?

Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Yeah.

I, okay.

Rupert Isaacson: If you're in the

equine assisted field, or if you're

considering a career in the equine

assisted field, you might want to consider

taking one of our three neuroscience

backed equine assisted programs.

Horseboy method, now established

for 20 years, is the original

Equine assisted program specifically

designed for autism, mentored by and

developed in conjunction with Dr.

Temple Grandin and many

other neuroscientists.

We work in the saddle

with younger children.

Helping them create oxytocin in their

bodies and neuroplasticity in the brain.

It works incredibly well.

It's now in about 40 countries.

Check it out.

If you're working without horses,

you might want to look at movement

method, which gets a very, very

similar effect, but can also be

applied in schools, in homes.

If you're working with families, you can

give them really tangible exercises to do

at home that will create neuroplasticity.

when they're not with you.

Finally, we have taquine

equine integration.

If you know anything about our

programs, you know that we need a

really high standard of horsemanship

in order to create the oxytocin

in the body of the person that

we're working with, child or adult.

So, this means we need to train

a horse in collection, but this

also has a really beneficial

effect on the horse's well being.

And it also ends your time conflict,

where you're wondering, oh my gosh, how

am I going to condition my horses and

maintain them and give them what they

need, as well as Serving my clients.

Takine equine integration aimed

at a more adult client base

absolutely gives you this.

Leana Tank: A couple of

things to say on that.

I'll start with in, in my experience,

the most powerful real healing has

always come from that person themselves.

So I really don't, and I've gotten more

and more and more to where I feel like.

My role is really just to

help remove whatever barriers

are there for that person to,

you know, find what healing is for them.

And it can just be these really

small shifts in like greater, greater

participation, greater connection to

themselves, greater connection to others.

It's for a lot of the people that I work

with, like they're not going to whatever,

what it, what even is healing, you know,

like what is healing isn't like they're

fixed or they're cured or they're healed.

It's like, well, it's

difference between healing.

And

Rupert Isaacson: it's a good question.

I think in my mind there is a big

difference between healing and cure.

Like people often think knowing

when I went off to Mongolia with

Roman, for example, oh, you were

looking for a cure for autism.

No, I wasn't, but I was looking for

healing because we were all suffering

and we did find it, but the autism

wasn't what was causing the suffering.

It was reactions to other things.

But yeah, so I, I think that is just

worth drawing attention to that.

Healing and cure are two

slightly different things.

And so, but, so Go on.

Yeah.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

Yeah.

And I think that is definitely the,

the way I am operating and the way I

am looking at things like a lot of the

people I work with are always going to

need some degree of like, support just,

just to be safe and to live in the world.

But often they are really, really

disconnected from themselves.

They're disconnected from other people.

They're not, they don't have a lot

of meaning or purpose in their lives.

There's, their days are

kind of full of like

nothing avoid.

So if I'm able to even shift that a

little bit and, and bring in some purpose,

bring in some movement, bring in some

energy, some vitality, some, you know,

just yeah, any kind of like change in

that I see as as progress as healing.

And I've seen small shifts and I've

seen really big shifts and I've seen,

I've worked with people that I've been

like, I didn't do anything for them.

And then a year later I, I will hear

a story that, you know, actually there

was an impact or there was a big change.

So, but generally I.

If I come in with some kind of

preconceived notion or idea of like,

what that's going to look like and what's

gonna help them, it doesn't go very well.

And so coming in with no agenda and just

really, really radically listening to

that person and where they are and what's

important to them and what they feel could

be, you know, would, what that would mean

for them is, is always the way to go.

And then my job is just to

be like, yes, great idea.

How are we gonna do that?

You know?

And honestly, the systems

that we're working in are so

dysfunctional and so broken.

It's, it's really basic

stuff for a lot of people.

You know, in, in, in the program where

our probably most intense, it's like

locked all men mostly in that like

not guilty by reason of insanity.

So they have, you know, all part

of the criminal justice system.

It sounds really gnarly.

Most of the time what they

wanna do is take a walk outside.

You know, I take people if

it's safe for me to do so.

And, and most of the time it

is, I'll just take them walking.

We live by.

They're about 15 minutes from

Lake Michigan, which is beautiful.

And I'll just take them out to the

lake and we'll walk on the beach.

And I'm like one of the only ones that

does that kind of thing, you know, like

it's just not really part of the medical,

healthcare system frame of reference

to see that as like a healing activity.

But for me it's like a no brainer.

Like let's go see some beautiful nature.

And I just did that recently and had

this young man who was really struggling

and it, it's been like a cold winter and

there was, we went out to the lake shore

and there's just this little patch of

blue sky and he like pointed at it and he

was like, that, that's telling me that,

that God's telling me he's got my back.

You know?

And and that led to a really, you know,

beautiful conversation about like,

yeah, like that, that's beautiful.

That's such a, like what a lovely

way of like, nature showing you

that like it's there for you, it's

showing up for you and like what else,

what else tells you that, you know?

And he's like, well, sometimes I

see birds and that, you know, that

tells me everything's gonna be okay.

You know, and like, and just conversations

like that that help give people a sense

of connection, a sense of like, insight

and get them thinking, thinking along

those lines I think is like, really

healing and letting, you know, bringing

people into nature and then letting nature

show up and do what it's gonna do, and

then be just prepared to frame that and

organize it and kind of like give them

a way to synthesize it is, is one of the

most powerful and easiest ways I think.

And then the other thing in that program

that everyone wants to do is cook.

That's interesting.

Why?

Yeah.

A lot of them have been in prison

or institutions a lot of their lives

and they never, ever got to cook.

They don't know how even in that facility,

Rupert Isaacson: do they tell you, or

is this something that you suggest?

Leana Tank: A lot of times it's like,

the only thing they wanna do with me.

So it'll, it'll be like,

what do you wanna do?

Nothing.

And then maybe I'll give options

and they'll be like, actually,

yes, I would love to make brownies.

People love food.

Cooking is a really, really just

foundational functional skill.

Like, if they're gonna like, move on from

there and, and everyone wants to be more

independent, you know, for, you know.

The day-to-day life of most of us of like

driving a car, having a home, having a job

is like beyond the wildest dreams of like

most of the people that I'm working with.

So if they feel like they can like

work towards skills that will give them

some level of independence, they're

a little more motivated for that too.

And so I'll do whatever I can to,

like, I'll, I've like rigged up

little hot plates so we can like, make

burgers or pancakes or I'll take 'em

to another, there's other programs

that have kitchens where we have

kitchen access and we'll cook things.

And if you think about like

promoting a sense of safety and

like community and connection like

cooking is, is just great for that.

You know, if you think about like,

Rupert Isaacson: it's

wellbeing, I guess, isn't it?

Yeah.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

And like if you are like cooking in

the kitchen with a friend or something,

or making dinner with a friend or,

you know, it's just a very like,

safe, connected, enjoyable, ancient,

ancient thing to, to be engaged in.

And I, that's, so many of

them wanna do that with me.

So I try to do that as much as I can.

Rupert Isaacson: This was actually,

you've sort of partly answered, but I, I

still want to pose the question because

I think it bears more discussion, is,

you know, I, I would imagine that quite

a few of the people are in a fairly

profound state of despair, and when

you're in despair, you lose motivation.

So if you were to say, well, I'm, I, I,

I do what they like the way they love

music, or they want, but I should imagine

that a lot of people have lost a sense

of what they like and what they love.

Leana Tank: Mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: But what you've just

described is effectively nature, because

I would put cooking in that category too,

because you're using natural elements,

natural processes for a natural process.

When you are encountering that nihilistic

despair that people have given up,

is, is nature always the key?

Leana Tank: That is usually

the easiest, most effective,

most powerful thing to access?

Yeah, I would say.

Rupert Isaacson: So.

Why is that not prescribed?

Leana Tank: That's a very good question.

Rupert Isaacson: What do you

seriously, why given that, I think

deep down we all know this, right?

And that mental health started

with the Quakers and asylums

and asylums were supposed to be,

asylum means sanctuary, right?

That's its actual meaning that the,

that they created gar effectively

gardens that people could rest in and

come back to themselves in and so on.

And so, and we've known this forever

and you are now getting some physicians

prescribing nature, but just begun

to happen, I think, post covid.

Why do you think that

given that, you know,

intelligent people are

helping to create the policies

that affect people in mental

health institutions, what, yeah.

Why isn't it just a

fundamental, what's blocking it?

What,

Leana Tank: yeah.

I mean, I think a lot of it is just the

state of our medical systems is very,

the, the perspective is very mechanized.

It's very reductionistic.

So the focus is much more on medications

behavior management, behavior plans

and you know, things like that.

More focused on diagnosing, prescribing

and there's just not as much

thought put into the environment.

The indoor environment, the outdoor

environment things are pretty siloed.

There's, you know, lawn care people that

take care of the outside and then there's

maintenance for the inside and yeah, it's

just that whole picture isn't considered.

Even just the consideration of like, the

impact and power of like the culture and

the community in of a program can have

such a powerful, powerful influence on

that person's progress and their healing.

Because, I mean, our neurobiology is

not to be like in this vacuum, like

our brains and nervous systems are.

Designed to be always engaging with and

connecting with and resonating with the

other people around us and the nature

around us and the environment around us.

And that is like the number one most

powerful de determinant of kind of

like where someone is gonna be, you

know, what they're gonna be doing

with their time, you know, what

kind of state they're gonna be in.

But that's just, it's, it's

a very complex, dynamic

system that is not linear.

And I think that the medical system

wants everything to be very linear.

Linear and very, like A plus B equals

C, and let's just change this one thing,

or let's just look at it this one way.

Or they look at that person in a

vacuum and they don't look at the

whole web of every determinant that is

contributing to that person's health.

Rupert Isaacson: I guess there's

also presumably a desire both

negative and positive for control.

Mm-hmm.

To say these people are

outta control, not safe.

They're not safe to be

out in the community.

Mm-hmm.

So therefore a walk in nature is.

Out in the community.

We can't risk people.

We can't risk these people.

You know, the service user, if you like,

losing control, having a psychotic, you

know, and while one can understand that

you seem to some degree to be putting the

lie to that, which is interesting to me.

Are you ever afraid, let's say you take

them out to Michi late Michigan, that

they're gonna do something crazy that

you yourself are in danger or that other

people on that beach could be in danger?

I mean, admittedly I've been out to the

late Michigan beaches, unless you're

going to a hotspot, it's a lot of,

you know, it's wild what, you know?

Mm-hmm.

So it's not like there's a ton of

people around, but nonetheless is it

irresponsible to take them out like that?

It's, you know, just, just talk,

talk through all these complexities

that I could see going through

the heads of policy makers.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

You know, I mean, I'm always mindful of

who I'm working with and I know them well

and there are safety measures in place.

There's assessments, there's safety

plans, and there, there's all of this

structure in place to kind of determine.

Levels of safety for people

going in the community if

they need, I presume sometimes

Rupert Isaacson: minders, you know?

Leana Tank: Yeah.

Extra people.

Some will say you need two staff,

some can't go with a female,

some have to go with a male.

Like there's, there's a lot of

structure of safety in place

around working with these people.

And I'm very, very mindful.

There are certain people that I will

totally go for a hike in the woods

alone with and feel completely safe.

And there's people I

would never do that with.

And you know, for most of the folks,

when you know them, you know, it's,

you know, when they're in their own,

they're, they're, they're connected

to themselves, they have a good sense

of themselves, they're in control,

whatever, you know, whatever that means.

They're, they're aware of their actions

and they're in a good head space.

And you know, when someone is

struggling, when someone's activated,

when someone is when they're so

higher risk of, you know, them.

Getting triggered into

some kind of distress.

And that wouldn't be a time when I'm,

you know, taking somebody out or maybe

I would have someone else come with

me if I'm trying to take them out to

like help them manage their stress.

But for the most part, when I'm working

with people, they're in a good head space.

They're pretty centered.

They're, you know, not in crisis.

There's a really, really big difference

between when someone is in active crisis.

And that is when you see a lot

of those like really distressing,

challenging behaviors.

And it does happen, but it's,

there's a completely different

difference, you know, when someone

is in crisis and when they're not.

And you're not

Rupert Isaacson: worried that a,

a crisis could be triggered by

something outside of your control.

Leana Tank: It can happen, but you kind

of know your person and you know what

kind of things are gonna trigger that.

And you can take precautions

and I'm pretty proactive.

Like I know how to assess the

situation and I know my person and

I know what might be distressing

to them and I avoid that or I.

Maybe sometimes we're like, I

have people that going out in the

community does trigger some anxiety

triggers some hallucinations.

They might hear people saying mean things

to them that are not like really real.

And that might be something

that we talk about.

Maybe we practice like

some grounding tools.

You know, I, I go, I have a lot of

tools in my little trauma toolkit,

sensory toolkit for helping people

manage that kind of distress.

So that would be something that

we are like building awareness

of and we're working on.

And I can very intentionally kind

of push their window of tolerance

without them going over the edge.

So, yeah, talk to us.

Rupert Isaacson: Take

us through your toolkit.

That's fascinating.

I think a lot of us would like to

have access to those sorts of tools.

Leana Tank: Oh, you know, a

lot of it is, I, I use a lot of

body-based sensory strategies.

So as an OT I did a lot of training

on like sensory integration.

I.

And understanding how we, how our

senses kind of shape our reality,

Rupert Isaacson: our

nervous systems, in fact.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

Yeah.

And it's, it's so fascinating

that it's one of my areas I'm so

fascinated by and, and it really

is a growing area in mental health.

I think people are understanding more and

more that like mind and body connection

and that it's not just that mental health

is this like disembodied thing that just

happens in our brains, but it's really

Rupert Isaacson: Right.

A

Leana Tank: whole bodies, you know,

Rupert Isaacson: it started to,

okay, we understand, okay, let's

take into account the nervous system.

And nature presumably has fewer

bad sensory triggers because we

are organisms, you know, therefore.

Leana Tank: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: But for avoiding

crisis or for dealing with crisis.

Leana Tank: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: Can you be specific

about some tools that you think might be,

'cause we all go through crisis, right?

Leana Tank: Mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

And we

Rupert Isaacson: all crises in our

families and we have crises in ourselves.

This's gonna happen several times a

day just in the most normal situations.

So, because you work on the

cutting edge of this, you know?

Mm-hmm.

Leana Tank: Mm-hmm.

There are some

Rupert Isaacson: tools.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

Well, first is I.

I'm very, very aware of myself

and where my system is at.

I, you know, have a lot, have

developed a lot of tools just

to keep myself like grounded.

Keep myself in kind of that calm,

regulated nervous system state, being

able to use my voice, my body language

my breathing to take advantage of

the, that like mirroring, reflection,

resonance with the other person's system.

You use these tools to kind of become

that like safe anchor for that person.

And it, a lot of it is in like,

the language that you use and

just the way that you show up.

And then I'm always going to try to

organize so using things like rhythm,

so music, offering to play music

offering to you know, seeing like what

kind of music do you wanna listen to?

Let's put it on, let's rock to

the music, let's walk to the

music, let's try to sing along.

I have done a lot of training to, in like

the different nerve nervous system states.

So being able to observe if somebody

is edging into more of a fight response

or a flight response or a freeze, I,

you have to really train your eye to

see those very subtle shifts in that

person's physiology that tell you that

they are starting to become activated.

And it can be as small as like

they're holding their breath.

And being able to, in a very curious,

nonjudgmental way, notice those things.

A lot of times if somebody feels like you

are that aware and noticing that kind of

a shift in their state that alone will

bring about a lot of safety for them.

And

so, so being able to see that and kind of.

Headed off before things escalate

really higher, because once somebody

has really shifted into an activated

fight or flight state, it's a

lot harder to to bring them down.

But,

Rupert Isaacson: okay.

Quick question about the music.

So what if they want to listen

to music that, you know, is gonna

dysregulate them even further?

Leana Tank: I, you know,

I'd give some options.

No, let's listen to Moza.

No, I wanna

Rupert Isaacson: listen

to, you know, whatever and

Leana Tank: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: You don't

wanna then get into it.

No, you can't.

And right time you're trying to

follow them and, but you also know

it's gonna trigger them, so, yeah.

Mm-hmm.

Like how would you,

how'd you deal with that?

Leana Tank: Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Yeah.

It's tricky.

I mean, it, I would maybe give

some choices within that like, area

that they're looking at and I have

like a Spotify account that I can,

like, pick just about anything.

And even if, you know, there's music

that is gonna trigger them, you know, and

it's hard to say like how much it would,

even if something is really, really like

Ragey we might be able to put that on.

And I might still be able, within that,

I'm going to try to organize a rhythm.

I'm gonna try to organize like maybe we.

Get out a drum or we get something out

and we try to like, go along to the beat

with that, you know, to try to like build

a rhythm, build an organization within

like, the music that they wanna listen to.

Or maybe we're gonna go and like power

walk to it, or maybe we're gonna try

to sing along as a way to kind of like

get that energy out in a positive way.

Rupert Isaacson: I'll to it.

That's cool.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

I mean, a lot of times, like I,

I mean I use music all the time.

Rupert Isaacson: And, and I'm just

thinking even let's say that's

what I'm think these tools are so

useful in more mundane situations.

I remember when I was a, a kid and

wanting to listen to lots and lots and

lots of metal and, you know, there was

always in the house that kind of, no,

this is go away from your horrible metal.

I hate your metal.

And that, so of course, you know, metal

became a point of rebellion, but at

no point, for example, did anyone say,

actually, why don't we just clean the

house really, really hard to this metal

to this day, it's my house cleaning music.

Like if you put on metal mm-hmm.

You're gonna get a clean

house, you know, if I'm mm-hmm.

I'm just gonna start cleaning, you know.

So it's interesting that you say

that the idea of sort of taking

even a ragy energy and channeling

Leana Tank: it.

Channeling it,

Rupert Isaacson: yeah.

Leana Tank: Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: Mm-hmm.

You have to be, you have to have some sort

of inner security to be able to do that.

What do you do then?

If they are, if they

have gone over the edge?

Leana Tank: Then it's really

just about safety, you know?

And that's when you have to be aware

of like who else is around, who can

have your back, how working together

just to like keep the situation safe.

And, and, and the folks that I work

with, like when they do go over the edge

and when they are their, their systems

can be so sensitive that that's when

things can get pretty extreme and unsafe.

So honestly, in my nearly 10 years

of working there, I really haven't

experienced much of that myself, honestly.

I have certainly worked with people who

then I hear about like, you know, oh, I

worked, I, you know, made cookies with

this person this morning, and then last

night they destroyed the whole entire

program and destroyed, you know, went and,

you know, threw rocks at the staff's car.

And I'm like, oh dang,

they had a bad night.

What'd you put in those cookies?

Right?

The cookies did not create the

happiness I was hoping for.

But I think because, and some of

it is just my, the nature of my

position, I'm kind of the good guy.

I'm kind of the safe.

Friendly, fun person that is doing the

things that the person wants to do.

And I am, pretty skilled at where

that person's zone of tolerance is

and not to push them over that edge.

Yeah.

And honestly, the things that really push

people into that fight or flight are those

more author authoritarian, controlling

dominance based ways of engagement.

And, and, and we struggle with that, you

know, with like, with our staff and, and

those kinds of interactions because that

can be like the go-to for a lot of people.

That's how a lot of people were raised.

That's how a lot of people feel like

they need to keep things safe and keep

things locked down and in control.

And those are the kinds of ways of

interacting that really escalate people.

And so I have found that if you're not

meeting people with that kind of energy,

like most of the time, that I just don't,

I just don't see that side of them.

Rupert Isaacson: And it's

interesting because, yeah, I,

I obviously in my line of work,

your line of work, you know, ones.

Meeting a lot of people who are dealing

with people struggling with mental

health and getting attacked, punched,

kicked, bitten, can be part of the game.

And one of the things I find really

interesting about talking to you is that

I'm not hearing those stories from you.

Even though you are in there

with people who certainly could

and perhaps do with others,

I don't wanna jinx you, but why do you

think beyond the fact that you don't adopt

an authoritarian escalating approach?

As you say, if they do flip over

the edge, it has to be about safety

and therefore a certain amount

of coercion is going to come in.

You could end up on the

end of a flying fist.

Why don't you, do you think,

Leana Tank: I mean, I think that's,

that's a big part of it, is not coming

in with that mindset of trying to control

people, trying to dominate, trying to,

Rupert Isaacson: there's so

much of it about intention.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

I think, I think the energy that you

bring to it is a huge part of it.

And then I'm also just really,

really attuned to where they're

at and, and listening to them

and kind of me, you know.

Using myself as a way to help

them connect more to themselves.

And I think when you show up to work

people with people in that way, like

you're really a lot less likely to

run into those kinds of challenges.

I'm not saying it can't happen and,

and honestly, if somebody's in active

crisis, I'm not gonna go and try to

work with 'em because that's not really

the time that that's not the time

where I'm gonna really be effective.

Right.

That's not the time when people

are learning and growing,

Rupert Isaacson: that the people

are like, sorry Leanna, they're

just, you know, busy Yeah.

Kicking the doors in.

Yeah.

Would, would you say, okay, I'll

see you tomorrow in that case?

Leana Tank: Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

Yeah.

When, okay.

I'm, I'm torn between going

further into nature or into art

and aesthetics here, because which

actually is perhaps the same thing.

Let's just talk a bit

about indoor environments.

So taking people out into nature.

Fantastic.

Okay.

The indoor environment.

What do you feel is the importance of

art and aesthetics in mental health,

including our everyday mental health?

Leana Tank: Yeah.

I mean, I think it's enormously important.

And it's, that's an area.

Yeah, I mean that's an area that

I've been really trying to like,

think outside the box and in our

programs, because they do tend to

look pretty institutional just because

things get ripped up and destroyed.

And so everything has to

be really, really durable.

But I know, like I, I I read this book

called Healing Spaces that just goes

into so much detail and research about

the importance of the environment on

people's mental health and their healing.

And there was even, I recall a steady,

like done in hospitals that if somebody

is in a room with a window where

they can see outside and they can see

like trees that they heal faster from

medical conditions, then a room with

a window facing like a brick wall.

And there's so many different aspects

of like the indoor and the outdoor

environment, you know, just lighting

and color and the furniture, you

know, and like the sounds and the

smells and even just like the space,

how the space is laid out itself.

And I do a lot of evaluating that when I.

I, I help a lot on the teams

that are deciding like, okay,

this person should go here.

This person should go here.

And we have homes that are specifically

for like autistic adults who have really,

really intense, challenging behaviors

and trying to make sure that they have

environments that are optimal for them.

And it, it can be a challenge to

advocate even for like, let's make sure

they have some rocking chairs, right?

Like, and when you're talking adults,

it's, even with autism, it's even more

challenging because like, you can have

a little swing for a little kid or

whatever, and that's easy, but I've got

like 300 pound dudes that also could

use a swing, but it's a lot harder

to find a swing that's gonna hold up.

And even our rocking chairs, like we

will buy recliners that rock and they

get destroyed within a few months.

So really like trying to figure out

what is gonna do the job, what's gonna

hold up, what's not gonna get destroyed,

what's gonna be cost effective.

It can be really challenging

and the same, you know, putting

art and things on the walls.

It's finding things that are.

Aesthetically pleasing that are not

gonna get ripped down and destroyed.

There was also like research on even

putting up like nature, like fractals,

like, nature art that has like, those,

like repeating patterns and things in

it reduces like anxiety and depression.

I found a research study about that.

I thought it was so interesting to

Rupert Isaacson: me that would

make sense because of course it,

it mimics the environment that

our organism is designed for.

Leana Tank: Mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

Rupert Isaacson: It's interesting.

As you were talking, it made me

remember a guy I had a very fascinating

conversation with once, who his job was

to, it's in England to take pubs that

had a, he worked for the brewery and

his specialty was to take pubs that had

a real problem with violent culture.

Those British listeners know what violent

pub culture can truly be in the uk.

They can be murderous places, the wrong

pubs and turning, turning them around.

And he was this really small expert.

You expect a bloke like that to be, you

know, huge shave and head, you know,

tattoos everywhere, mouth intimidating.

He was this little hippie and I said,

how are you so successful at this

that they pay you the big bucks?

He said, Ru, it's so easy when people

wanna fight, they want a fighting space.

So the first thing we do

is we take that space away.

So almost all violent pubs will have

a big open area with all the seating

Leana Tank: around the walls

Rupert Isaacson: effectively.

Mm-hmm.

So that there's a place

for people to do this.

They might call it a dance

floor, but it's, it's not, it's

a, it's a gladiatorial arena.

The first thing, the first thing

we do ru, is we put nice big

comfy sofas and armchairs in there

that are sort of deep and comfy.

He said mm-hmm.

People sit in them and they chill

out and they sort of don't much feel

like getting up and throwing punches.

That's so

Leana Tank: interesting.

Rupert Isaacson: And he said,

and then we put all sorts of nice

art on the walls, and he said,

and then we play classical music.

We pipe classical music.

And there was another place I knew

of this happening in a bad shopping

mall in another area of England that

can be quite violent, where local

youth were coming and, you know,

smashing up and looting and things.

And it, there was one of the shopkeepers

who'd, who'd read something similar

and he started piping classical music

from speakers that no one could get to.

And apparently he said it was amazing,

Rupert, that, that people just evaporated.

They, they just wouldn't hang out

there because they could be hungry.

Had to take their anchor somewhere else.

And it's, it's so interesting how in

these really practical situations.

What we know chills us out.

A comfy armchair, nice art on the

walls, nice lighting, classical music.

So why on earth again, wouldn't

that be an institutional staple?

Yeah, you know, again, maybe it comes

down to this idea that, well, they,

they've done wrong, they should suffer.

But of course it's, that's not just

in punitive, you know, criminal

justice places that's in schools,

and that's in places where people

are actually supposed to be nurtured.

Leana Tank: Yeah.

And I, yeah.

Yeah.

And I don't think it's, it's that matter

that like, oh, they don't deserve it or

they shouldn't have something comfortable.

I think it's just there's not a lot

of thought and intention given to it.

You know, when I, or the furniture that

is initially bought that will actually

hold up is not comfortable at all.

And, and that just is kind

of what sticks around.

And it's, it's just a cost thing.

You know, our, it's, there's not

much money for these folks at all.

There's not a lot of resources

for them to have a very

aesthetically pleasing environment.

And it is hard that, I mean,

they, when they are struggling.

The behaviors can be very destructive.

So there's holes in the walls,

there's the furniture gets destroyed.

You know, I've had a guy struggle

with autism when he would throw all

the furniture outside of the house

when he was struggling, you know?

So it's hard to have nice things

when that's the situation.

But

Rupert Isaacson: unless I suppose

you make the sofa and furniture so

heavy that it's just so difficult to

pick up that you, and that's Yeah.

We have now.

Yeah.

Leana Tank: Yeah, yeah.

Yeah.

And that's what we have in

a lot of the places now.

But it's that, that kind of

furniture isn't super comfy.

You know?

It's not, and it's not very

aesthetically pleasing.

Rupert Isaacson: Yeah.

No, fair enough.

Maybe, maybe we need to start

enlisting designers for this.

Mm-hmm.

Okay.

So now I would like to talk a little

bit about how you maintain your own

resilience and one of the things that

I think everyone is struck by when they

know you and know what you do is how you

seem to retain this likeness of heart.

That there isn't a, you know, I, I

know quite a few people who work in

difficult situations with difficult

populations that there can be a

certain bitterness that can creep in.

I've never seen that in you.

I also happen to know, of course, that you

are an accomplished and avid horse woman.

And we have a mutual

friend Warwick Schiller.

That's how we know each other.

And those listeners who know

Warwick know that he's a horse

trainer, but also a podcaster.

And his thing is a attunement.

And that if you can attune to your

horse your hor your relationship with

your horse will change so radically

that things that seemed really, really

difficult for impossible suddenly

just become kind of every day.

And he, I think he's been born out in this

and that's why he's as popular as he is.

And I know that you followed

his attunement mm-hmm.

Stuff with horses.

Mm-hmm.

And I, you told me once in a, a

conversation that this had actually

helped you, this attunement

thing had actually mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

Work.

Can you talk to us about how you

understand what, first, what's

your relationship with horses?

How does that impact your resilience?

And then talk to us about this

attunement thing and how one can

transfer sort of species to species.

Just wrap on that.

I, I, I'd like to know your thoughts.

Leana Tank: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Working with warwick's, like attunement

practices absolutely radically

changed the way I was able to work

with the people I worked with.

And I saw so many parallels.

So I'll talk about that in a minute here.

I.

Like I, yeah, I do.

I have my older two, I had two horses, my

older mare, Sonny, who is just my heart.

And I think that having that practice and

working with horses really, really is a

way for me to like, take care of myself.

And I think that to do this kind

of work with other people, you

have to very radically take care of

yourself and be really mindful of

your own mental and emotional health.

And people, our culture, like

really loves a martyr and really

perpetuates that kind of mindset

that you're supposed to just kind of

like sacrifice yourself to your job.

Any job.

Not, not even necessarily a job

in the human services field.

Like, it's just a culture

of kind of burnout.

And so I think for me, having

a horse really helps me keep

my own mental health level.

But I got involved in, in Warwick's

work when I got a young horse.

I got, I had this six month old Norwegian

fjord pony kind of fall into my lap.

And I had never, I.

Trained a horse before, like

started a horse as a baby.

And she was really challenging.

My older mare is very easy, very,

just like a joy to work with.

And this young horse was puff like she, I

would, she was, she was just like on you

all the time, kind of like nipping and

biting and you would try to like, create

space or like, I would read different

things like use a whip to back them

up and things, and she would just like

bite the whip and try to run me over.

And like she did not hair like what I did.

And that I somehow kind of like

stumbled upon warwick's approaches.

And his really connected, I think with

with me and like what I felt was possible

for me because I just don't, I don't

have a lot of that like really like

aggressive, intense energy, I think.

And I think my, that young horse

saw that in me and was just like,

I'm just gonna run all over her.

And I think I didn't have a

really good sense of, even

Rupert Isaacson: you, you say that though,

Leanna, but I, I know you well enough to

know, I've seen you in situations where it

is true, you don't get aggressive, but you

do very clearly express your boundaries.

If you're a horse nerd, and if you're on

this podcast, I'm guessing you are, then

you've probably also always wondered a

little bit about the old master system.

of dressage training.

If you go and check out our Helios Harmony

program, we outline there step by step

exactly how to train your horse from

the ground to become the dressage horse

of your dreams in a way that absolutely

serves the physical, mental and emotional

well being of the horse and the rider.

Intrigued?

Like to know more?